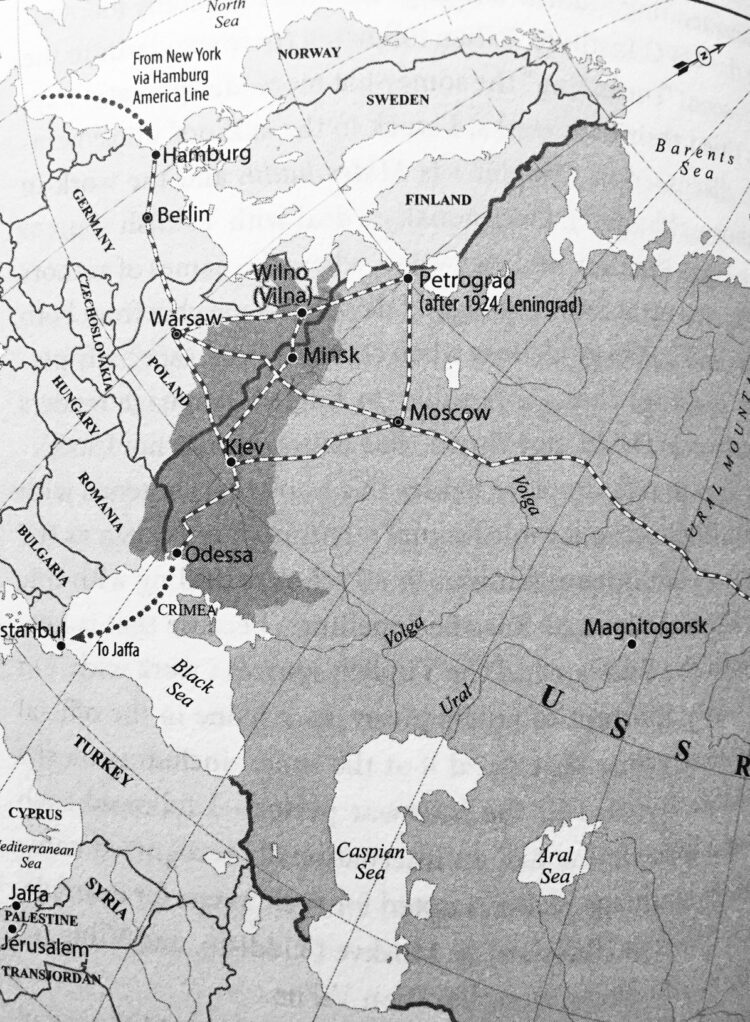

From the end of the 18th century to the second decade of the 20th century, virtually every Jewish person in the Russian empire was required by law to live in the Pale of Settlement, a vast region comprised of modern-day Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Latvia and Lithuania. Starting in the 19th century, liberalization set in as a small number of Jewish professionals and merchants were permitted to reside in cities outside it.

Pogroms from the 1880s onward prompted two million Jews to emigrate from the Pale of Settlement, leaving more than three million Jews inside it when the antisemitic Romanov dynasty fell in 1917.

Alexander Kerensky’s post-monarchist provisional government abolished the Pale of Settlement as an antisemitic anachronism. Vladimir Lenin’s subsequent seizure of power in the Bolshevik Revolution unleashed an unprecedented wave of Jewish mobility that emboldened ordinary Russian Jews to go abroad or to move to cities such as Moscow, Kharkov and St. Petersburg, which had previously been off-bounds to them. By 1939, 1.5 million Jews lived in cities and towns outside the boundaries of the former Pale of Settlement.

For these Jews, many of whom were from shtetls, revolutionary Russia meant tolerance, freedom and modernity. Yet, as Sasha Senderovich observes in How The Soviet Jew Was Made (Harvard University Press), this demographic upheaval also exerted pressure on them to discard their old ways, a process which could be difficult.

Senderovich, an assistant professor of Slavic languages and literature at the University of Washington in Seattle, explores this ambivalence through thoughtful readings of Russian and Yiddish literature, reportage and movies from 1917 to the late 1930s.

