Israel’s complex and protracted conflict with the Palestinians often seems like a stubborn political and armed struggle defying resolution. Indeed, it may well continue to fester and explode for decades to come.

Tangled Roots, a six-part Israeli television series now available on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform, delves into this messy imbroglio with honestly, clarity and comprehensiveness. Anyone even vaguely interested in its origins and dynamics will learn much of value from Tangled Roots, a balanced production by Anat Seltzer and Modi Bar-On.

These episodes take a viewer back to the 19th century, when Palestine was an Ottoman colonial domain in which Jews comprised only six percent of its inhabitants but represented about 50 percent of Jerusalem’s population.

Jews and Palestinian Arabs coexisted during this era. But the arrival of masses of Jews following the Russian pogroms of the 1880s, plus the formation of the modern Zionist movement in the 1890s, placed the Palestinians on notice that the status quo was crumbling and that a new reality would replace it.

Such was the Palestinians’ concern that the Arab mayor of Jerusalem wrote an impassioned letter to Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, pleading with him to send Jewish settlers anywhere but Palestine. Herzl, an idealist, was convinced that Jewish settlement in Palestine would benefit both Jews and Arabs. Nor did he understand that most Palestinians considered themselves a distinctive group within the broader family of Arabs.

The Palestinians’ apprehension turned into outright fear when they realized that Zionists sought to build a full-fledged Jewish state in Palestine at their expense.

These incremental developments are explained in sober and methodical fashion by a procession of Israeli Jewish and Israeli Arab historians.

The outbreak of World War I, during which the Ottoman Empire sided with Germany, was a seminal period in the Middle East. Britain and France, in the secret 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement, carved up regional spheres of influence that established the future borders of Syria, Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq. And in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, the British foreign secretary agreed to the creation of a Jewish national homeland in Palestine, provided the rights of the Palestinians were not violated.

Political and religious passions flared after Britain was granted a League of Nations mandate in Palestine in 1922. Palestinian suspicions were aroused by the fact that its first high commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel, was Jewish. By then, Palestine was populated by approximately 700,000 Arabs and 85,000 Jews.

Fearing they would be dispossessed by the Zionist project, the Palestinians, who aspired to statehood, laid out their basic demands to the British: no Jewish immigration to Palestine and no land sales to Jews.

Amid the rising tension, the Zionist movement continued to purchase land, notably in the Jezreel and Hefer valleys, and to expand Tel Aviv, the first all-Jewish city.

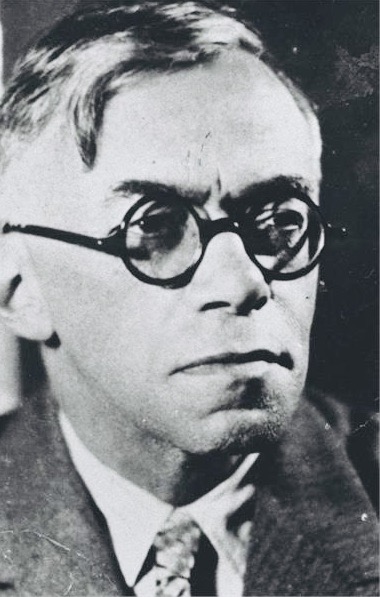

The leader of the Zionist Revisionist movement, Vladimir Jabotinsky, recognized that the Palestinians regarded themselves as a nation and warned his followers that Jewish interests could only be defended by force of arms.

Toward the close of the 1920s, the Western Wall and the Temple Mount in Jerusalem morphed into flashpoints. And in Hebron, the Jewish community was driven out after an Arab pogrom.

The Palestinians’ supreme leader, Haj Amin al-Husseini, the grand mufti of Jerusalem, was a hardliner who rejected compromise. But even moderate Palestinians like Musa Alami could not bear the notion of Jewish statehood in Palestine.

Throughout the 1930s, Jewish immigration increased to the point where Jews comprised one-third of Palestine’s population. Far better organized than the Arabs, Jews crafted what amounted to a state-within-a-state in Palestine, further upsetting the Palestinians, who, in 1936, initiated a general strike and a rebellion. Their revolt, ruthlessly crushed by British troops at a cost of some 3,000 Palestinians, prompted Britain to issue a white paper in favor of partitioning Palestine into Jewish and Arab enclaves.

In 1939, the British government issued another white paper. Much to the chagrin of Zionists, it restricted Jewish immigration and land purchases. Haj Amin al-Husseini, now in exile in Iraq, dismissed the plan and aligned himself with fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. In 1941, he would meet Adolf Hitler in Berlin.

Forty thousand Palestinian Jews enlisted in the British armed forces during World War II, when Germany’s Africa Korps almost broke through British lines to advance into Palestine. The death of six million Jews in the Holocaust was an enormous blow to the Zionist movement, which had counted on European Jewish communities to supplement Palestine’s Jewish population.

From the mid-194os onward, right-wing Jewish militias attacked British troops and officials and engaged in terrorism, blowing up a section of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem in 1946. All the while, Arab bands killed Jews.

The United Nations’ 1947 partition plan awarded 55 percent of Palestine to Jews, outraged the Palestinians, and sparked a civil war in Palestine. During this phase, the Arab League declined to help the Palestinians militarily.

Although Arabs outnumbered Jews, the Palestinians could only field 5,000 fighters, compared with 24,000 for the Jewish side.

As chaos and violence engulfed the country, Arab civilians in Haifa fled, Arab oil refinery workers in Haifa murdered their Jewish co-workers, Palestinians besieged Jerusalem, a right-wing Jewish militia slaughtered 110 Arab civilians in the Deir Yassin massacre, Arabs ambushed a Jewish convoy in Jerusalem en route to Mount Scopus, killing all its occupants, and all but 2,000 Arabs in Jaffa fled for their lives.

With Britain’s withdrawal from Palestine, David Ben-Gurion declared Jewish statehood on May 14, 1948, triggering an invasion by five Arab armies. The broad objective of the Arab states was to preserve the ethnic Arab complexion of Palestine.

Although Israeli forces managed to repel the Arab invaders, the Arabs captured 20 Jewish settlements, as well as the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Israel expelled Palestinians in Lod and Ramle. And in the hope of creating a homogeneous and more defensible state, Israel expanded its borders in the north and the south. As a matter of policy, Israel refused to allow Palestinian refugees the right to return to their homes and properties. After the war, Israel bulldozed several hundred empty Arab villages. Nazareth was the only Arab town whose residents were not subjected to expulsion.

All in all, 750,000 Palestinians voluntarily fled or were compelled to flee, leaving 160,000 Palestinians inside Israel after the end of hostilities. They were granted Israeli citizenship, but placed under martial law until 1966.

Israel expropriated 97 percent of Arab-owned lands and captured 78 percent of Palestine. These figures do not apply to Jordan, which had been part of Palestine until the early 1920s.

The upheaval affected Jews in Arab countries. After 1948, 800,000 Jews in the Arab world emigrated, either voluntarily or under duress.

As Tangled Roots suggests, the fallout from the tumultuous events of the past century and a half is still with us. As Israel prepares to mark its 75th anniversary, the Palestinians are still seeking redress and sovereignty in their own state.

As the old adage goes, the more things change, the more they remain the same.