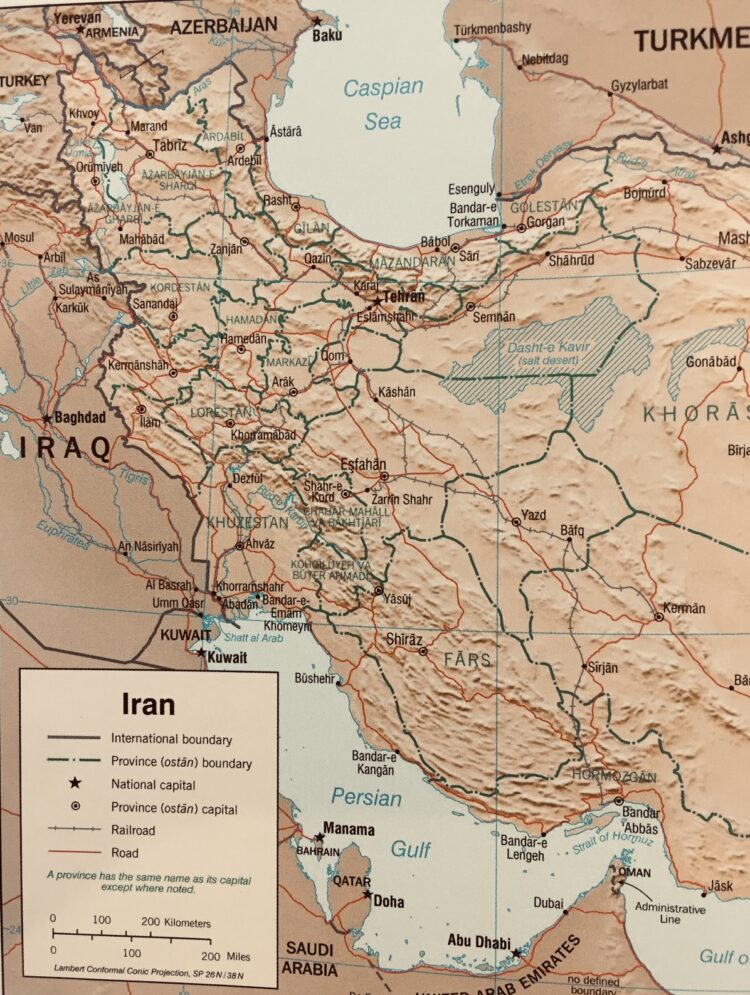

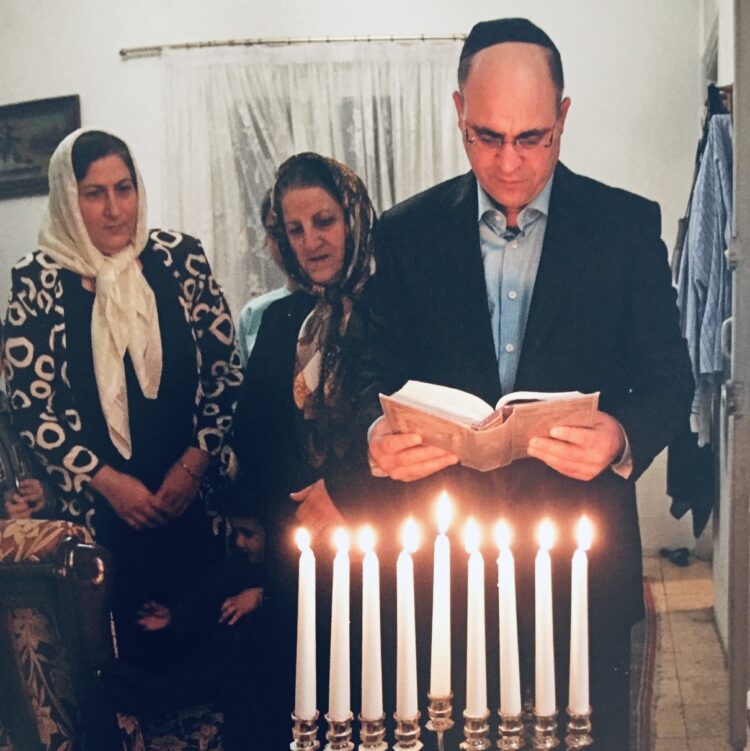

Iranian photographer Hassan Sarbakhshian spent two years travelling around Iran documenting its Jewish community, the largest in the Middle East outside Israel. He joined Jews at family gatherings, during holidays and at their workplaces, providing a rare glimpse of an ancient community whose origins can be traced back to the Babylonian exile 2,700 years ago.

His animated images appear in Jews of Iran: A Photographic Chronicle, published by Pennsylvania State University Press.

The text is furnished by Parvaneh Vahidmanesh, an Iranian journalist currently working at Radio Free Europe’s Persian service, and Lior B. Sternfeld, an associate professor of history and Jewish Studies at Pennsylvania State University and the author of Between Iran and Zion: Jewish Histories of Twentieth Century Iran.

