Israeli and Russian interests in Syria — Russia’s closest ally in the Middle East and Israel’s longtime enemy — have been on a collision course for the past few months. Nonetheless, Israel and Russia have managed to maintain a constructive dialog to soften the edges of their differences over Syria.

Since last September, when Russia blamed Israel for the downing of a Russian reconnaissance aircraft shot down by Syria following an Israeli air raid on an Iranian weapons depot located in a Syrian Air Force base in Latakia, Israel’s relations with Russia have grown testy.

The incident, which took place on September 17, resulted in the deaths of 15 Russian airmen.

Russian President Vladimir Putin appeared to exonerate Israel when he referred to a “chain of tragic accidental circumstances” that caused the mishap. But shortly afterwards, Russia’s Defence Ministry claimed that Israel, having used the Russian plane as a cover to attack the Syrian base, was responsible. Dismissing Russia’s claim, Israel said its jets were returning to base when the Russian plane was hit by Syrian missiles.

Israel’s explanation was rejected by Russia, which proceeded to send four state-of-the-art S-300 surface-to-air batteries to Syria. Unbowed by Russia’s implicit threat, Israel said it would continue to attack Iranian military facilities in Syria.

Russia has since urged Israel to scale back its air strikes in Syria, fearing they will destabilize the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, exacerbate Israel’s conflict with Iran, and jeopardize Russia’s position in Syria.

A Russian client state since the 1960s, Syria has grown more dependent on Russia since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011. With Syria fast losing ground in that war, Russia expanded its military presence in Syria in 2015. Iran, having been aligned with the Syrians since the early 1980s, dispatched units of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps to Syria. Iran’s goals were two-fold: to add heft to Syrian and Russian efforts to defeat rebels trying to overthrow Assad, and to establish a front against Israel on the Syrian side of the Golan Heights.

Hezbollah, which fought a war with Israel in 2006 and which is dependent on Iranian weapons, came to Syria’s assistance as well.

With the Russians having launched a concerted air campaign against rebel forces, tilting the war in Syria’s favor, Russia and Israel signed a deconfliction agreement to avoid accidental clashes in the skies over Syria.

This accord broke down on September 17, after which Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu criticized Israel. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov subsequently called on Israel to upgrade coordination with Russia and claimed that renewed Israeli air attacks would not improve Israel’s security situation. Meanwhile, Putin let it be known he would not receive Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in Moscow again until things had settled down. Before September, Netanyahu conferred with Putin regularly in the Russian capital to ensure that the deconfliction pact remained intact.

In the past month-and-a-half, Israel and Russia have been in close touch to defuse lingering tensions.

On December 8, Netanyahu phoned Putin, who told him that Israel and Russia must enhance their military coordination in Syria. Four days later, an Israeli military delegation turned up in Moscow. “Understandings were reached between the delegations, and they agreed to continue working together,” an Israeli spokesman said.

On December 26, Israel bombed an Iranian base in Damascus, prompting Russia to denounce it as “provocative” and “a gross violation of the sovereignty of Syria.” Netanyahu’s reaction was swift. “We will not tolerate an Iranian entrenchment in Syria,” he said.

Putin, in a New Year greeting on December 30, expressed the hope that Russian-Israeli cooperation and partnership would develop constructively. Netanyahu, on January 4, phoned Putin to affirm his desire to “strengthen coordination through military and diplomatic channels.” Later, Netanyahu’s office added Israel was “determined to continue its efforts to prevent Iran from entrenching itself militarily in Syria.”

A week later, Israeli aircraft struck a warehouse at Damascus International Airport. “The areas hosting military positions of Iranian forces and the Lebanese Hezbollah movement have been targeted,” the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported.

On January 17, a Russian military delegation visited Tel Aviv to advance and improve “the deconfliction mechanism” with Israel. Two days later, Russia informed the Israeli government of its intention to renovate Damascus International Airport and asked Israel to halt air strikes against the facility. On January 21, in the wake of Israeli air raids against Iranian targets in Syria, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova chided Israel, saying its “practice of arbitrarily launching strikes on the territory of a sovereign state, in this case Syria, should be excluded.” Zakhorova claimed that Israel’s raids contravened international law.

On January 26, as if to counter the thrust of Zakhorava’s comments, a Russian deputy foreign minister, Sergei Ryabkov, made a conciliatory gesture toward Israel. “We in no way underestimate the importance of measures that would ensure very strong security for the State of Israel,” he told CNN. “The Israelis know this, the U.S. knows this, everyone else, including the Iranians, the Turks, the government in Damascus, know this. This is one of the top priorities of Russia.”

