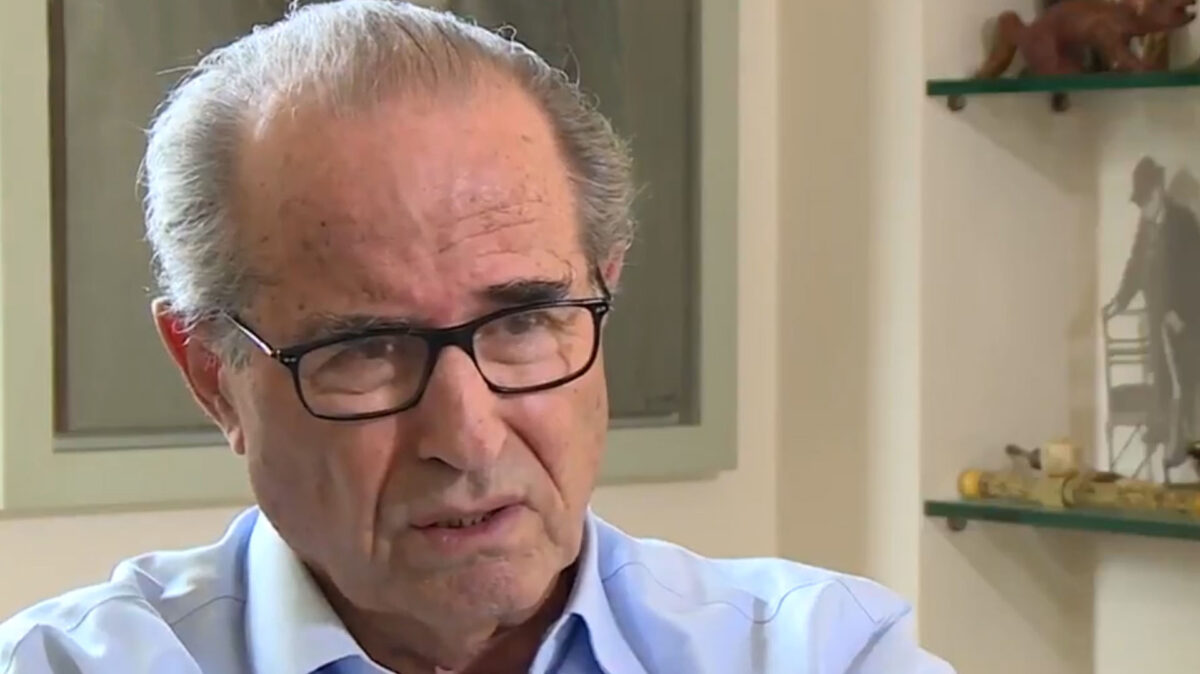

Shabtai Shavit worked for the Mossad, Israel’s vaunted external intelligence agency, for 32 years. From 1973 to 1976, he was head of operations. And in the homestretch of his career, from 1989 to 1996, he was its director.

Appointed to his post by Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, he was the first director of the Mossad who had not fought in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence.

Shavit looks back at the 1980s and 1990s in his analytical and informative memoir, Head of the Mossad: In Pursuit of a Safe and Secure Israel (University of Notre Dame Press), in which he addresses a wide array of issues and comments on Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians.

During his term of office, the world was convulsed by significant or seismic changes. One million Jews from the now-defunct Soviet Union immigrated to Israel, a development he describes as “the best thing to happen to the State of Israel since its independence in 1948.” Yitzhak Rabin returned as prime minister. Israel and the PLO signed the Oslo agreement, while Yasser Arafat established the Palestinian Authority. Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty. Benjamin Netanyahu was elected as prime minister.

Shortly after succeeding Nahum Admoni as director, Shavit told his colleagues that far-reaching changes were in the offing in the Middle East. He turned out to be right.

Iraq would become a threatening force. Non-conventional nuclear, chemical and biological weapons would be central to the Mossad’s intelligence-gathering and prevention efforts. Cyber warfare would be an issue of great concern. Iran would build up its military capabilities. Terrorism would become a global rather than a regional phenomenon, as manifested by an Al Qaeda attack on an Israeli-owned hotel in Kenya in 2002.

Shavit offers cogent analysis and vivid background information, though his prose tends to be plodding. Regrettably, but understandably, he does not delve into secret operations. And he rarely writes about himself. Example: In the early 1970s, he was posted to Kurdistan, in southwestern Iran, but he reveals very little of value.

He ventures to say, however, that Iranians consider themselves racially superior to the Semitic Muslims. As for Iran itself, Shavit believes it poses “the biggest strategic threat” to Israel, which is really old news. Iran occupies this niche for three reasons. It is ideologically hostile to Israel. Its military and economic potential cannot be underestimated. It is developing non-conventional weapons.

