By any yardstick, Emanuel Ringelblum was a heroic figure.

As the Nazi occupation of Poland deepened, he began keeping a diary of daily events in the Warsaw ghetto, where he lived. As the oppression intensified and he came to the realization that the Germans were intent on exterminating Polish Jews, he brought together fellow Jews to document life in the crowded ghetto from a Jewish perspective. And so was born Oyneg Shabbes, a clandestine group dedicated to countering vile Nazi propaganda about the sealed ghetto.

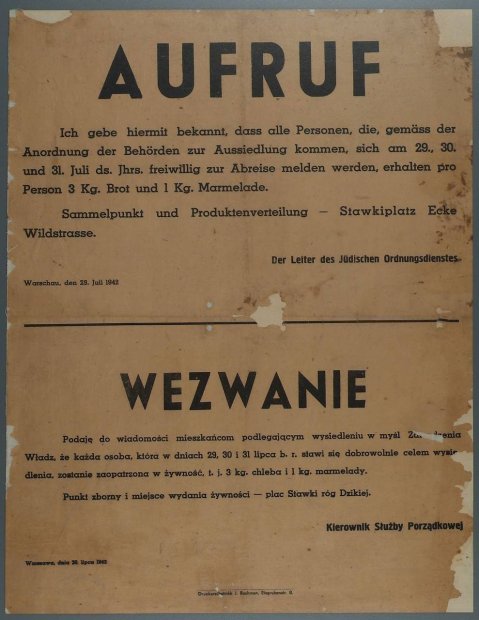

Intent on exposing Nazi lies with pen and paper, Ringelblum — a historian, Yiddishist and Labor Zionist — and his associates commissioned diaries, essays, poems and songs, collected artifacts, documents and photographs, and documented Nazi atrocities with eyewitness accounts. As Jews in the ghetto were deported to Treblinka during the great deportations of July 1942, the Jewish archivists buried 60,000 pages of documentation in metal boxes and milk cans so that Nazi crimes during the Holocaust would not go unnoticed by future generations.

The story of Oyneg Shabbes unfolds in Who Will Write Our History, a poignant documentary by Roberta Grossman based on a book by the American historian Samuel Kassow, and now playing in theatres in North America and elsewhere. This captivating film, told mainly from Ringelblum’s perspective, is composed of graphic German footage, vivid photographs, plausible dramatizations, and measured commentaries from Kassow, the historian Jan Grabowski, and the museum curator Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, among others.

Ringelblum’s assistant, the journalist Rachel Auerbach, figures prominently in the movie as well. At his request, she remained behind in the ghetto to organize and work in soup kitchens. Later, he invited her to join Oyneg Shabbes. In the reenactments, the Polish actors Jowita Budnik and Piotr Glowacki play Auerbach and Ringelblum.

Shortly after Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, a conquest that set off World War II, Ringelblum organized relief efforts in Warsaw, one-third of whose population was Jewish. The project was financed by the Joint Distribution Committee in the United States. Apart from soup kitchens, Ringleblum ran orphanages and refugee centres.

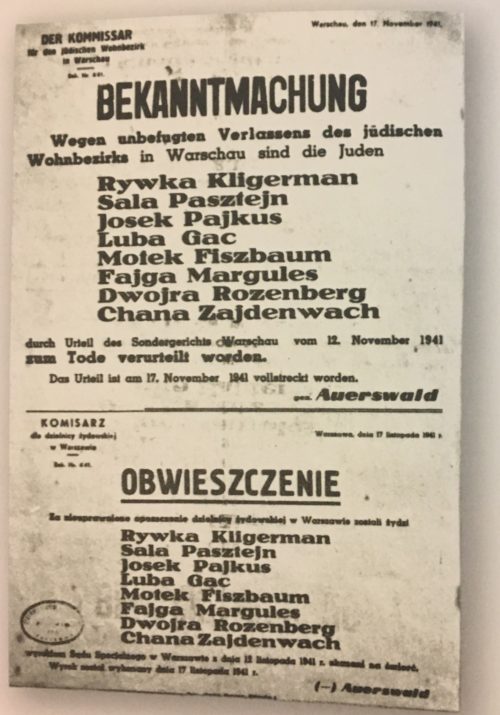

Sensing he was living in a terrible historic period, which would end with the murder of three million Polish Jews, he started a diary to document the appalling restrictions and abuses of the Nazi occupation force. He recorded the division of Warsaw into Polish, German and Jewish quarters in 1939 and the creation of the ghetto in the following year. Populated by 350,000 Jews on the eve of the German invasion, Warsaw was inundated by a further 150,000 Jews from the provinces as the tempo of Nazi atrocities increased. Jews who tried to escape were executed.

