Last week, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu met the leaders of Uganda and Sudan, two African countries embedded in the lore of the Zionist movement for better or worse.

Visiting Kampala, the capital of Uganda, Netanyahu said that Israel is intent on upgrading its mercurial relationship with the countries of the African continent. “Israel is coming back to Africa and Africa is coming back to Israel in a big way,” he said in a comment addressed to his host, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni.

Uganda broke diplomatic relations with Israel in 1972 when it was ruled by the erratic Idi Amin. And while Uganda has yet to renew formal ties with Israel, Museveni told Netanyahu he is “studying” the possibility of doing so.

During his whirlwind trip to Uganda, which he last visited in 2016 to mark the 40th anniversary of the Entebbe hijacking incident, Netanyahu met the de facto leader of Sudan, General Abdel Fattah al- Burhan, the head of the transitional Sovereign Council, a body established following the military coup that ousted Sudan’s longtime leader, Omar al-Bashir, last April.

Netanyahu’s meeting was reportedly arranged by the United Arab Emirates, a U.S. ally.

Pundits described Netanyahu’s encounter with Burhan as a diplomatic breakthrough because Sudan still remains technically at war with Israel. It’s unclear what tangible benefits Israel reaped from Netanyahu’s encounter with Burhan, but the fact that it took place may have been a sign that Sudan’s boycott of Israel has ended.

Sensing this, the Palestine Liberation Organization condemned the Burhan-Netanyahu meeting as “a stab in the back of the Palestinian people.”

Burhan said he had agreed to meet Netanyahu “to protect the national security of Sudan and achieve the supreme interests of the Sudanese people.” In plain language, Sudan seeks to jettison its pariah image and improve relations with the United States, which in 1993 designated it as a state sponsor of terrorism.

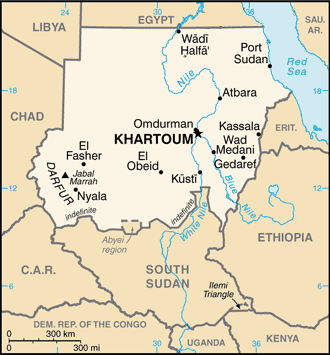

During the first half of the 1990s, Sudan permitted Osama bin-Laden, the Al Qaeda leader, to live in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, and allowed Iran to ship weapons through its territory to Palestinian forces in the Gaza Strip. In 2009 and 2012, the Israeli Air Force respectively bombed an arms convoy and an weapons factory in Sudan.

Since the coup in Khartoum last year, Sudan has realigned its foreign policy, distancing itself from Iran and moving closer to the United States. By no coincidence, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo invited Burhan to visit the United States only a day before Netanyahu and Burhan were due to meet.

Netanyahu suggested that Sudan, Africa’s biggest country, would normalize relations with Israel, but Netanyahu’s claim was disputed by Sudanese officials.

“We did not discuss normalization,” said Burhan, noting that Sudan’s overarching objective is to establish “a relationship of goodwill with the entire world.” As for Israel, he added, Sudan’s aim is to forge “a consensus between the two sides to halt all mutually hostile actions and positions.” Burhan went on to say that the Sudanese government will create a special committee to weigh the pros and cons of relations with Israel.

Sudan’s prime minister, Abdallah Hamdok, said on February 6 that Burhan had made no promise with respect to normalization. Burhan and Hamdok noted that Sudan will continue to support the right of the Palestinians to statehood. Sudan, along with the other members of the Arab League, rejected U.S. President Donald Trump’s Middle East peace plan, which was unveiled in Washington, D.C. on January 28.

In a promising sign that Israel can look forward to better relations with Sudan, Burhan said the Sudanese government will allow non-Israeli commercial airlines to use its airspace to and from Israel, thereby shortening such flights.

Until very recently, Sudan was in the forefront of the Arab struggle against Israel, having participated in several Arab-Israeli wars since 1948 and having hosted the 1967 Khartoum Arab summit, which decreed that Arab League states would not recognize Israel, negotiate with Israel or enter into peaceful relations with Israel.