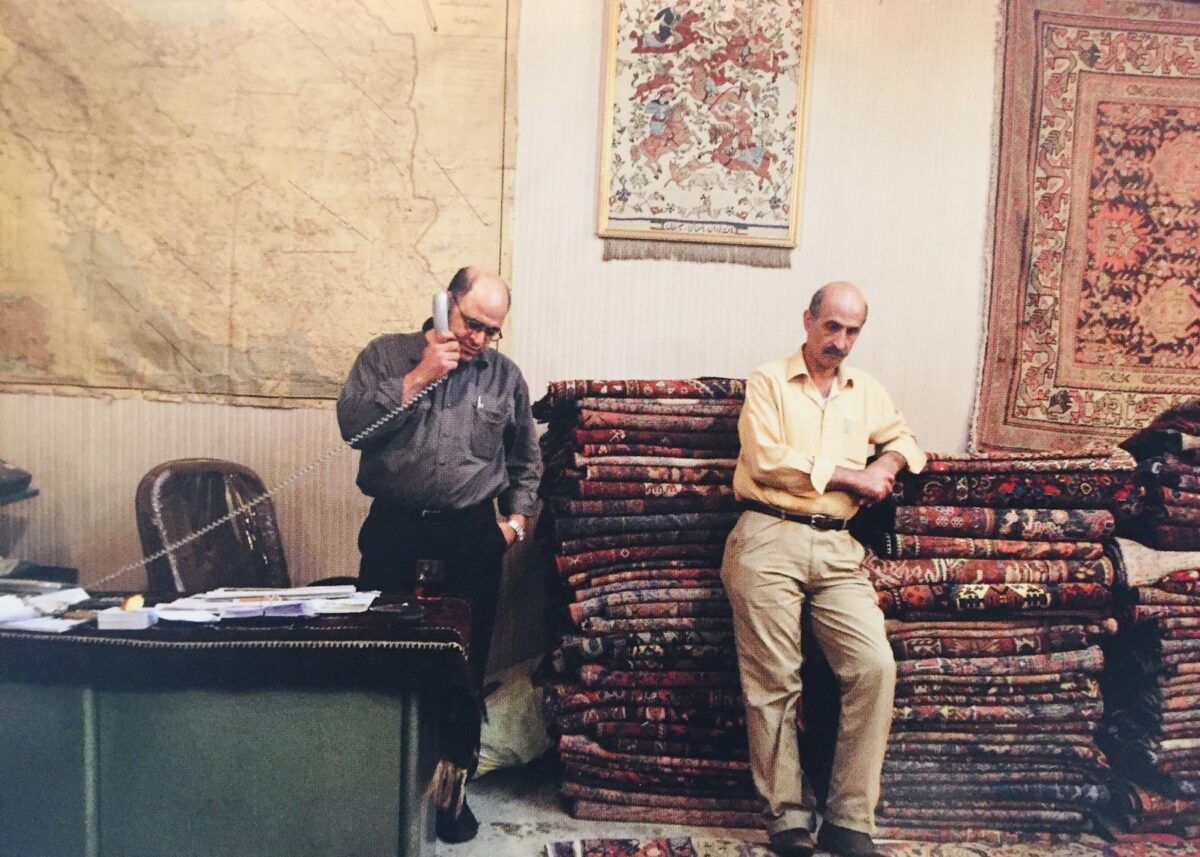

The eclectic photographs in this attractive coffee-table volume run the gamut from two Jewish carpet merchants working in their shop in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar to a group of Jewish boys playing football at a Hebrew school.

Still other photos illuminate the diversity of Jewish life in contemporary Iran.

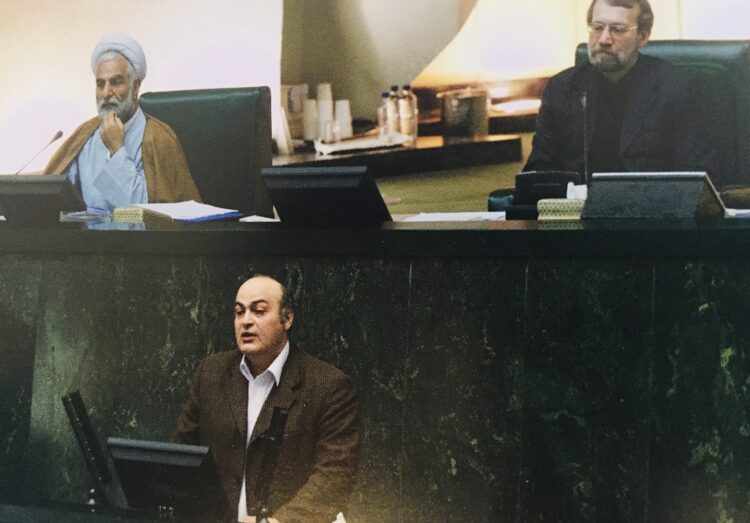

Samak Moreh Sedegh, the Jewish parliamentary representative, addresses the Islamic Consultative Assembly.

