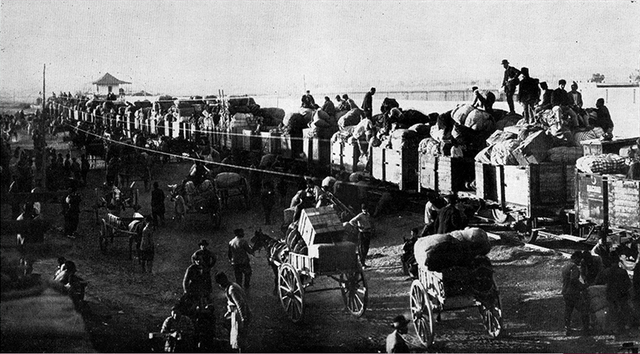

When Joe Biden became the first American president to recognize the Armenian genocide, the United States joined a select list of about 30 countries that already had recognized the Ottoman Turkish massacres of 1915.

Reacting to Biden’s move this past April, Israel’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement recognizing the “terrible suffering and tragedy of the Armenian people,” but stopped short of defining the murder of at least one million Armenians as genocide.

The Israeli government’s reticence to define this event as genocide is entirely due to its reluctance to offend Turkey, the successor state of the Ottoman Empire, which collapsed in 1918.

Israel’s timidity with respect to this sensitive issue did not stop Yair Lapid, the leader of the centrist Yesh Atid Party, from praising Biden. With the Holocaust in mind, he said he would “continue to fight for Israeli recognition of the Armenian genocide” because “it is our moral responsibility as the Jewish state.”

Now that Lapid is Israel’s alternative prime minister and foreign minister, one wonders whether he will act on his beliefs. So far, he has remained conspicuously silent, which is hardly surprising.

Succumbing to Turkish pressure, Israel has so far declined to categorize the mass slaughter of Armenians as genocide. One of Lapid’s predecessors, Shimon Peres, denounced efforts to draw a parallel between the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide. “Nothing similar to the Holocaust occurred,” he said in 2001, when Israel’s bilateral relations with Turkey were infinitely better than they have been for the past 12 years. “What the Armenians went through is a tragedy, but not genocide.”

Yet there have been Israeli voices who have called on Israel to recognize the Armenian genocide.

Twenty one years ago, the then minister of education, Yossi Sarid, announced plans to place it on the history curricula. “We Jews, as principal victims of murderous hatred, are doubly obligated to be sensitive, to identity with other victims.”

In 2011, the Knesset held its first discussion on the topic, but it was never put to a vote, even after one parliamentarian, Arye Eldad, introduced a bill to mark April 24 as Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day.

Another politician, Reuven Rivlin, who recently stepped down as Israel’s president, was an outspoken advocate of recognizing the Armenian genocide. He argued that Israel’s geopolitical needs paled in comparison with the moral necessity of recognizing the suffering of the Armenians. Be that as it may, Rivlin did not raise the issue in public during his presidency.