The “three nos” of Khartoum more or less lasted until November 1977, when Egyptian President Anwar Sadat visited Jerusalem, delivered a speech before the Knesset and indicated he was ready to sign a peace treaty with Israel if it agreed to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and recognize the Palestinian right to statehood in the West Bank and Gaza.

Later, Sudan served as a base for Operation Moses, during which the Mossad, in conjunction with the CIA, transported some 30,000 Ethiopian Jews to Israel.

Uganda was one of the first states in Africa with which Israel established diplomatic relations. Uganda’s intricate web of ties with Israel were severed by Idi Amin in incremental steps starting with the ouster of Israeli diplomats from Uganda.

In July 1976, Israeli commandos rescued hostages in Entebbe who had been taken prisoner by Palestinian and German hijackers aboard an Air France aircraft. The commander of the Israeli strike force, Yoni Netanyahu, the brother of Benjamin, was the only Israeli soldier killed during the daring raid.

Long before these events, the Zionist movement seriously considered the region surrounding Uganda as a national home for Jews.

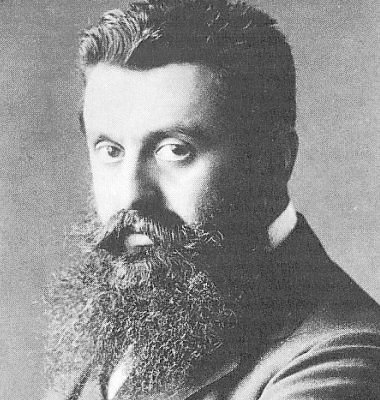

At the Sixth Zionist Congress in 1903, Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, proposed that British East Africa, which encompasses Kenya today, could be a safe haven for the Jewish people. The proposal, known as the Uganda scheme, was regarded as a stopgap measure by Herzl until Palestine, a province of the Ottoman Empire, could be proclaimed as the Jewish homeland.

The idea was originally hatched by British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain in 1902. Herzl initially rejected it, but came around for pragmatic reasons. At the Sixth Zionist Congress, the majority of delegates voted to send a commission of experts to test British East Africa’s suitability as a place of settlement. Pro-Uganda Zionists formed the Jewish Territorialist Organization, led by British writer Israel Zangwill, who advocated the establishment of Jewish colonies around the world.

The Uganda proposal was rejected by the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905. By then, Herzl had been dead for about a year. Some contend that the bitter controversy over Uganda was a contributory cause of his untimely death at the age of 44.

Although Uganda was not destined to be a Jewish homeland, Israel has invested considerable efforts to renew ties with Uganda and establish a diplomatic presence throughout the rest of Africa.

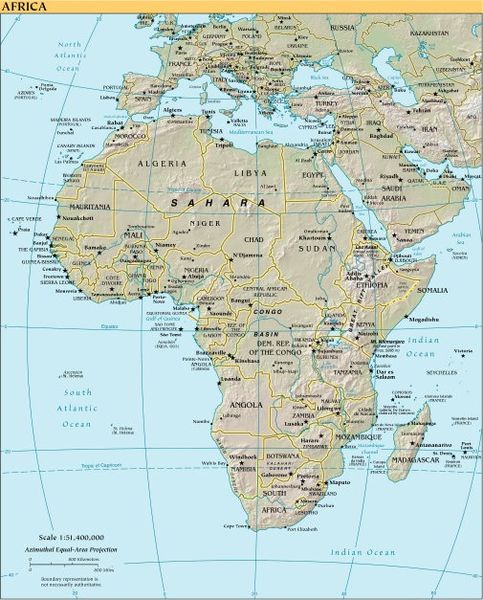

A succession of African countries broke relations with Israel in the wake of the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli wars. But in the past few years, Israel has bounced back in Africa. Israel reopened its embassy in Ghana in 2011, and in 2016, Israel renewed ties with Guinea. Last January, Israel and Chad renewed bilateral relations, and shortly afterward, Israel opened an embassy in Kigali, Rwanda.

Today, Israel maintains official ties with more than 40 of 54 African nations, but has embassies in less than a dozen countries, notably in Senegal, Angola, Ivory Coast, South Africa, Kenya, Cameron and South Sudan.

If Israel manages to add Uganda and Sudan to the growing list of African nations with which it enjoys diplomatic relations, this would be no small achievement.