The former president of Iran, Mohammad Khatami, visits a synagogue in Tehran.

A group of Jewish students carry an anti-Israel placard at a demonstration.

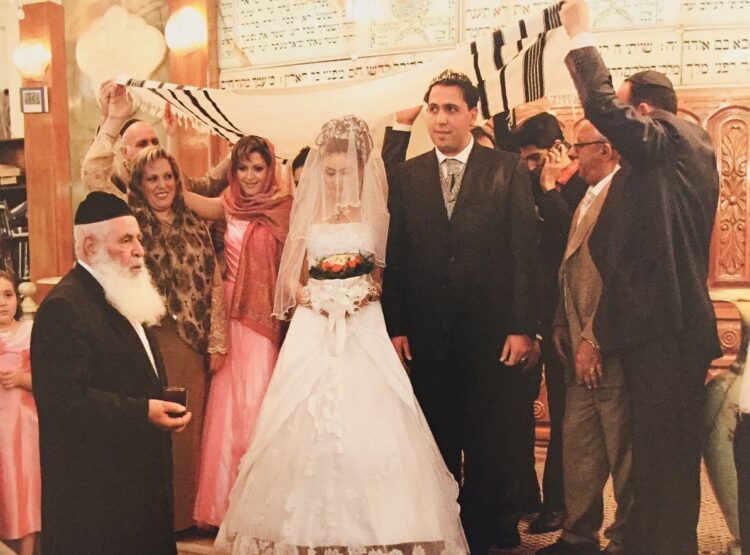

A newly married bride and groom stand under a chuppah. Jewish males pray in a synagogue.

A Jewish physician visits newborn Muslim babies at the Dr. Sapir Hospital and Charity Center, which is owned by the Jewish community.

By any measure, the photographs are innocuous and certainly uncontroversial, yet the book in which they appear was regarded as subversive by the Iranian government.

When Sarbakhshian delivered the manuscript to Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance for permission to have it published in Iran, the Ministry of Intelligence accused him of “producing propaganda for Judaism.”

In short order, he lost his press card and was forced to leave Iran. “A book we could have published in Iran was never published and remained in a dark room of Iran’s censorship system,” he writes.

Vahidmanesh, whose Jewish family was compelled to convert to Islam around 1900, elaborates. She and Sarbakhshian, whom she met in 2007, finished the volume in mid-2008, only to learn that the authorities considered it Israeli propaganda. “We would never be able to publish the book in Iran,” she says.

In a brief essay, Sternfeld describes Iranian Jews as Iranian by nationality and Jews by religion. “Full loyalty to their country is expected, and they are often suspected of loyalty to their ancestral homeland, Israel, which is at odds with their political and chosen homeland.”

By his estimation, there were 15,000 to 20,000 Jews in Iran as of 2020, compared to a high of 100,000 in 1948. Twenty five thousand Jews, the community’s poorest, emigrated following the birth of Israel. Many more departed after the 1979 Islamic revolution, the majority settling in Los Angeles, which came to be known as Tehrangeles, and Israel.

As Sternfeld observes, Persian Jews were second-class citizens until the final years of the Qajar dynasty (1795-1925). With the ascendance of Reza Pahlavi, the new shah, the last remaining anti-Jewish restrictions were abolished and Jews were granted full civil rights, though the Zionist movement was forced to go underground.

Britain and the Soviet Union invaded Iran in 1941, partitioned it, deposed Reza Shah and installed his son, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, as the new shah. From that point onward, Jews enjoyed unprecedented equality.

The pro-Western Pahlavi monarchy was overthrown in the early months of 1979. Some Jews who had been opponents of the shah’s regime supported the upheaval.

Recognized religious minorities — Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians — were permitted to send representatives to parliament and operate their places of worship, religious schools, institutions and clubs.

The supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, distinguished between Judaism and Zionism, but given Iran’s visceral hostility to Israel, he compelled Jews to avoid even the appearance of any affinity with Israel or Zionism.

So Jews are potentially vulnerable and are obliged to support Iran’s official policies.

Examples abound: The Iranian Jewish leadership has regularly lambasted Israel and endorsed the Palestinian cause. Iran’s chief rabbi condemned the United States after its drones killed Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Force.

Last month, the Central Jewish Committee in Tehran deplored the anti-regime protests that have roiled Iran for the past three months: “The community declares that the enemies of the system are creating insecurity by targeting the unity of the people. Unfortunate events and incidents have occurred in our beloved country, which has hurt the hearts of those loyal to Iran and the holy Islamic system.”

Iranian Jews have never been in physical danger since the revolution more than four decades ago. Certainly, their synagogues and institutions have been safe from attacks, which gas not been the case in either the United States or Europe.

But since then reside in a country dedicated to Israel’s destruction, they must be exceedingly careful not to offend the powers-that-be.

They are walking on eggshells.