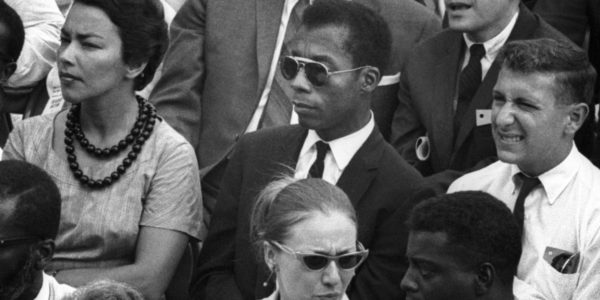

Raoul Peck’s documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, is a meditation on race in the United States, a topic unlikely to grow stale or irrelevant due its resonance in American history. Scheduled to open in Canadian theatres on February 24th, Peck’s thoughtful film is framed by the observations of the late African American novelist and essayist James Baldwin (1924-1987), who immersed himself in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

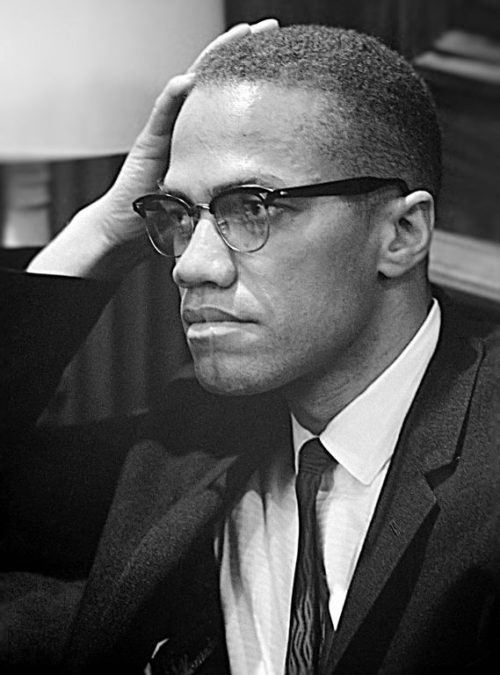

In 1979, Baldwin informed his literary agent he intended to write a book about three close friends who had played a pivotal role in it — Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers and Malcolm X, all of whom were gunned down by assassins before the age of 40. Baldwin completed only 30 pages of his proposed work, Remember This House, but after his death Peck gained access to the unfinished manuscript, which forms the core of I Am Not Your Negro.

Born in the black neighbourhood of Harlem, Baldwin left the United States in 1948 and settled in France. Like African Americans of his generation, he was up against it. Racism was rampant and segregation was the norm, particularly in the southern states. An intelligent and cultured man like Baldwin stood little chance of “making” it in his native land. Nonetheless, he returned to the United States, having missed his siblings and mother, as well as the music and food he had been raised to love.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Baldwin did not hate white people. The school teacher who had introduced him to the pleasures of reading, thereby changing his life, had been a white, and Baldwin never forgot this debt of gratitude.

Yet Baldwin harbored no illusions about the darker side of American society. Baldwin’s pithy observations about the injustices he and other blacks endured are articulated by the actor Samuel J. Jackson. The movie is rounded off by graphic archival photographs and revealing clips from newsreels and Hollywood films. An old FBI report claiming that Baldwin was a “dangerous individual” who might be a security threat is also weaved into the film’s fabric.

Portraying himself as a “witness” on a truth-telling journey, Baldwin speaks his mind candidly. Taking aim at well-meaning whites who talked themselves into believing that Birmingham, Alabama — a flashpoint of the civil rights movement — was on Mars rather than in the United States, he accuses white Americans of apathy and ignorance with respect to the manner in which they related to the black community. At another point, he claims that America does not know what to do with its black minority.

Zeroing in on the hypocrisy that plagues America, Baldwin observes that when a black man demands liberty, he’s treated like a criminal. “This is not the land of the free,” he concludes. But in a remarkably prescient comment, Bobby Kennedy, the then U.S. attorney-general, claims there is no reason why a black person cannot be the president of the United States one day.

I Am Not Your Negro brings the struggle for equal rights up to the present day by referring in passing to the young black men — Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, to name but two — who’ve been murdered by the police under tragic circumstances in recent years.

As might have been expected, Baldwin has the last word in this deceptively powerful film.

The story of the Negro in America, he says, is the story of America, and it’s not a pretty picture.

Touche.