Janina Quint’s informative documentary, Germans & Jews, illustrates the degree to which their relations have radically improved since the Nazi era, yet remain troubled.

Seven decades after the collapse of Adolf Hitler’s racist regime, Jews in the Diaspora continue to be suspicious of Germans and often recoil when they hear German, while Germans tend to feel generally awkward around Jews. Nevertheless, Jewish life in Germany is thriving, while Berlin, the capital of Germany, has the fastest growing Jewish population in Europe.

This paradox is expertly explored by Quint in this absorbing film, which is now available on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform.

Released in 2016, during which Germany admitted some one million Muslim refugees from the Middle East, Germans & Jews is wide-ranging in scope and substance.

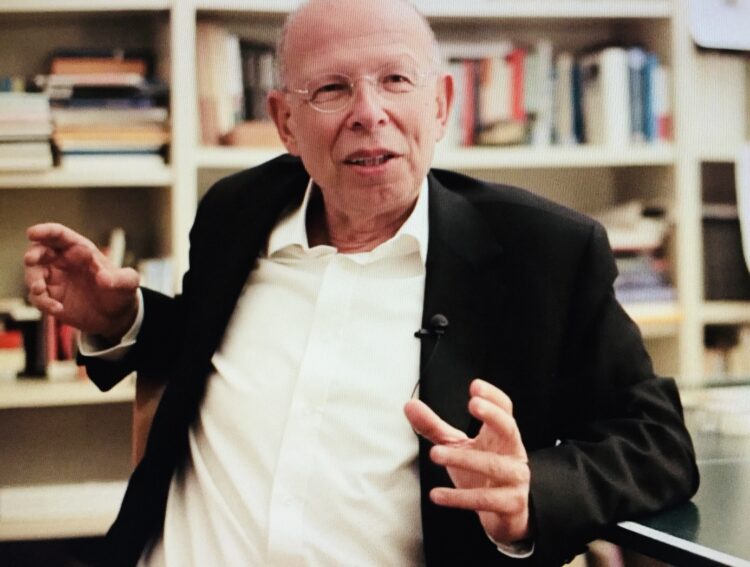

Quint interviews a diverse variety of people living inside and outside Germany, from the late distinguished historian Fritz Stern to Raphael Seligmann, the scion of German Jews who left Berlin during the Nazi interregnum and settled in Tel Aviv, only to return to Berlin after World War II.

The Seligmanns were among 27,000 Jews who immigrated to West Germany between 1945 and 1990. A much smaller proportion of Jews settled in East Germany, a communist state aligned with the Soviet Union.

Since the unification of Germany, tens of thousands of Russian Jews have poured in, dramatically raising the total number of Jews in Germany to around 200,000, or 0.2 percent of its population. According to Thorsten Wagner, a historian, the vast majority of Germans have never met a Jewish person.

On the eve of the Nazi takeover in 1933, Germany was home to approximately 525,000 Jews.

Judging by their comments, the interviewees in Quint’s film are quite conflicted.

Herbert Weber, a teacher, sometimes struggles with his German identity. Should he feel guilty? Was his grandfather, a Wehrmacht soldier killed in battle, a victim or a perpetrator?

Stern’s family on both sides converted to Christianity before the advent of Nazism, yet they were persecuted as Jews prior to their departure for the United States in 1938. “My hatred for Germans was immense,” he admits. “The Nazis made me Jewish again.”

In his view, West Germany’s decision in the early 1950s to compensate Jews for their suffering was its admission ticket back to European civilization.

Many Germans were awakened to the Holocaust by a series of events — the trial of war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Israel in the early 1960s, the “Auschwitz” trials in Frankfurt in the mid-1960s, and the 1968 student protests.

Barbara Hahn, a professor of German studies, recalls her grandmother saying that Germans would be punished for having tormented and murdered Jews.

Holocaust, an American television series released in the late 1970s, was watched by twenty million Germans and left a deep impression. Christiane von Korff, now a journalist, was shaken by it and asked her parents whether Nazi atrocities occurred.

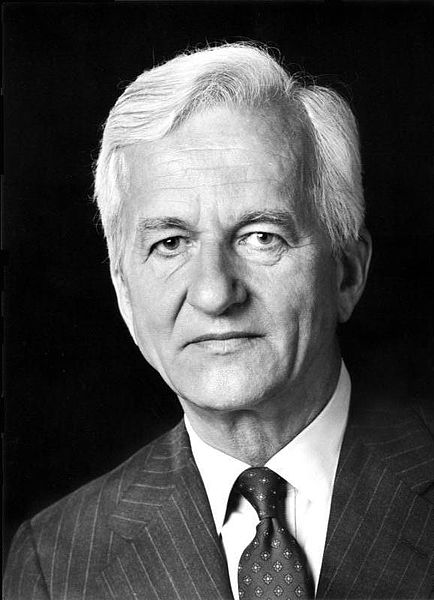

On May 8, 1985, the fortieth anniversary of the end of the war, West German President Richard von Weizsacker delivered a sobering and stunning speech on the Nazi period and Germany’s persecution of Jews. “All of us, whether guilty or not, must accept the past,” he declared. “We are all affected by its consequences and liable for it … May 8 was a day of liberation.”

Wagner, a liberal whose family ardently supported the Nazis, believes that Germany was absolutely correct to confront its Nazi past with unflinching candor. Germany has acknowledged this ugly dimension of its history by building museums and monuments, notably the Topography of Terror Museum, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews in Europe, and Track 17 in Grunewald station, all in Berlin.

And yet Jews in Germany like Ariel Cukiermann, who was born and raised in Berlin, does not define himself as a German. For decades, Jews in Germany sat on their suitcases, as the old phrase went, waiting for the day they would finally leave, he says.

The Jewish community has grown tremendously in recent years, bolstered by the arrival, in part, of Jews from Israel. Arik Hayut and Yuval Halperin, both musicians, are among the thousands of Israelis who have migrated to Berlin.

Although surveys indicate that twenty seven percent of Germans hold antisemitic views and that fifty five percent believe that the national debate on the Nazi period has been exhausted, Jews do not feel unsafe in Germany, Hayut observes.

Some Muslim newcomers have brought antisemitic stereotypes and tropes with them, but Quint does not examine this problem. Germans & Jews, nonetheless, is a fine and instructive overview of a complex issue.