Spain was supposedly a neutral power during World War II, yet the Spanish government was resolutely in Germany’s camp. In the summer of 1941, Spain dispatched a largely voluntary expeditionary force, known as the Blue Division, to fight alongside Germany in the Soviet Union.

Recruited by the Spanish army and the Fascist Party, or the Falange, the Blue Division was disbanded and replaced by the Spanish Legion of Volunteers in 1943.

A year later, hundreds of Spanish war veterans, new volunteers and civilian workers joined the Wehrmacht and Wafen-SS units, regarding their service as a continuation of the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War. Some fought to the bitter end in the ruins of Berlin in the spring of 1945.

Dozens of Spanish pilots also joined the German Air Force and a group of Spanish sailors served in the German Navy.

Altogether, 47,000 Spaniards joined the German war effort, with nearly 5,000 having been killed. Forty two thousand Spaniards returned to Spain from the battlefields and, in contrast to other Europeans who risked life and limb for the Nazi regime, they were not stigmatized as collaborators. Instead, they were treated as inconvenient heroes by General Francisco Franco’s government, which after 1945 sought to whitewash its association with Nazi Germany and align itself with the West against the Soviet Union.

Xose Nunez Seixas, a Spanish historian at the University of Santiago de Compostela, explores this intriguing topic in a superb book, The Spanish Blue Division on the Eastern Front, 1941-1945, War, Occupation, Memory, published by the University of Toronto Press.

As he points out, the Blue Division was “an uncomfortable memory” for Franco’s right-wing regime in postwar Europe and the constitutional monarchy that supplanted him after his death in 1975. Yet the Spanish armed forces and military academies still teach and idealize its “heroic deeds,” and streets, squares and monuments have been named after its fallen members.

In postwar Spain, he explains, Francoist historians regarded the Blue Division as the price Spain had to pay to combat communism, maintain its “non-belligerency” status in the war, and shield Spain from the threat of a German invasion. Anti-Franco historians argued that the Blue Division was a tangible expression of Spain’s pro-German orientation and a reflection of the values of its conservative Catholic class.

More recent research has shown that, while Franco and most of his colleagues wanted to enter the war on the Axis side, they demanded a hefty reward — the possession of French colonies in Morocco, Algeria and Cameroon. Since this territorial demand would have been totally unacceptable to Marshal Henri Philippe Petain of Vichy France, Germany’s ally, the Germans sided with Petain rather than with Franco. As a result, Franco’s only meeting with Adolf Hitler, on October 23, 1940, was seen as a failure by both sides.

During the course of the hostilities, Franco adhered to a theory of “three wars,” which divided the war into three separate conflicts. In the first, pitting Germany against the Western democracies, Spain would be neutral. In the second, between Germany and the Soviet Union, Spain would be pro-German against a common Bolshevik enemy. In the third, which pitted the United States against Japan, Spain would back the U.S. but refrain from declaring war on Japan.

According to Seixas, pragmatic German diplomats in Madrid wanted Spain to remain neutral to ensure that Spanish exports of wolfram — a strategic metal crucial in the manufacture of weapons — would not be interrupted.

Until 1943, Spain maintained its peculiar position of “non-belligerency,” but with an open preference for the Axis countries. Under intense pressure from the Allies, Spain adopted full neutrality after that date. From mid-1944 onward, when all Spanish soldiers had returned from the Eastern front with the exception of a few hundred fanatics, Spain benevolently portrayed the Blue Division as a Catholic, anti-communist initiative, devoid of sympathy for Germany and its Axis allies.

