Less than three weeks after Israel and Turkey officially restored full diplomatic relations, following an acrimonious break of four years, a Turkish naval vessel docked in Haifa in an unmistakable sign that the normalization process has begun in earnest.

The Kemalreis, a frigate, arrived in Haifa on September 3 to participate in a NATO exercise alongside the USS Forrest Sherman, a U.S. guided missile destroyer. It was the first Turkish Navy ship to visit Israel since May 2010, when Israel’s bilateral ties with Turkey sank to an all-time low following a violent incident on the high seas.

After Israeli commandos boarded the Mavi Marmara, a Turkish boat carrying humanitarian supplies to the Israeli-blockaded Gaza Strip, they killed nine pro-Palestinian Turkish activists in a firefight. Outraged by the attack, Turkey ousted Israel’s envoy in Ankara, recalled its ambassador in Tel Aviv, and drastically downgraded bilateral relations with Israel.

Six years would elapse before Israel and Turkey resumed normal relations. But further tensions lay on the horizon.

In 2018, after Israeli troops killed scores of Palestinians trying to cross the border illegally from Gaza into Israel, Turkey yet again went ballistic, ordering Israel’s ambassador to leave and recalling its envoy in Israel for “consultations.” Israel, in turn, expelled Turkey’s consul general in Jerusalem.

The seething, unresolved Palestinian issue lay at the heart of the tension. Although Turkey was the first Muslim nation to recognize Israel, Turkey regards itself as an unwavering champion and advocate of the Palestinian cause and supports a two-state solution to settle Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians.

Turkey has doubled down on this policy since Israel’s first war in 2008 with Hamas, the governing authority in Gaza.

Since then, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the head of the Islamist-oriented Justice and Development Party, has strengthened relations with Hamas and been an outspoken and incendiary critic of Israel. Deploying overheated rhetoric in his broadsides, Erdogan has repeatedly condemned Israel as a terrorist state and compared it to Nazi Germany.

In Israel’s last reconciliation process with Turkey, which lasted from 2013 to 2016, Israel took the lead in patching up ties. Israel formally apologized for the deaths of the nine Turks on the Mavi Marmara and paid $20 million in compensation to their families.

This time around, Turkey was the suitor pushing to advance normalization. This development coincided with efforts by Erdogan to improve strained relations with adversaries such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Syria.

More than a decade ago, Turkey’s policy in the Middle East could be summed up in a few choice words– zero problems with neighbors. This approach crumbled as Erdogan aggressively sought to expand Turkish influence in the region.

Having reluctantly concluded that his overbearing tactics had virtually isolated Turkey, Erdogan switched course and reverted to his old position of reducing conflicts with neighboring countries. As a result, he took the initiative in repairing relations with Israel.

Shortly after Israeli President Issac Herzog assumed office in 2021, he called to offer his congratulations. Shortly afterward, Erdogan facilitated the release of an Israeli couple in Istanbul who had been arrested and unjustly accused of espionage.

These developments took place after Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s long-serving prime minister and a fierce critic of Erdogan, was replaced by Naftali Bennett.

Erdogan was clearly pleased by Netanyahu’s exit from office, but beyond this factor, his reasons for improving relations with Israel were quite clear. Turkey and Israel share a number of vital interests, ranging from the containment of Iran, the preeminent Shi’a power in the Middle East, to mutual cooperation in the sale of Israeli natural gas to Europe.

Turkey, a Sunni Muslim nation, maintains normal relations with Iran, yet they are regional rivals. Turkey, too, is chary of Iran’s nuclear program, which Israel has lambasted. In 2020, Israel and Turkey both backed Ajerbaijan, a Muslim republic, in its war against Armenia.

Israel, having discovered huge deposits of natural gas in its territorial waters in the Mediterranean Sea, understands that the most economically viable method of shipping it to Europe is through a pipeline from Turkey. Erdogan is acutely aware that such a commercial arrangement would reduce Turkey’s heavy reliance on Russian natural gas and strengthen its standing as a transit point to European markets.

Turkey, Israel’s fifth largest trading partner, wants to upgrade its volume of trade with Israel, which reached $7 billion in 2021, and to update its 1997 free trade agreement with Israel.

Turkey believes that its bilateral relations with the United States will correspondingly improve if there is a rapprochement with Israel. Turkey’s relationship with Washington took a nose dive after it bought Russian S-400 missile batteries. In response, the United States cancelled the sale of F-35 stealth fighter jets to Turkey.

Given these inescapable factors, Erdogan invited Herzog on a state visit to Turkey this past March. It was the highest-level meeting between Israeli and Turkish leaders in some 14 years. By all accounts, the visit was a success, replete with pomp and ceremony and a cordial reception from Erdogan.

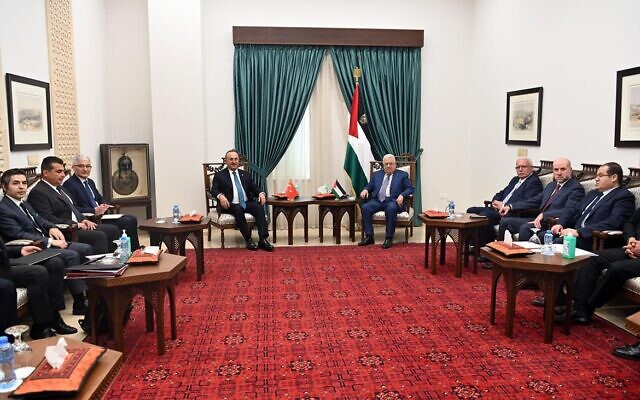

Two months later, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu visited Israel and Palestinian Authority headquarters in the West Bank town of Ramallah. His trip led to the renewal of Turkey’s aviation agreement with Israel and the restoration of Israeli-Turkish economic committees.

Speaking in Ramallah, Cavusoglu said that Turkey’s relations with Israel would not affect its stance toward the Palestinians: “Our co-ordination with the Palestinian side is a separate matter than our relationship with Israel. Our policy towards the Palestinians will not change.”

In June, Yair Lapid, the current Israeli prime minister, went to Turkey in his capacity as foreign minister. Among the officials he met was Hakan Fidan, the head of Turkish intelligence.

Around this time, Fidan’s agency and the Mossad — Israel’s external intelligence organization — cooperated in the arrest of several Iranian assassins who had been sent to Turkey to abduct or kill Israeli tourists.

On August 17, Israel and Turkey announced that full diplomatic relations would be restored and that ambassadors would be exchanged. Several days later, Cavusoglu said he would announce the name of Turkey’s new ambassador to Israel in the “coming days,” but this announcement has yet to be made.

Lapid described the resumption of relations as “an important asset for regional stability and very important economic news for the citizens of Israel.” In addition, he said, “economic. cooperation between our countries has been constantly on the rise.”

Herzog predicted it would “encourage greater economic relations, mutual tourism and friendship between the Israeli and Turkish peoples.”

On August 22, Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian Authority, visited Ankara in his second trip to Turkey in a year. In an attempt to balance Turkey’s ties with both sides, Cavusoglu assured him that Turkey’s renewed relationship with Israel would enable Turkey to “better defend the Palestinian cause.”

It has yet to be determined whether Erdogan will accede to Israel’s request to banish all Hamas operatives in Turkey. Several have been asked to leave, according to unconfirmed reports. But most of them still live and work in Turkey.

This could become a contentious issue should Israel publicly resurrect its claim that Hamas runs terrorist operations from Turkey.