Ehud Olmert has the dubious distinction of having been the first Israeli prime minister to be jailed for a criminal offence. Convicted of bribery and obstruction of justice, he was released from prison in 2017 after serving 16 months of a six-year sentence.

Now 77, Olmert was named prime minister after his predecessor, Ariel Sharon, suffered a massive stroke in 2005. He remained in office until 2009, when Benjamin Netanyahu succeeded him.

Originally a right-winger in terms of his views on the Arab-Israeli conflict, Olmert moved from the Likud Party to the newly-formed centrist Kadima Party and came remarkably close to reaching a peace agreement with the Palestinians. He might have pulled it off had he not been indicted on charges of corruption and pressured to resign.

Roni Aboulafia reviews his checkered career in a substantive documentary, Honorable Men: The Rise and Fall of Ehud Olmert, which premiers on VOD platforms on April 14.

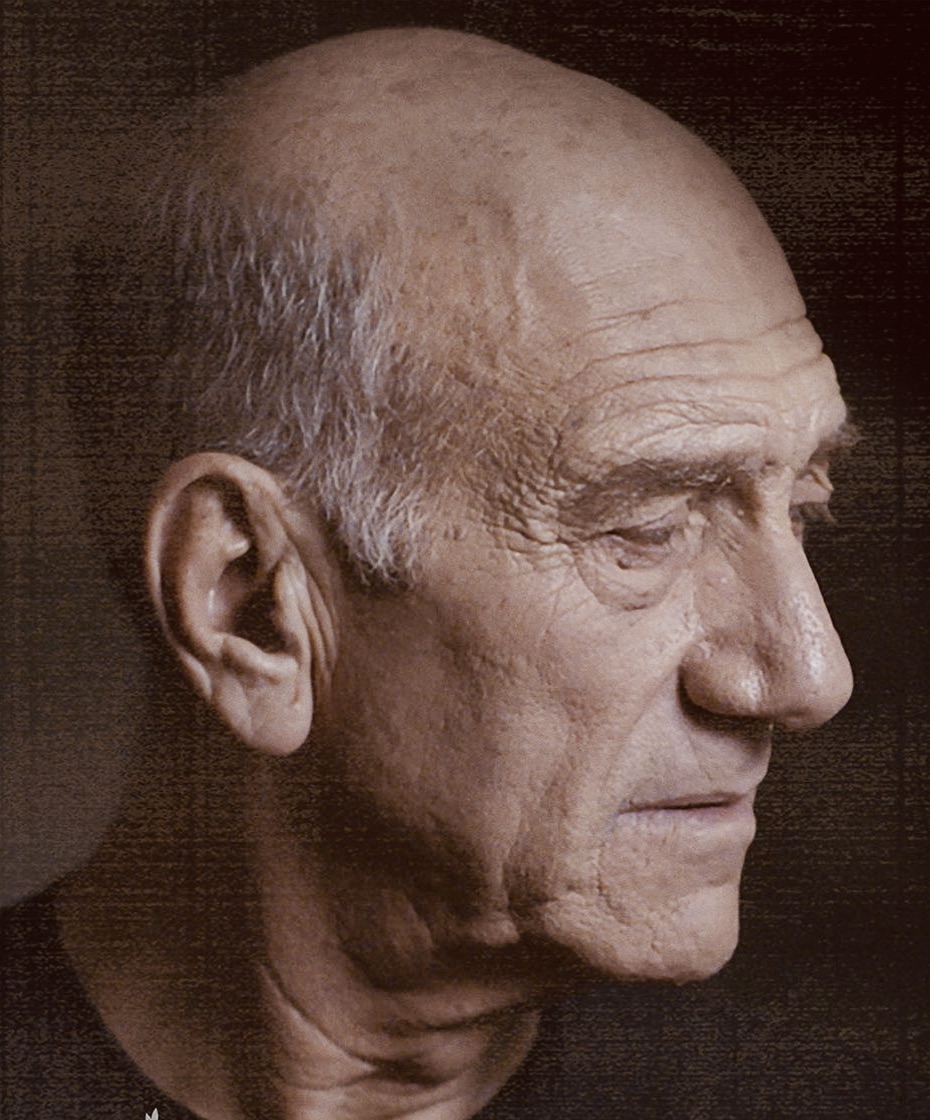

Her film starts on a somber note as Olmert, his deeply creased face gaunt and expressionless, is driven to the prison to which he has been consigned. “I accept the verdict with a heavy heart,” he murmurs. “No man is above the law.”