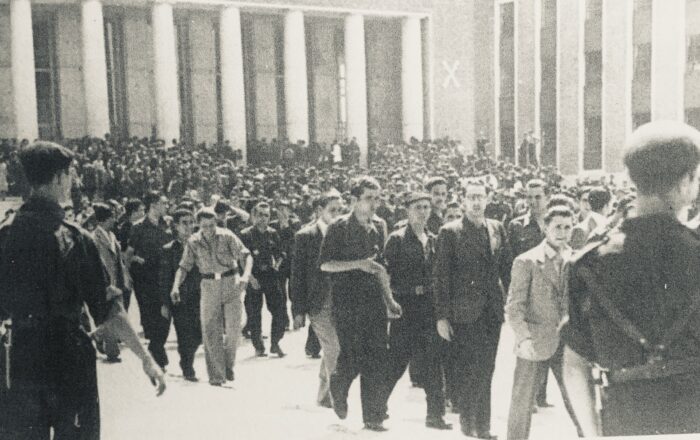

The Blue Division, an infantry unit that would be commanded by General Augustin Munoz-Grandes, was created on June 21, 1941, just hours before Germany invasion of the Soviet Union. Portrayed in purely anti-communist terms, it was popularly known in Spanish as the Division Azul. It was conceived by Foreign Minister Ramon Serrano-Suner as he dined with two Falangist leaders in Madrid. The concept was not original, since a considerable number of volunteers from a wide array of European nations had joined or would join the Wehrmacht.

A high proportion of its recruits were university students and young lawyers. The rest tended to be skilled and unskilled workers, civil servants and day laborers. Many of the volunteers shared a desire to exact vengeance for the suffering their families had endured during the Spanish Civil War. Thousands of White Russians, or anti-Bolsheviks, signed up with the Blue Division as well. Still other recruits were motivated by material incentives. In some cases, former leftists enlisted with the aim of leaving Spain.

For Falangists, the war in the Soviet Union represented an opportunity to restore Spain’s “imperial destiny” and increase its participation in the restructuring of Europe along the lines of Nazi ideology.

Although most Spanish fascists regarded the Italian model as the most appropriate for a staunchly Catholic country like Spain, they admired Adolf Hitler as the charismatic leader of a united anti-Marxist, nationalist front who had imposed his political will on his opponents. “Germany’s rebirth shone as an example for a decadent Spain … and proof of the irresistible modernity of fascism,” writes Seixas.

Falangists, too, believed they owed Germany a debt of gratitude. During the Spanish Civil War, Hitler backed Franco’s Nationalists rather than the Republicans, providing financial, diplomatic and military support. The Condor Legion, composed mainly of German pilots and ground crews, played a pivotal role in the Nationalists’ victory.

Yet Nazi antisemitism posed a dilemma for some Falangists. While they disliked Jews and supported Germany’s persecution of Jews, they did not generally subscribe to the Nazi version of racial antisemitism. In short, the aversion of Spanish fascists toward Jews was religious, not biological.

The few Jews who lived in Spain after the civil war were not deprived of their civil rights, but the authorities closed some synagogues. With the outbreak of World War II, Jewish refugees were generally allowed to pass through Spain on condition that they left as soon as possible.

The German ambassador in Madrid, Bernhard von Stohrer, reported in 1941 that the Jewish question in Spain was not a problem since the majority of Jews had converted to Christianity long ago.

In Budapest, the Spanish diplomat Angel Sanz-Briz distributed Spanish passports to dozens of Hungarian Jews, thereby saving their lives. He informed the Spanish Foreign Ministry that Jews were being deported and murdered, but it was not until the spring of 1945 that censors permitted the Spanish press to publish stories about the Holocaust.

Seixas argues that Nazi influence among Falangists and monarchists reached its highest point between 1937 and 1942, when Germany and Spain signed a series of political, economic and cultural agreements. “For the Germans, the relationship was a strategic one. Hitler and his ministers hoped to include Spain in the economic frame of the New European Order under German guidance.”

During this era, intellectual exchanges multiplied, Spanish academics converged on German universities, and Germany raaised its influence in Spain by subsidizing daily newspapers and radio stations and distributing leaflets presenting Hitler as a modern Christian knight who protected European civilization from Bolshevik hordes.

