Israel has contravened international law by building settlements in the occupied West Bank and populating them with Jewish settlers, says prominent Israeli human rights lawyer Michael Sfard.

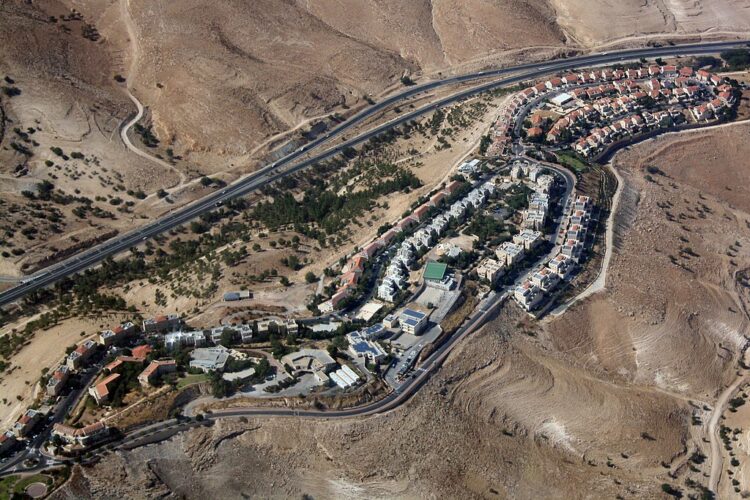

Through such methods since the 1967 Six Day War, Israel has “reengineered” the demography of the West Bank, which many Israelis regard as their ancestral homeland and which the Palestinians claim as an integral component of a future Palestinian state.

Sfard advanced this argument during a webinar on October 3 sponsored by Canadian Friends of Peace Now.

Under international law, an occupying power is forbidden to make significant changes. But in the past five decades, a succession of Israeli governments have drastically upended the landscape of the West Bank, which is currently populated by upwards of 2.5 million Palestinians and 450,000 Jews.

Israel has repaired and widened existing roads, built new highways and installed electricity lines. But above all, Israel has allowed Jewish settlers to settle in a maze of authorized settlements and unauthorized outposts in the West Bank.

According to Sfard, the Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits such activities.

By his estimate, the settlement project has flourished, with some 600,000 Israelis currently living in settlements beyond Israel’s pre-1967 border.

Under Israel’s occupation, separate but adjacent Palestinian and Jewish communities have emerged. While the civil rights of Palestinians have been circumscribed and suspended, Jewish settlers are vested with extra-territorial Israeli civil and political rights.

And in another direct violation of international law, Israeli law has been applied in East Jerusalem, which Israel annexed in 1967.

In a landmark 1991 case testing the legality of settlements in the West Bank, the Israeli Supreme Court bypassed this issue altogether by stating it could not take a position on “political” issues. The ruling, in effect, left the matter in the hands of politicians on the right and perpetuated the occupation, said Sfard, who has appeared before the high court in a number of cases challenging Israel’s occupation.

The Supreme Court, however, has handed down rulings that settlements should not be built on private Palestinian land, he added.

In his judgment, the court has grown more conservative and cautious in the last 20 years and less open to protecting Palestinian rights. “We are in a completely different era in that sense,” he said.

The court has grown more right-wing in recent years because right-wing governments have appointed conservative judges to fill vacancies.

In his opinion, the court has lost much of its credibility in terms of its ability to curb Israeli policies in the West Bank and protect the rights of Palestinians.

Asked if a system of apartheid prevails in the West Bank today, Sfard first defined the expression as a crime against humanity in which one racial group oppresses and dominates another group to perpetuate its authority.

“This is done through a denial of rights and resources,” he explained.

Sfard initially rejected this charged definition of Israel’s occupation, accepting the Israeli argument that the occupation was temporary until Israel could reach a peace agreement with the Palestinians.

Having concluded that Israel intends to keep much of the West Bank and extend its control over it through a policy of gradual annexation, Sfard today believes that Israel is committing “crimes of apartheid” against the Palestinians.

Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians cannot be resolved in a courtroom, he said. But if both sides are truly interested in negotiating a peace agreement, the law and litigation can be helpful in reaching that objective.