It is an extremely sad day for him. He realizes he will probably be remembered not for his time as mayor of Jerusalem or his tenure as Israel’s premier, but for his brush with the law and his bout in jail.

As he tells it, he was ready for the burden and the responsibility of the premiership after Sharon suddenly passed from the scene. “You’re where you’re meant to be,” he says philosophically.

At this juncture, Aboulafia winds back the clock to his youth in Binyamina, a village in central Israel where he was born, the son of Russian immigrants from the Chinese city of Harbin who settled in Palestine.

Olmert’s father, a Zionist Revisionist, was a fairly prominent figure in Menachem Begin’s Herut Party, yet he and his wife lived very modestly. “We were extremely poor,” recalls Olmert. “I wasn’t born with a silver spoon in my mouth.”

Aboulafia skims over his adolescence and mayoralty and focuses instead on his days as prime minister.

Once a champion of the settlement movement in the occupied territories, Olmert had no compunction about tearing down Amona, an illegal outpost in the West Bank, even though the demolition might cost him votes in the forthcoming general election. “It was the right thing to do,” he recalls.

Olmert won a plurality of Knesset seats in the next election, leaving the Likud, with Netanyahu as its leader, with only 12 seats.

After Sharon’s unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip in 2005 and Olmert’s subsequent decision to evacuate Amona, his ideological opponents feared he might dismantle authorized settlements in the West Bank.

Judging by his public pronouncements, Olmert was prepared to make sweeping territorial concessions to achieve a rapprochement with the Palestinian Authority. As he put it, “We are willing to compromise … to give up parts of the Land of Israel … to live in peace and harmony with the Palestinians.”

Olmert wanted to be seen as a doer who would do something big, says Elliot Abrams, an American diplomat who knew him.

At the 2007 Annapolis summit, which was organized by the United States, Olmert offered Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian Authority, concessions that none of his predecessors had ever broached. From 2007 to 2008, Olmert and Abbas met no less than 36 times, but an agreement eluded them. Strangely enough, Aboulafia omits the details of their discussions and negotiations.

Having concluded that Olmert posed a clear and present threat to Israel’s settlement project in the West Bank, his foes decided to undermine him by irregular means. They organized a nation-wide campaign to draw attention to the “irregularities” that occurred when he was the mayor of Jerusalem and the minister of industry. In short order, they amassed enough incriminating material to link Olmert to four scandals.

At this point, Aboulafia abruptly jumps to the 2006 war in Lebanon, which began after a violent incident along the Lebanese border during which Hezbollah attacked an Israeli army patrol and kidnapped two soldiers.

She is critical of the performance of the Israeli armed forces, which failed to stop Hezbollah’s bombardments of the Galilee. Taking the blame for its deficiencies, Olmert admitted he was an unpopular leader. On the other hand, she notes, Israel has managed to deter Hezbollah. Since then, Hezbollah has not attempted to ignite a war with Israel.

Aboulafia neglects to mention another aspect of Olmert’s premiership — his decision to bomb Syria’s North Korean-built nuclear reactor in 2007 — and devotes the rest of her film to his legal woes.

In 2008, he tendered his resignation after being indicted on charges of corruption, but remained on the job until Netanyahu cobbled together a coalition government in the following year.

Aboulafia examines the minutae of his legal travails, giving prosecutors, defence attorneys and Olmert’s secretary, Shula Zaken, a platform to air their diverse opinions.

To this day, Olmert denies he accepted bribes in exchange for political favors. That’s very debatable, of course. But what is undisputably true is that his quest for peace was thwarted and his reputation was inalterably tarnished by his conviction as a criminal offender.