Tellingly, Ryabkov dismissed the notion that Russia and Iran are allies. “We do not see at any given moment completely eye-to-eye on what happens,” he said, noting that Russia had convinced Iran to withdraw its forces at least 85 kilometres from Israel’s northern border.

Ryabkov may well have also discussed a Russian proposal that Israel rejected last September. In exchange for a withdrawal of U.S. forces from eastern Syria, Russia would commit itself to expelling Iran and pro-Iranian Shi’a forces from Syria.

During Ryabkov’s visit, Israeli Immigration Minister Yoav Gallant, a former army general, claimed that Israel and Iran were on the same page regarding Iran’s presence in Syria. As he put it, “Israel and Russia have a shared interest to expel the Iranians from Syria.” According to Gallant, Syria’s success in wresting back territory from rebels has made it less reliant on Iran. Russia, too, is at odds with Iran over which country will rebuild Syria after the civil war ends, he said.

Most recently, on January 29, two high-ranking Russian diplomats visited Jerusalem for talks with Netanyahu on avoiding “friction” in Syria. The officials were Alexander Lavrentiev, Russia’s special envoy for Syrian affairs, and Sergei Vershinin, a deputy foreign minister.

“Among the issues discussed were Iran and the situation in Syria, and strengthening the security coordination mechanism between the militaries in order to prevent friction,” Netanyahu’s office disclosed. “The Russian representatives reiterated Russia’s commitment to the maintenance of Israel’s national security.”

It remains unclear what will happen next, since Syria’s bonds with Iran are very strong and Iran has no desire to withdraw its forces from Syria. But according to Amir Eshel, a former commander of the Israeli Air Force, only Russia has the power and the influence to ease Iran out of Syria. “There is no military action that is going to get Iran out of Syria,” he said in reference to Israel’s continuing air strikes. “Only a diplomatic effort can get Iran out of Syria, and this diplomatic effort has just one address — Russia.”

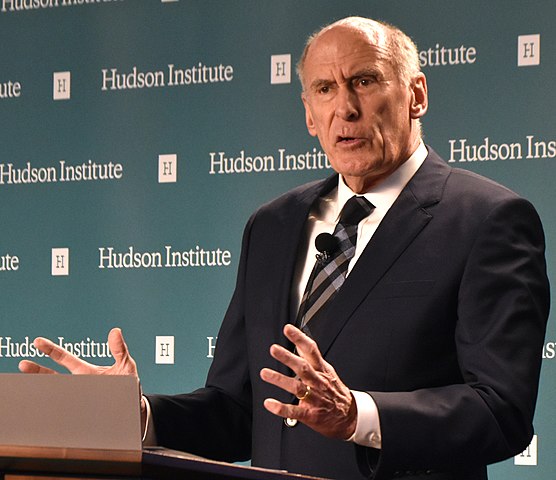

In the meantime, in a accordance with Netanyahu’s statements, Israel intends to strike Iranian targets in Syria when necessary. But as the director of U.S. intelligence, Dan Coats, noted on January 29, Israeli raids that cause Iranian casualties are likely to result in retaliatory attacks by Iran. Israel’s president, Reuven Rivlin, drew a similar conclusion a day earlier when he warned that Iran was likely to “intensify its responses” to such raids.

Although the Iranian government usually deploys proxies to attack Israel and has been careful not to engage Israel directly, Iran and Israel already have clashed several times.

Last February, Iran sent an armed drone into the Galilee, prompting Israel to attack Iran’s network of bases in Syria and Syria’s web of anti-aircraft batteries. Last May, after Israel struck the T-4 base in Syria, killing seven Iranian soldiers, Iran fired around 20 rockets toward Israeli territory. Earlier this month, after Israel bombed Iranian bases in Syria, Iran fired a missile at the Mount Hermon ski resort on the Israeli side of the Golan. The missile was intercepted by the Iron Dome anti-missile system.

It’s clear that Israel and Iran are edging toward another direct clash. This is an extremely serious matter. Further battles pitting Israel against Iran could easily spin out of control and trigger a regional war. This unpalatable scenario may well nudge Russia, which is caught in the middle between Israel and Iran, to apply the brakes on Iran’s military ambitions in Syria.