By Shavit’s estimate, Israel’s quest to convince its friends that Iran sought to become a “military hegemon” in the region began in 1991. Israel’s warnings were not taken seriously. “I must say that at first I was taken for a lunatic,” he writes. “Today, no serious persons carries any doubts about Iran’s intentions to develop military nuclear capability,” he adds.

By his reckoning, Israel’s military doctrine is composed of four buildings blocks — deterrence, an early warning system, absolute superiority over the enemy, and moving the war into the foe’s territory as quickly as possible. “We can see that Israel’s lack of strategic depth required it to adopt and develop an offensive defence doctrine with the exception of the option of preventive war,” he says.

He spills considerable ink in examining Israel’s attempts to forge peace with its Arab neighbors and the Palestinians.

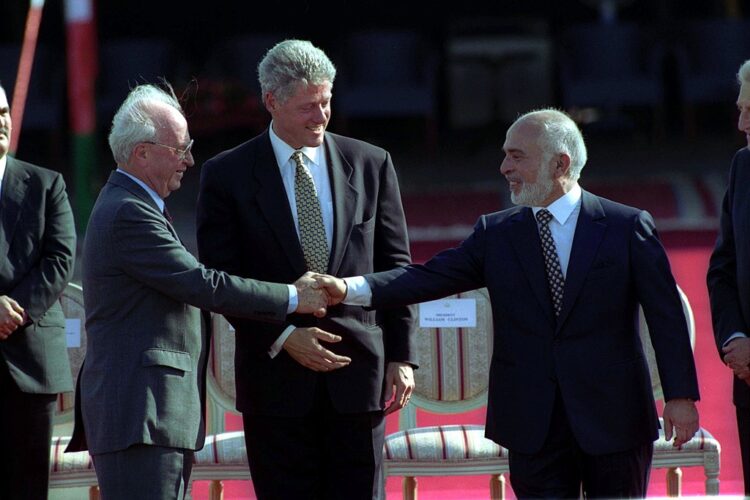

Strangely enough, he claims that the Oslo talks in 1993 were conducted by “a group of people who, in my humble opinion, were acting on behalf of themselves.” He does not elaborate, but points out that Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was skeptical that they would bear fruit. Shavit says that Rabin despised PO leader Yasser Arafat, and that he attended the Oslo signing ceremony in Washington, D.C. only because of the pressure brought to bear on him by U.S. President Bill Clinton.

Rabin was of the view that negotiations with Jordan had a very real chances of succeeding. But there was a problem, as he acknowledges. King Hussein believed that minor agreements should be reached before a full-blown peace treaty could be considered. “Rabin’s position was that there was no time for this and that it was preferable to conduct one negotiation in which the parties would bridge all gaps and reach a full peace agreement,” he notes.

In the end, King Hussein gave way and Jordan signed a historic accord with Israel. The reason is clear. He believed that relations with Israel were “valuable and essential for the survival of the kingdom.”

According to Shavit, the Mossad played a pivotal role in this process. Without revealing secrets, he admits he was “quite involved” in the diplomacy, but gives much of the credit to his deputy, Efraim Halevy, whose contribution was crucial.

In his opinion, Israel’s peace treaty with Jordan was the peak of Rabin’s “achievements” and his “greatest contribution” to peace. Shavit had a close working and personal relationship with Rabin. “I loved the man,” he says unabashedly.

