Shamsud-Din Bahar Jabbar, the lone wolf terrorist who rammed a pickup truck into street crowds in New Orleans on January 1, killing 14 pedestrians, was radicalized by Islamic State, the jihadist organization which has left a legacy of death and destruction around the globe.

An American-born convert to Islam, he had no police record of violence, yet he was sufficiently agitated and motivated to carry out the most serious incident of terrorism in the city’s history.

Hours before he went ballistic, he posted five videos on his Facebook account proclaiming his support of Islamic State and previewing the mayhem he planned to unleash in the French Quarter neighborhood.

Since he was killed in a hail of bullets shortly after his rampage, we may never know exactly why Jabbar, 42, went off the deep end. What we do know is that he was deeply inspired by Islamic State’s online propaganda, which, in the past decade, has influenced a succession of gullible followers to engage in mass murder.

One of the most egregious examples of a self-radicalized Islamic State zealot who translated antipathy into action was Amedy Coulibaly, who in 2015 stormed a kosher supermarket in Paris, slaying four of its customers before he was fatally shot.

In 2016, an Islamic State jihadist drove a heavy truck into a crowd in the southern French city of Nice, causing the deaths of more than 80 people. And in 2017, a man driving a sport utility vehicle plowed into strollers on London’s Westminster Bridge, killing two people.

Since its formation in 2013, Islamic State has gained notoriety for mass-casualty bombings in Paris and Brussels in 2015 and 2016 and for a series of executions of foreign hostages.

Although the majority of its victims have been Christians, Shi’a Muslims have been targeted by Islamic State as well, having been condemned as apostates.

A Sunni Muslim organization, Islamic State is an offshoot of Al- Qaeda, which brought down the World Trade Center in Manhattan on September 11, 2001.

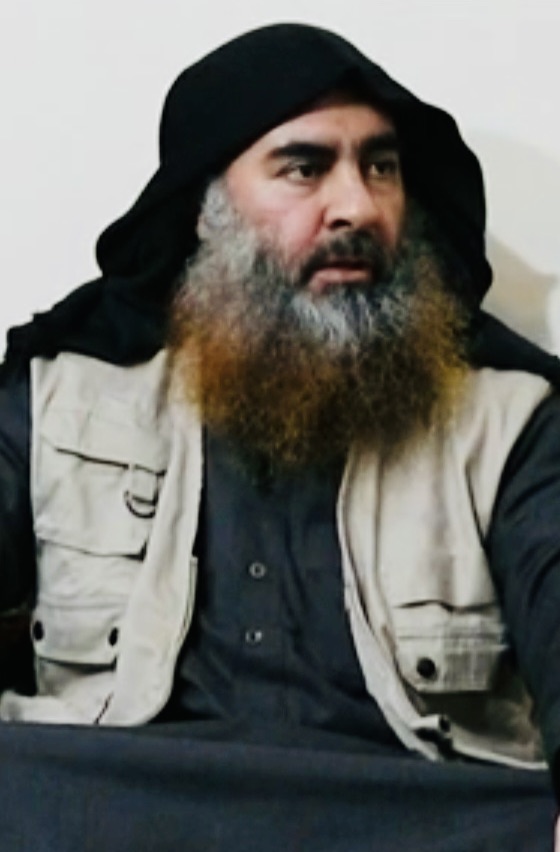

Islamic State emerged in Iraq during the U.S. occupation, which lasted from 2003 until 2011. Its founder, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, established a self-governing caliphate in parts of Iraq and neighboring Syria.

Bound by the strictest Islamic principles, centered in the Iraqi and Syrian cities of Mosul and Raqqa, and attracting an international array of acolytes, it reached its apex between 2014 and 2016.

The United States and its Western allies destroyed the caliphate in Iraq by military means in 2017, receiving valuable assistance from the Iraqi army and Kurdish militias. The caliphate in Syria was destroyed in 2019.

U.S. special forces raided Al-Baghdadi’s home in north-western Syria in October of that year. Before he could be captured alive, he detonated a suicide vest. He was 48 when he blew himself up.

His successor, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, also committed suicide when American commandos burst into his house in northwest Syria in February 2022.

Six months later, a U.S. drone strike killed Al-Qaeda’s leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, in Kabul, Afghanistan. Zawahiri assumed command of Al-Qaeda after its founder, Osama bin Laden, was assassinated by a U.S. Navy SEAL team in 2011.

These blows have greatly degraded Al-Qaeda and Islamic State, but they continue to function, particularly in Africa.

Islamic State accelerated the pace of its attacks in Iraq and Syria last summer. Its Afghan affiliate, Khorasan, bombed a memorial procession in Iran in honor of the late Qassem Soleimani, the former commander of the Quds Force — an arm of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps — and the creator of the anti-Israel Axis of Resistance.

Several months later, Khorosan terrorists attacked a concert hall near Moscow, killing scores of Russians.

The downfall of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad last month touched off concerns that Islamic State might attempt to regroup in Syria. Shortly after the sudden collapse of his Baathist regime, the Israeli Air Force bombed caches of strategic Syrian weapons so that they would not fall into the hands of Islamic State or other groups hostile to Israel.

Late last month, in a bold show of strength indicating that the United States regards Islamic State as a real and present threat, the U.S. Air Force bombed 75 of its sites in Syria. In the wake of these strikes, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that the United States will do whatever is necessary to degrade Islamic State.

The outgoing Biden administration wants to ensure that Islamic State cannot ever again exert control over wide areas of Syria. President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, warned recently that Islamic State is doing “everything it can … to regrow its capabilities” now that Assad is gone.

For the past decade, upwards of 2,000 American troops have been based in northeastern Syria to thwart attempts by Islamic State to revive itself.

Sullivan’s soon-to-be successor, Michael Waltz, has suggested that incoming president Donald Trump may not follow through on his previous vow to withdraw U.S. troops from Syria. While Trump does not want to get dragged into wars in the Middle East, Waltz added, he realizes that a U.S. military presence in Syria is essential to contain Islamic State. “We have to keep a lid on it,” he said in a reference to the jihadists.

Even if Trump leaves the U.S. garrison in Syria intact, Islamic State will doubtless press ahead with its mission to radicalize impressionable minds on the internet.

Look no further than the case of Shamsud-Din Bahar Jabbar to confirm this assumption. Even as these words are written, countless young men around the world gazing into computer screens are being seduced by Islamic State to sacrifice their lives for the cause.