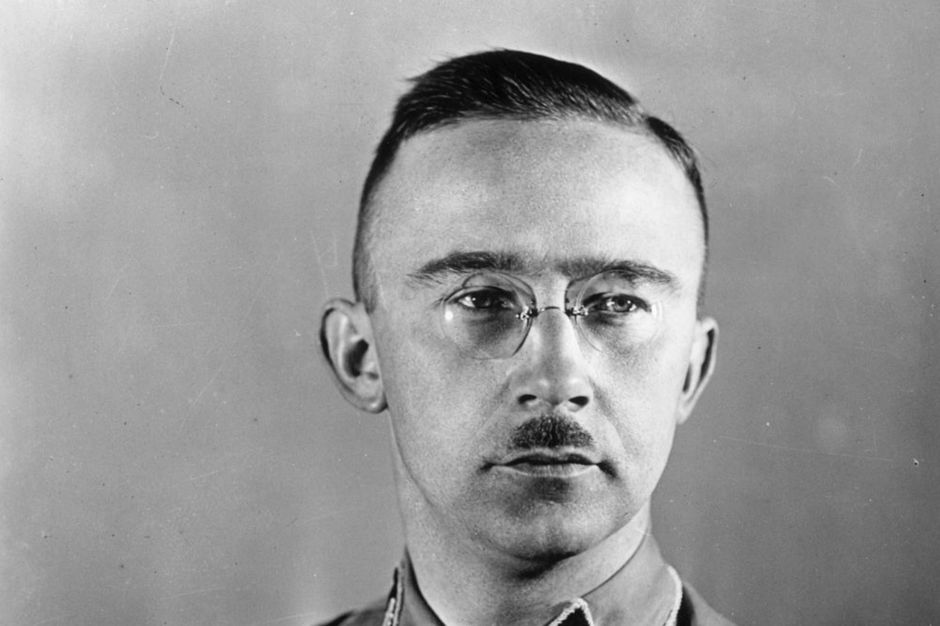

In May 1945, at the the end of World War II, American soldiers rummaging through Heinrich Himmler’s home in Gmund, Germany, found stacks of his photographs, documents, journals and personal letters. Vanessa Lapa’s chilling biopic of this mass murderer, The Decent One — which opens at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema in Toronto on Friday, Dec. 12 — is based on this invaluable treasure trove.

Himmler — the head of the SS paramilitary force and one of the architects of the Holocaust — is portrayed through his papers as an arch German nationalist, a rank antisemite, a doting father and a loving husband who fathered two children with a mistress.

Above all, Himmler comes across as mentally disturbed. Even as he carted off political opponents to concentration camps and implemented the Holocaust, he sanctimoniously regarded himself as morally pure and upright.

“In life, one must always be decent, courageous and kind-hearted,” he writes to his daughter, Gudrun, in 1941 in one of his hypocritical letters.

Lapa, a Belgium-born Israeli filmmaker, approaches her contemptuous subject in a detached manner, never losing her cool. Her modus operandi works, heightening the horror.

Actors performing voice-overs stand in for Himmler and his wife, Margarete, who was a kindred soul with respect to her attitude toward Jews. “A Jew remains a Jew,” she writes curtly. On a trip to German-occupied Poland, Margarete, a Nazi Party member, observes, “These Jewish scoundrels don’t look human.”

Which is precisely the point.

Proceeding from the assumption that “humans” (presumably racially untainted Germans) and “sub-humans” (Jews, Romas and perhaps Slavs) would be always at war, Himmler had no compunctions about resorting to mass murder. Shortly after Kristallnacht — the nation-wide pogrom in Germany in 1938 that spelled finis to its pre-war Jewish community — Himmler claims that a “master race” must be able to eliminate its foes.

Elaborating on this theme, Himmler writes Gudrun, “We will never be cruel when it’s unnecessary.” The disconnect between his philosophic pretentions and his actions on the ground are astonishing in the extreme.

The scion of lower middle-class German Catholics, Himmler was raised in a conservative milieu that glorified military values. As World War I raged, he expressed the desire to be a soldier. Later, as a member of a nationalistic fraternity, he took part in debates on the so-called Jewish question, which obsessed German racists like Himmler. In this vile spirit, he expresses disgust at finding himself in a bar “crawling with Jews.”

As his letters, journals and diaries suggest, Himmler was a Nazi at heart. Germany, he notes, must acquire territory in the east to accommodate its growing population. The Nordic race, he says, is the “royal race among mankind.”

Himmler, who joined the Nazi Party in 1923, was soon using his organizational skills to stage rallies for Adolf Hitler. And in recruiting members for the elite SS, he sought out “good and decent” men with “desired blood lines” who exuded “human kindness.”

As he rose in the ranks, Himmler remained acutely conscious of Jews, saying at one point he didn’t want to buy a particular German-made car because it was manufactured by a Jewish-owned company.

At Hitler’s behest, Himmler was placed in charge of the campaign of brutal ethnic cleansing Germany launched after its 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. But as he blithely noted, these atrocities did not disturb his sleep at night. Meanwhile, he wrote love letters to his wife and children, who missed him and hoped for his speedy return.

Himmler was in the thick of the Holocaust.

He justified the deportation of Polish Jews as a “necessary measure” and contended that the Germans had a moral right to kill them. In 1943, he ordered the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto and thanked Albert Speer, the armaments minister, for having allocated building materials to expand the Auschwitz extermination camp.

As the Allies closed in on Germany in 1944, Himmler was convinced that victory beckoned. Even as late as 1945, he was certain that Germany would win the war.

Far from being good and decent, Himmler was cruel, murderous, myopic and delusional. He was, as Lapa’s quietly powerful documentary concludes, a hard-core Nazi who had an inflated opinion of himself.

This review appeared in the Times of Israel.