With the closure of the ghetto on November 15, 1940, Ringelblum realized that the entries in his diary, however comprehensive in scope, would have to be supplemented. He recruited new diarists, three of whom were Hersh Wasser, Abraham Lewin and Rabbi Shimon Huberband, and instructed them to gather whatever information they could obtain.

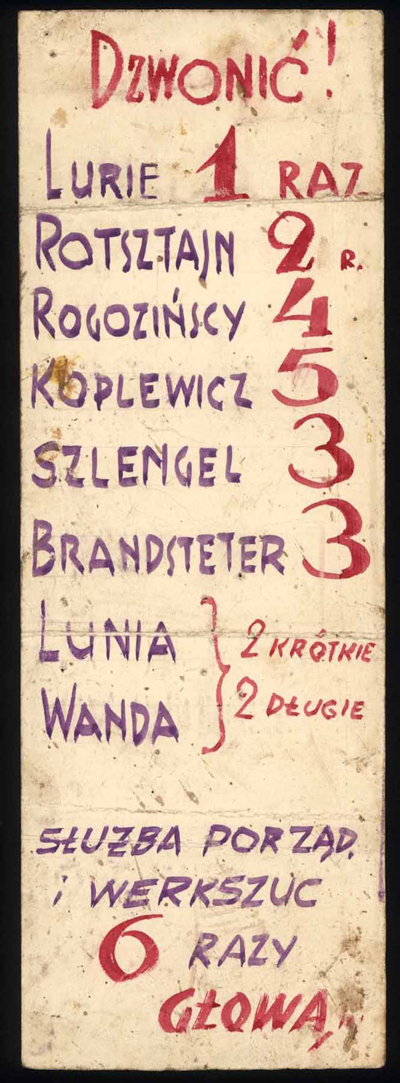

The Nazis had already circulated patently false information about the ghetto by means of films and newspaper stories, and Ringelblum was determined to set the record straight. He and his fellow diarists recorded everything — the astronomical cost of food (a fresh loaf of bread cost the equivalent of $60), the smuggling rings that supplied the ghetto with basic necessities, the 80,000 Jews who died of typhus and starvation in the first year after the establishment of the ghetto.

Ringelblum, though a cool and assiduous observer, could not always contain his emotions. “The world is turning upside down,” he wrote of the inhumane conditions. And he admitted he was hungry.

In 1942, when the Nazi machinery of genocide was cranking up to full capacity, Oyneg Shabbes learned that Polish Jews in their thousands were being gassed at Chelmno. It was the first report of Nazi mass murder. Recognizing the significance of this event in the annals of the Nazi genocide, Oyneg Shabbes printed a special bulletin and passed it on to the Polish government-in-exile in London, which, in turn, informed the BBC. The British broadcaster reported that 700,000 Polish Jews already had been murdered. No longer could the Nazis conceal their horrific crimes.

Oyneg Shabbes methodically recorded the mass deportations from the ghetto in the summer of 1942, all of which were conducted by the Jewish police force under Nazi pressure and supervision. These were days of turmoil, chaos and fear. Swept up in the dragnets were members of Oyneg Shabbes and their families. Aghast by the loss of his wife, Luba, Lewin wrote in anguish, “What a black day in my life.”

During the deportations, Oyneg Shabbes material was destroyed, but Grossman doesn’t provide details. She could have been more precise.

Having been emptied of most of its ragged inhabitants, the ghetto was left with a population of 60,000 and converted into a labor camp. Ringelblum and Auerbach, crossed into Warsaw’s Polish side. There he remained for nine months thanks to the assistance of Polish friends.

Oyneg Shabbes compiled information on the 1943 ghetto uprising, but Who Will Write Our History glosses over that courageous but doomed rebellion.

Ringelblum was hunkered down in a bunker when the Nazis obliterated the ghetto. Polish police, having detected Ringelblum’s hiding place, informed the Germans. Ringelblum, his wife and 12-year-old son were summarily shot.

Three members of Oyneg Shabbes survived the Holocaust. One of them, Wasser, knew exactly where the archives had been hidden. Almost all of them were found in 1946 and 1950, but some have been lost. Today, the surviving archives are in the possession of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Ringelblum and his fellow diarists are gone, having been killed by the Nazis, but their legacy lives on. Who Will Write Our History gives them the recognition they so richly deserve.