American- sponsored talks aimed at finally resolving Israel’s maritime border with Lebanon have been progressing relatively well since the resumption of mediation efforts by U.S. diplomat Amos Hochstein last month.

By his estimation, Lebanon has dropped its demand for part of the Karish natural gas field, which is fully claimed by Israel and is recognized by the United Nations as an Israeli asset. Israel, in turn, appears to have accepted Lebanon’s claim of sovereignty over the nearby Qana natural gas field.

With this dispute apparently having been more or less settled, Israel hopes the talks can be concluded by September, when the extraction process in the Karish zone is expected to begin. Lebanon, buffeted by a severe economic crisis and in dire need of an infusion of funds from the sale of natural gas, is reportedly eager to wind up the negotiations.

But one big, perhaps insurmountable, problem could scuttle the talks.

Hezbollah — a powerful political and military force in Lebanon closely aligned with Iran and in a state of war with Israel — seems intent on either sabotaging or gaining leverage over them.

Since the beginning of July, Hezbollah has stoked tensions between Israel and Lebanon in a bid to complicate the negotiations, which got under way last year.

On July 2, Hezbollah sent three unarmed drones toward the Karish field, all of which were shot down by Israel. A fourth drone was downed by Israel several days earlier.

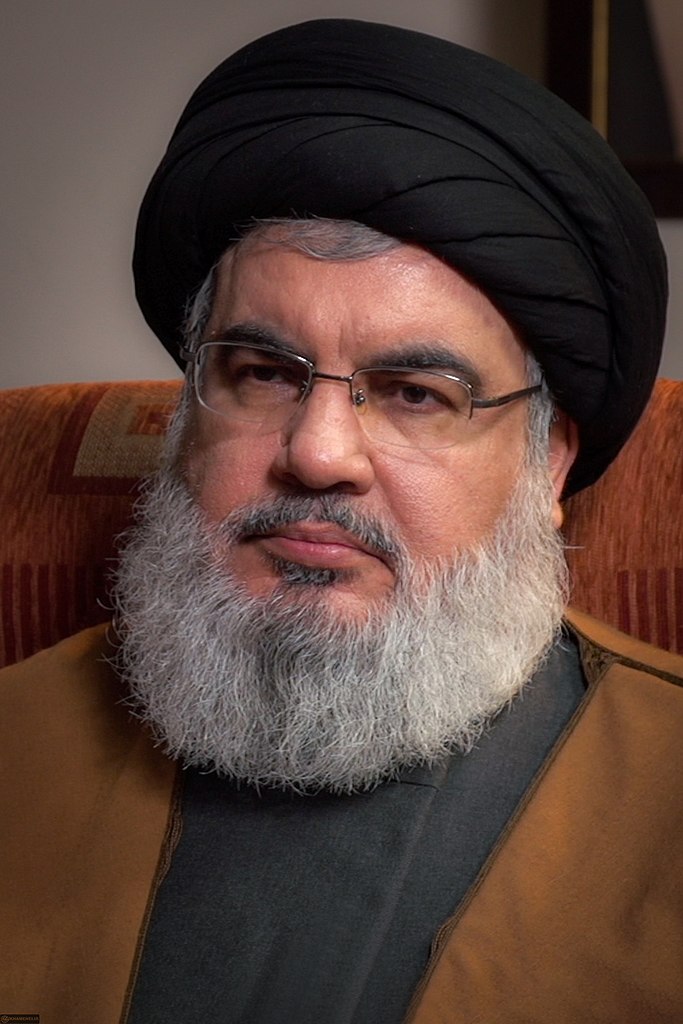

Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, heightened tensions by boasting that the drone incursions were “only the beginning.” In a speech marking the 16th anniversary of the Second Lebanon War and coinciding with U.S. President Joe Biden’s trip to the Middle East, he suggested that a war could be on the horizon. As he declared, “Write down this equation — we will reach Karish and everything beyond Karish and everything beyond that …”

Falsely inferring that Israel covets Lebanese resources, he threatened to attack Israeli natural gas platforms in the Mediterranean Sea, which, if carried out, would ignite a dangerous clash or even a war.

Nasrallah’s provocative remarks upset Lebanese Foreign Minister Abdallah Bouhabib. “Lebanon believes that any actions outside the state’s framework and diplomatic context while negotiations are taking place is unacceptable and exposes it to unnecessary risks,” he said in a sharp rebuke to Hezbollah.

Despite Bouhabib’s critique, Hezbollah on July 18 dispatched a glider that penetrated Israel’s air space. Israel shot it down, but Hezbollah’s violation of Israeli territory prompted Defence Minister Benny Gantz and Prime Minister Yair Lapid to issue stern warnings.

“Israel is prepared and ready to act against any threat,” said Lapid the following day after flying over the Karish field. “We are not heading into a confrontation, but anyone who tries to harm our sovereignty or the citizens of Israel will very quickly find out that he has made a serious mistake.”

“Israel is interested in Lebanon as a stable and prosperous neighbor that is not a platform for Hezbollah’s terror and is not an Iranian tool,” Lapid went on to say. “Hezbollah’s activities endanger Lebanon, its citizens and their well-being. We have no interest in escalation. But Hezbollah’s aggression is unacceptable and could lead the entire region to an unnecessary escalation, especially when Lebanon has a real opportunity to develop its energy resources.”

Gantz was just as emphatic. “Lebanon and its leaders are well aware that if they choose the path of fire, they will be severely burned and hurt,” he said.

These warnings have not intimidated Hezbollah, which fought a month-long war with Israel in the summer of 2006.

Within hours of their warnings, Lebanese Minister of Public Works Ali Hamieh, an ally of Hezbollah, escalated Lebanon’s war of words with Israel.

Hamieh demanded control of a 695-meter long railway tunnel running from Rosh Hanikra into Lebanese territory. The tunnel, built by Britain in 1941, was closed during the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948. Shortly after its unilateral withdrawal from southern Lebanon in May 2000, Israel blocked the tunnel’s exit with concrete. Hamieh insisted that this barrier must be demolished.

Israel has no intention of abiding by these demands, which are clearly driven by Hezbollah.

It goes without saying that Hezbollah’s rhetoric increases tension in the region and complicates Israel’s ongoing talks with Lebanon regarding a maritime border. But it remains to be seen whether Hezbollah can play the role of spoiler at a moment when Lebanon so desperately needs an economic lift.