Thanks to the popularity of the 1993 movie Schindler’s List, as well as the success of the Jewish Culture Festival in Krakow, many people assume that the Kazimierz neighborhood, where most of the city’s Jews lived prior to the Holocaust, served as the Jewish ghetto during the war.

Elsewhere in Poland, a Jewish district typically became the city’s Jewish ghetto. But this was not the case in Krakow. The Nazis considered Krakow a German city, as it had been ruled from Vienna prior to 1918, and made it their headquarters in occupied Poland.

They considered Kazimierz “too close” to the city’s center to be inhabited by Jews. Hans Frank, the Nazi governor of occupied Poland, wanted to make the city “Judenrein.” So the Nazis forced the Jews across the Vistula River to Podgorze.

Overcrowding was an obvious problem, with one apartment allocated for every four families. Windows facing “Aryan” Podgorze were bricked or boarded up to prevent contact with the outside world. Four guarded entrance gates accessed the ghetto.

While Oskar Schindler succeeded in saving some 1,200 Jews, he was not the only person in Krakow who refused to take part in the savagery of the Nazis’ “Final Solution.”

It turns out there was one “hole” through which food, information, and medicines could be brought in, and information sent out, in the otherwise hermetically-sealed ghetto.

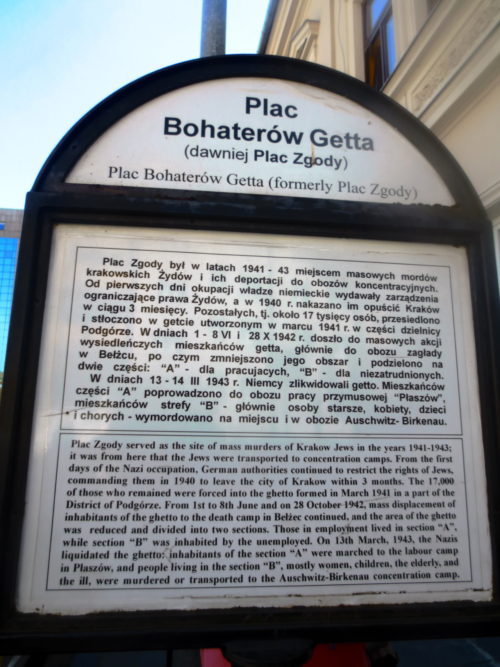

In 2005, the Plac Zgody square in Podgorze was renamed Plac Bohaterow Getta (Ghetto Heroes Square) to commemorate the memory of the inhabitants and victims of the ghetto.

The square has 64 empty chairs scattered about, representing the 64,000 Krakow Jews murdered by the Nazis.

It also houses the Apteka pod Orlem (Under the Eagle Pharmacy), which is now a museum documenting the life-saving activities of the pharmacy’s owner, Tadeusz Pankiewicz, during the war. This was the one non-Jewish business left inside the ghetto.

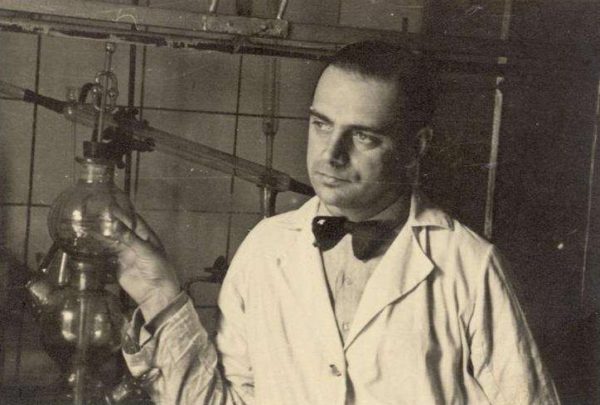

Despite a few books written about him, Pankiewicz, though having been designated by Israel in 1983 a “Righteous Among the Nations,” a term that describes non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination, remains relatively unknown.

Born in 1908 in Sambor, Poland, he went to university in Krakow and took over the pharmacy in 1933 that his father had founded in 1910. Before World War II, both Jewish and non-Jewish patients used it.

In March 1941, when the Nazis established the ghetto, the pharmacy by chance found itself enclosed there. Thanks to Pankiewicz’s endeavors, the Nazis allowed it to continue to operate.

Three other prewar pharmacies owned by non-Jews in the area relocated to the non-Jewish side of the city.

Pankiewicz and his associates, Irena Drozdzikowska, Helena Krywaniuk, and Aurelia Danek-Czort, all Catholics, provided aid and support to the ghetto’s inhabitants.

They risked their lives to undertake numerous clandestine operations, smuggling food and information, and offering shelter on the premises for Jews facing deportation to the camps.

The pharmacy helped people maintain contact with the outside world, and it enabled Polish doctors to viisit the pharmacy, providing medical attention.

Under the Eagle kept residents alive by distributing tranquilizers to help keep hidden children quiet during Gestapo raids. As well, the pharmacy provided medical care and hair dye to help disguise escapees.

It also became a hiding place for Jews and a clearing house for information about possible escape routes.

A secret vault beneath the pharmacy stored Torahs and other Jewish artifacts.

The museum re-creates the interior as it looked in the 1940s, based on photographs from the period. The space features replicas of furniture and pharmaceutical supplies.

Visitors can see the prescription room, where “recipes for survival” were dispensed to Jews trying to cope with the trying circumstances of their existence.

The duty room includes Pankiewicz’s own eyewitness accounts of day-to-day life in the ghetto, which were preserved and later published.

Films feature scenes from the ghetto deportations of May, June, and October 1942 to the Belzec death camp, and the ghetto’s final bloody liquidation in March 1943, with the remaining Jews sent either to Auschwitz or the new Plaszow concentration camp in Podgorze itself.

Following the war, the new Communist government nationalized the Under the Eagle Pharmacy, and it eventually was turned into a bar.

But in post-Communist Poland, the indifference to, and erasure from memory of, the Holocaust has been reversed, and since 2003 the pharmacy has become a branch of the Historical Museum of the City of Krakow.

After the war, Pankiewicz returned to work as a pharmacist. He died in 1993. No one should leave Krakow without paying homage to this remarkable man.

Henry Srebrnik, a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island, is currently visiting Poland.