During these years, the so-called “fifth line” in Soviet internal passports played no role in marking and defining Jews. This provision was only introduced in 1932 as part of Joseph Stalin’s agricultural collectivization campaign. And it was not until 1938 that the state security organization required passport holders to declare a nationality corresponding with the ethnic origins of one of their parents.

This edict was not focused on Jews, but rather on ethnic Germans and Poles amid fears that Germany or Poland might attack the Soviet Union, writes Senderovich.

He begins his inquiry with David Bergelson, whose novel, Judgment, was published in 1929. Written in Yiddish in Berlin in the mid-1920s, it turned on counter-revolutionaries plotting an uprising against Bolshevik rule. The first six chapters were serialized in Yiddish periodicals in Poland and the completed novel came out in book form in the Soviet Union.

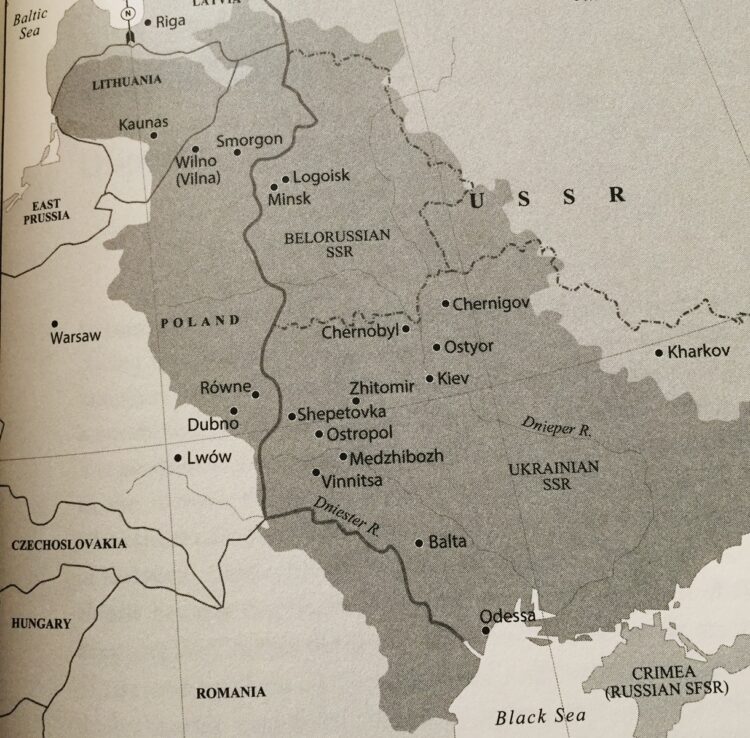

As Senderovich notes, the Soviet Jew in his novel was profoundly shaped by the lingering threat of new violence against Jews. Between 1917 and the consolidation of Soviet power in 1921, tens of thousands of Jews were murdered in a succession of pogroms in the Soviet Union’s western borderlands, particularly in Ukrainian lands.

Moyshe Kulbak’s Yiddish-language novel, The Zelmenyaners, centering on Jews from the Pale of Settlement who were becoming Soviet patriots, was published in installments in Minsk at the beginning of Stalin’s reign. Yiddish, along with Russian, Belorussian and Polish, was one of four official languages in Soviet Belorussia at that time.

“The belief that a Jew could, in theory, become a Soviet person was seemingly affirmed by the emergence of deracinated, highly educated, and mobile Jews” who could be described as “the most successful product of the Soviet system,” says Senderovich. “But this small cadre of ethnically Jewish elites, many of whom ascended to the highest echelons of the Bolshevik state, were vastly outnumbered by the much broader and more diverse population of proste yidn, simple Jews … who, collectively and individually, constituted the figure of the Soviet Jew. The new cultural constellation of the Soviet Jew, as distinct from Jewish elites in the Soviet system, was born from a much more ambivalent engagement with revolutionary changes.”

In Jews in the Taiga, a collection of literary sketches about the Far Eastern region of the Soviet Union, Viktor Fink wrote about Birobidzhan, the Jewish autonomous area near the Chinese border which had been established to render Jews more like other territorially-grounded groups in the country. “After the failure of earlier attempts to establish Jewish agricultural colonies in Ukraine, Belorussia and Crimea, the Soviet government set its sights on the Far East,” says Senderovich.