Yet, as Seixas observes, Falangists were shocked by Germany’s non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union and disapproved of its invasion of Poland. These reservations vanished after Germany’s conquest of France, a historic enemy of Spain, and its invasion of the Soviet Union.

The Blue Division was activated in July 1941, just weeks after German armies crossed the Soviet border. It was deployed to cover German defensive positions and used in partisan warfare. Yet German officers were openly disdainful of Spanish military culture, says Seixas. “They saw in their Spanish colleagues a blend of social elitism, professional ignorance and laziness.” Hitler, however, appreciated Spanish soldiers, perceiving them as undisciplined but reliable.

Spanish troops battled a punishing climate, coping with extreme cold and frostbite in winter, rivers of mud in spring, suffocating temperatures and mosquitos in summer, and ubiquitous lice during all seasons.

As they marched through eastern Poland en route to the Eastern front, or passed through the Baltic cities of Vilnius and Riga, they encountered Jews, whom they associated with communism. And while they displayed generic cultural and religious animus toward Jews, they refrained from embracing biological racism. Seixas claims that most soldiers in the Blue Division had no knowledge of the Holocaust, whose pace and severity accelerated following the Wannsee conference on January 20, 1942.

Some Spaniards were offended by the methodical and impersonal cruelty of Germans toward Jews. Still others fraternized with Jewish women, prompting German General Fedor von Bock to note in his diary that Spaniards had engaged in “orgies” with them.

Seixas states categorically that Spanish troops did not participate in killings or raids against Jews, nor were they ordered to do so. “Thus, Spanish volunteers were never involved in the systematic annihilation of the Jewish population, unlike their Romanian counterparts in Bessarabia and the Ukraine.” In general, they behaved like bystanders rather than perpetrators.

“Spanish fascists did not harbor an ideology that favored systematic segregation or extermination of Jews,” he claims. “They had no clear sense of what the Jews as a collective entity actually were: a religious faith, an ethnic or cultural group, or a ‘race.” He adds, “They showed no ill will in word or action to the Jews they encountered, but traditional anti-Jewish prejudice surfaced in their diaries or later reflections.”

With the dissolution of the Blue Division in March 1944, Spaniards who wished to continue fighting in the Wehrmacht lost their Spanish citizenship. They belonged to a class of Spaniards who fervently believed that the Third Reich represented an authentic example of revolutionary fascism.

Six hundred to 1,000 Spanish volunteers joined the German army after that date, and were sent to various fronts, including Yugoslavia, Romania, and Italy. Seixas describes them as “adventurers, opportunists, (and) fascist fanatics.” Several dozen remained in Berlin until the collapse of the Third Reich.

“In the final battles of the war, some Spaniards were captured by the Soviets, others by the Americans and the British. A handful managed to flee disguised as civil workers and reached Paris, Switzerland and Rome, where they were helped by the Spanish embassies.”

Seixas displays contempt toward these diehards, branding them as “a marginal phenomenon, a band of adventurers, thieves, murderers and a few desperate war veterans unable to shift back to civilian life.”

Even before the war ended, Franco began to downplay the Blue Division, claiming its formation had been “a clever maneuver to appease Hitler while keeping Spain out of the conflict.”

Blue Division veterans reaped postwar state benefits, gaining access to civil servant jobs, free tuition at universities, senior army positions and ministerial posts. For example, Fernando Castiella, a professor of International law at Madrid University, was foreign minister from 1957 to 1969.

Blue Division memoirists, while mostly avoiding the Jewish question, distanced themselves from Nazi racism through a selective accumulation of anecdotes. But they still had no sympathy for Jews as a collective, or the new state of Israel, and shared a belief in the Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy theory.

One memoirist, Riudavets de Montes, lamented the persecution of Jews, yet he was not fond of them either. Jews were “a cursed race able to destroy the world if a favorable occasion arose,” he wrote. “They were the assassins of Jesus, the … deicidal people” and “repugnant revolutionaries” like Karl Marx.

Such was the noxious world view of Blue Division volunteers.