Myopically enough, Hollywood failed to fully grasp the significance of the rise of Nazism in Germany, even though the American motion picture industry was largely in the hands of Jewish Americans. They underestimated the Nazis, assuming that the national socialists were a passing phenomenon, writes Thomas Doherty in Hollywood and Hitler 1933-1939, published by Columbia University Press.

Hollywood, he suggests in this absorbing book, was under the thrall of Alfred Hugenberg, a right-wing German media mogul as well as the chief stockholder in Ufa, Germany’s biggest film studio.

Hugenberg, a minister in Adolf Hitler’s first cabinet in 1933, created a sense of complacency and optimism in Hollywood by flouting the new status quo in Germany. He did not fire his Jewish employees, leading some movers and shakers to assume that Hitler would eventually restrain himself in his conduct toward Germany’s Jewish minority.

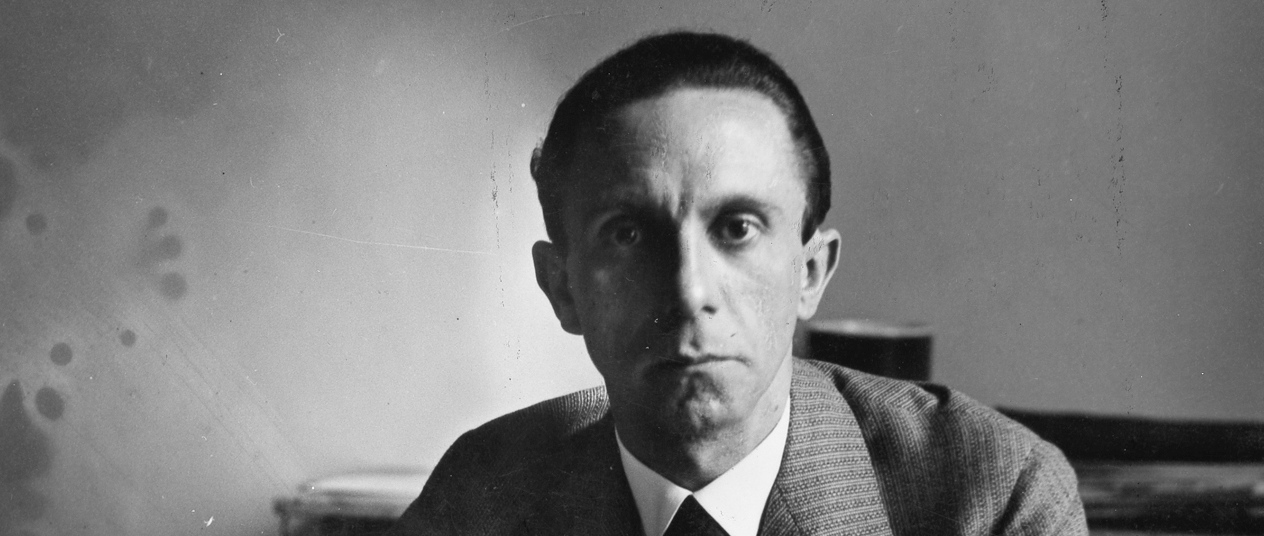

The bubble burst when Germany’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, seized control of the film industry and began dismissing Jews en masse. As part of this process, Goebbels sacked Ufa’s head of production, Erich Pommer, who settled in the United States. By then, Hugenberg had been forced out of Hitler’s government and was powerless to stop Goebbels, even if that had been his intention.

With Goebbel’s coup, Hollywood could no longer be sanguine or naive about the Nazi regime. Nonetheless, Hollywood continued doing business with Germany, going as far as submitting to its new censorship rules forbidding “cheerful” Jewish characters in films.

As a result, movies like The Cohens and the Kellys in Hollywood were not exported to Germany, Doherty notes.

However, Hollywood studios from Universal to Paramount maintained offices throughout Germany, particularly in Berlin, Dusseldorf and Frankfurt, since the German market was too lucrative to abandon. Hollywood, too, had no problem with removing Jewish representatives in Germany and replacing them with racially vetted personnel.

Warner Brothers, not willing to abide by moral cowardice, closed its German office on principle at the end of 1933, becoming the first Hollywood studio to do so. United Artists, Universal, RKO and Columbia followed suit, but Paramount, Fox and MGM hewed to the status quo.

In a further concession to Nazi sensibilities, Doherty adds, Hollywood established guidelines that amounted to appeasement. In all future movies, Germany was not to be slighted, Nazis were not to be criticized and Hitler was not to be mentioned.

“Projects about Hitler and Nazis went unmade or came to the screen so ill-made as to be dead on arrival,“ he says. Citing an example, Doherty tells of a feature film, The Mad Dog of Europe, that producers Sam Jaffe and Herman Mankiewicz attempted in vain to make.

The Mad Dog of Europe was shot down by, among others, Germany’s consul general in Los Angeles, Georg Gyssling, an avid movie buff who kept a close eye on new productions and intervened when a project displeased him.

Gyssling, though, was hardly omnipotent. Shortly after Kristallnacht, in November 1938, he accompanied renowned German director Leni Riefenstahl (Triumph of the Will) around the city, but the reception she received was chilly.

Upon her return to Europe, she complained, “I was welcomed everywhere in the United States but in Hollywood — where the film industry is controlled by Jews and anti-Nazi leagues.“

Kristallnacht jolted and angered Jack Warner and his elder brother, Harry. In the wake of this nation-wide pogrom, Warner Brothers, the first Hollywood studio to sever economic ties with Germany, initiated production on Confessions of a Nazi Spy, a domestic espionage thriller that German diplomats in the United States tried to suppress. From their point of view, the film was pernicious, “the first frontal assault on Nazism from a major studio,“ according to Doherty.

Certainly, the Jewish actor Edward G. Robinson was impressed by Confessions of a Nazi Spy, hailing Warner Brothers as “the only studio with any guts.“

Doherty agrees: “No for-profit company did more than Warner Brothers to alert Americans to what Nazism was and where it would lead.”

By contrast, MGM was callow, placing the nephew of Germany`s foreign minister on the payroll of its Berlin office and inviting German newspaper editors on a `goodwill`tour of the United States.

Despite the best efforts of some studios to curry favor with the Nazis, the number of American films allowed into Germany diminished to only 30 by 1937. Nevertheless, three studios — Fox, Paramount and MGM — maintained an unwavering commitment to the German market.

As Doherty says, Hollywood`s timidity with respect to Germany underwent a sea change between the eruption of World War II and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor two years later.

During this period, he observes, “a slate of unabashedly anti-Nazi melodramas moved through the studio pipelines, works that kindled a revived American patriotism, that called for a strong national defence, and that named Germany as the wolf at the door.“

From that point onward, Hollywood joined the anti-Nazi crusade in earnest. Suddenly, morality counted.