Sparsely populated by, among others, ethnic Koreans and Chinese, Birobidzhan was presented as a kind of new Promised Land for Jews.”On arrival in Birobidzhan, the shtetl Jew was to undergo a transformation into a variant of the New Soviet Man,” a healthy, muscular type promoted by the state.

Semyon Gekht’s novel, A Ship Sails From Jaffa And Back, fastened on this theme as well as it traced the journey of a Jewish man from Odessa to Birobidzhan and juxtaposed the apparent success of the Birobidzhan scheme with the problematic Zionist project in Palestine.

In keeping with Soviet tropes, Gekht presented Jews in British Mandate Palestine as agents of European colonialism. When anti-Zionist and anti-British riots shook Palestine in 1929, the Soviet regime saw them as a sign of a brewing anti-imperialist revolt by the Palestinian Arabs.

Isaac Babel, the author of Odessa Tales and Red Cavalry, published a short story in a Petrograd daily in 1918 about Hershele Ostropoler, a trickster from Yiddish folklore. As Senderovich says, the two decades following the 1917 revolution were the only time when Yiddish folklore influenced Soviet culture.

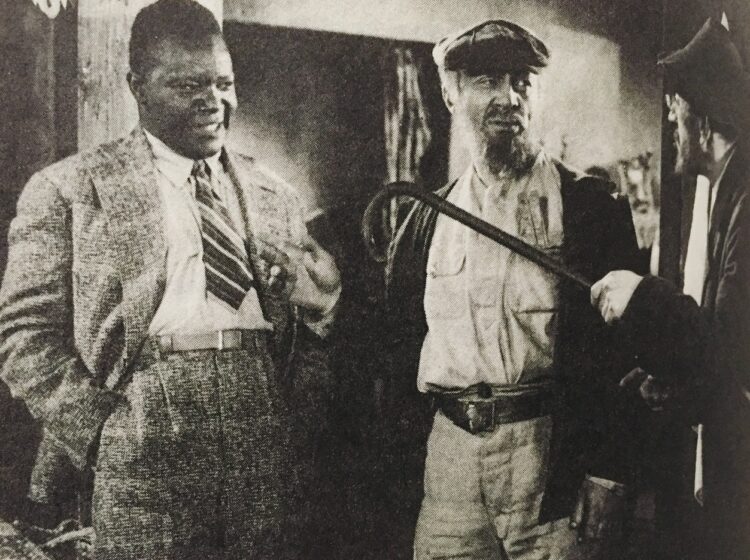

Senderovich, in his analysis of films, examines The Return of Neitan Bekker, a Socialist Realist movie directed by Rashel Milman. Thought to be the first Soviet sound film in Yiddish, it lionized the New Soviet Man. Released in 1932, with a screenplay written by the Yiddish poet Peretz Markish, it starred the famous Yiddish actor Solomon Mikhoels.

Another film, Seekers of Happiness, directed by Vladimir Korsh-Sablin, was released in 1936. It was about a Jewish family from the Pale of Settlement that settles in Birobidzhan after a sojourn in Palestine. “Working through the cultural stereotype of the unproductive Jew, the film offers a memorable portrait of Pinya Kopman, an old-world shtetl dweller (who) fails to become a productive member of Soviet society following his return.”

A shift in Soviet domestic politics, brought about by the Cold War after 1945, altered the image of Jews in the Soviet Union. As Senderovich puts it, “The Soviet Jew came into being within an idiosyncratic and culturally rich response to the Soviet state’s attempts to reform Jews, like other non-Russian ethnic groups, into model Soviet citizens. After the war, in contrast, Jews started to be seen as a fifth column undermining the state from within.”

Amid the stifling new climate, the state-sanctioned Jewish Antifascist Committee was disbanded, Mikhoels was murdered, Bergelson and Markish were executed, Gekht was arrested and exiled to a gulag, and, in an antisemitic campaign orchestrated by Stalin, Jews were branded as “rootless cosmopolitans.”

“In many ways, the tragic fate of these notable Jewish cultural figures at the end of Stalin’s reign came to be associated with the Soviet Jewish experience writ large,” says Senderovich in a stinging indictment of the New Soviet Jewish Man.