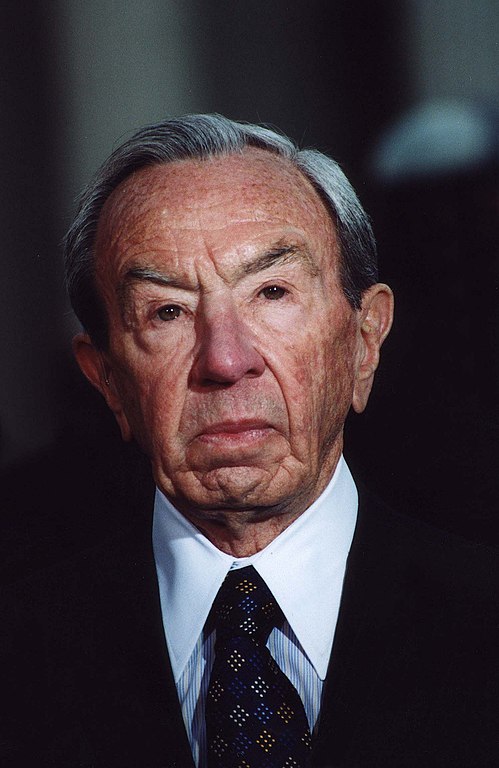

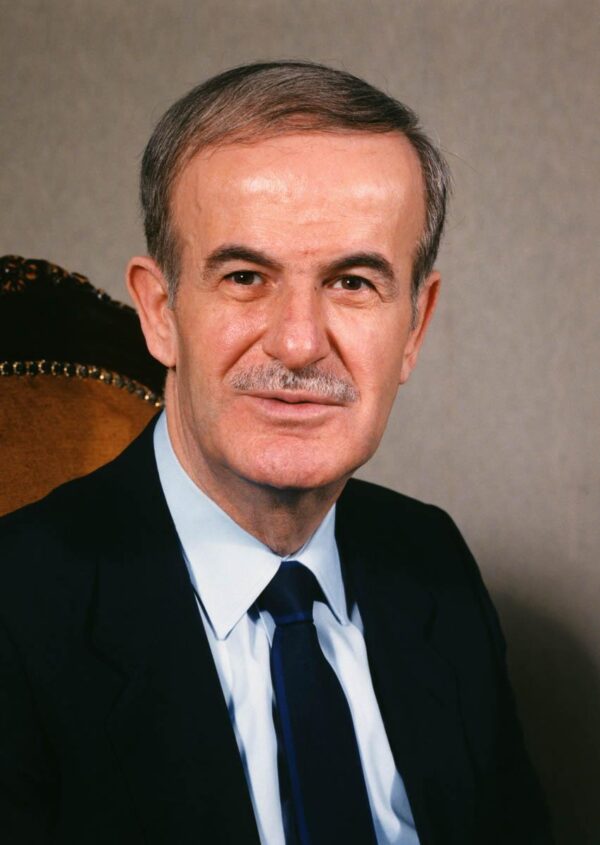

As for the Syrian diplomatic track, Shavit confirms that Rabin gave the U.S. secretary of state, Warren Christopher, a “deposit” in 1993 in which he defined Israel’s conditions for a withdrawal from the Golan Heights and peace with Syria. Syrian President Hafez al-Assad “refrained from responding substantially” to the “deposit.”

Shavit discloses that Rabin sent him to Morocco on a mission to ascertain whether Assad was really serious about peace. Shavit conferred with King Hassan II, but the answers he received “did not satisfy Rabin’s minimum conditions, and the process failed.”

To Shavit, real peace is based on three essential factors: true reconciliation, economic and social prosperity, and democratization in the Arab world.

Shavit believes that, on the Palestinian front, Israel cannot afford to renounce its sovereignty over Jerusalem or accept the demand for the “right of return.”

But if Israel is to ensure its future as a democratic Jewish state, it must “demonstrate a willingness to relinquish” its historical rights to much of the West Bank. “Even the Israeli demand to keep control of the Jordan Valley now seems to be up for negotiation,” he says.

And he goes on to say: “The dragging on of the conflict and the evasiveness of the Palestinian enemy causes harm to our national strength, our economy, and our basic democratic values … It is therefore clear that, if relinquishing territories can bring an end to the conflict, this concession must be made … giving up land in exchange for an end to the conflict is a worthwhile goal … And from a different, moral angle, there is no doubt that human life is worth more than a piece of land.”

Shavit supports the 2002 Arab League peace proposal, amended in 2007, as “an effective tool” for resolving Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians. It would, in part, require Israel to withdraw from the West Bank, acquiesce to a Palestinian state in exchange for Arab recognition of Israel, and settle the Palestinian refugee problem.

Turning to other topics, Shavit discusses the 1991 Gulf War, the turmoil in Lebanon, the Yom Kippur War, and the Mossad’s relations with the CIA.

He thinks that Israel’s decision to exercise restraint and stay out of the first Gulf War was a wise one, even though Israel was bombarded by 39 Iraqi Scud missiles. “The Gulf War brought about at least two positive strategic results for Israel: the first was that the threat against Israel from the eastern front, which entered on Iraq, disappeared. The second … symbolized the end of the pan-Arab era in the Middle East.”

Shavit expresses disappointment that Israel, following its unilateral withdrawal from southern Lebanon in May 2000, did not retaliate massively in response to Hezbollah’s aggression. “Hezbollah systematically tested … the limits of what we were willing to withstand.”

He says that Israel had no alternative but to launch a war against Hezbollah in 2006 after several of its soldiers were killed in an unprovoked border ambush. He calls that war “the first battle in our campaign against Iran,” a major ally of Hezbollah.

From his perspective, Iran and Syria have both used Hezbollah as their “long arm” to attack Israel.

Claiming that the Mossad’s contribution to Israel’s Yom Kippur War effort remains almost completely unknown, he outlines its accomplishments.

First, the Mossad informed the Israeli high command that Egypt initially intended to capture a narrow strip of land along the Suez Canal rather than advance to the Mitla Pass. Second, the Mossad provided the vital intelligence that enabled Israel to crush an Egyptian armored offensive that cost Egypt 150 to 250 tanks in a single day.

The Mossad has had cordial relations with its U.S. counterpart, the CIA, but this sense of “solidarity and intimacy” has sometimes resulted in awkward situations. “In casual conversation over a few beers, they would tell jokes with just a hint of antisemitism. When I said to them, ‘Hey guys, you’re crossing the line,’ they would answer, smiling, ‘You’re Israelis, it’s not like you’re typical Jews.'”