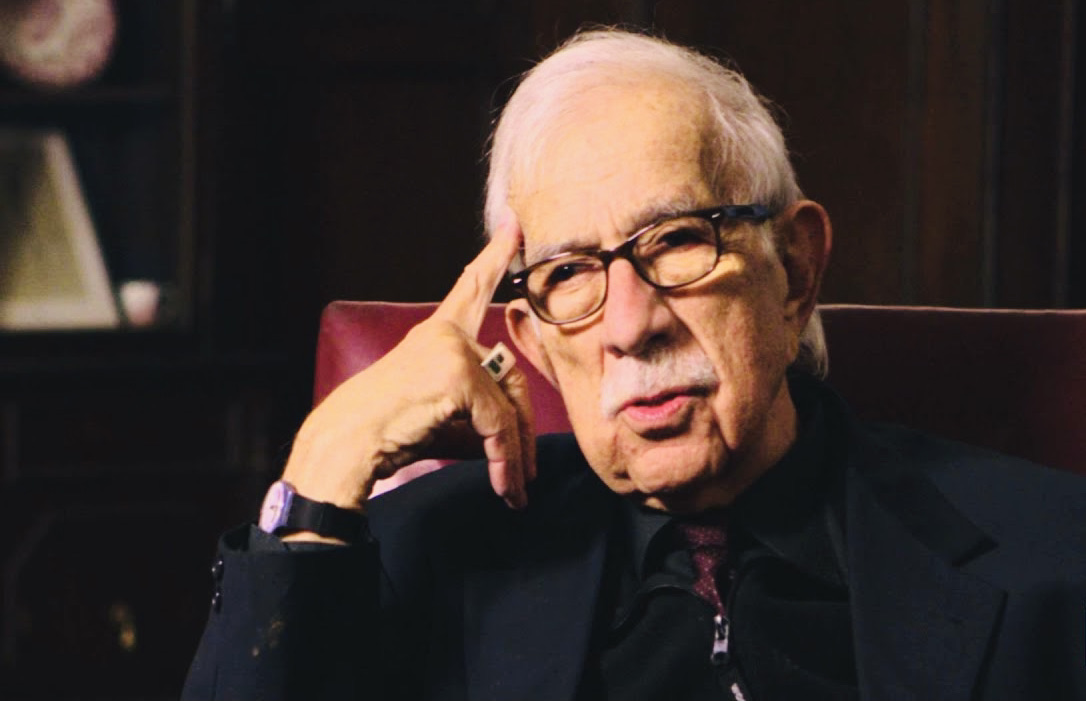

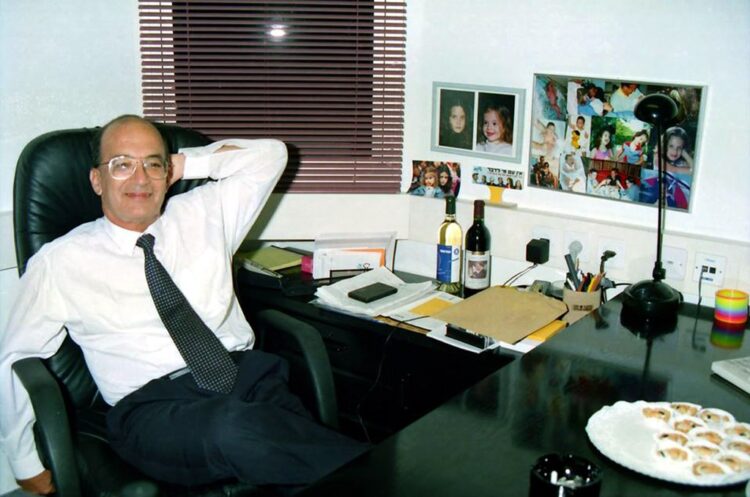

Israel Charny, an American-Israeli psychologist and the co-founder of the International Association of Genocide Scholars, understands Israel’s official position but sharply disagrees with it.

In June 1982, when he was in the midst of organizing the First International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide in Tel Aviv, he came under intense Israeli government pressure to cancel it because the Armenian genocide was on the agenda.

Charny, a former Tel Aviv University professor, discusses this unpleasant incident in an accusatory book, Israel’s Failed Response To The Armenian Genocide: Denial, State Deception, Truth Versus Politicization Of History, published by Academic Studies Press.

He had lined up a distinguished cast of personalities to attend the conference. Elie Wiesel, the novelist and a Holocaust survivor, agreed to address the opening session. Yehuda Bauer, the Hebrew University historian, and Yitzhak Arad, the director of the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial and research center, joined the organizing committee. Yoram Dinstein, the rector of Tel Aviv University, was to be chairman of the closing ceremony.

Approximately 300 academics from around the world accepted an invitation to participate.

But then politics intruded. Moshe Gilboa, an Israeli Foreign Ministry official, demanded that the conference should be cancelled, or that half a dozen of 130 lectures focusing on the Armenians should be scrapped.

A Turkish Foreign Ministry official told The New York Times that Turkey had no objection to the conference itself, but opposed “any linkage of the Holocaust to the Armenian allegations of genocide.”

The Israeli government claimed that, if the conference went ahead as planned, the Turkish government would retaliate by forcing Syrian and Iranian Jewish refugees in Turkey to return to Syria and Iran at their own risk.

Charny claims this threat was “fabricated” by Israel.

Turkey categorically denied it had issued any such threat, or that harm would come to Turkish Jews.

Nevertheless, Israel’s smear campaign against the conference worked. Wiesel resigned after Charny refused to postpone the conference or relocate it to another country. Dinstein stepped down from his position. Arad announced that the opening ceremonial session could not take place at Yad Vashem.

Charny says he was prepared to compromise by reducing the “visibility” of the Armenian question at the conference and removing the titles of the Armenian genocide in the official program.

Israel’s Foreign Ministry rejected these compromises, writes Charny. Once the ministry knew “we would not remove the Armenians or the subject in entirety,” it called for the cancellation of the conference.

“I believe the whole imbroglio could have been avoided simply by Israel telling Turkey that there was no way whatsoever to interfere with academic freedom,” he adds.

As it happened, the conference took place in Tel Aviv, at the Hilton Hotel, despite Israel’s displeasure.

Charny, of course, is deeply disappointed by Israel’s stance on the Armenians. As he puts it, “Israel’s denials are a profound moral failure that has no justification whatsoever.”

Charny’s book, while informative and brimming with indignation, is disorganized, verbose and repetitious. Nevertheless, it shines a spotlight on an inadequately reported aspect of Israel’s foreign policy.