Last May, as Israel fought its fourth cross-border Gaza war with Hamas and Islamic Jihad, deadly ethnic violence between Jews and Arabs erupted in a string of cities, shocking and disheartening Israelis.

Israel’s president, Reuven Rivlin, compared it to a “civil war,” while an Arab member of the Knesset, Aida Touma-Sliman, likened it to the explosion of a “dormant volcano.”

It’s safe to say that the majority of Israeli Jews were surprised by the violent eruption, which claimed the lives of two Israelis, a Jew and an Arab, and caused hundreds of injuries and resulted in the widespread destruction of property.

“It came as a shock to me,” said Tzachi Hanegbi, who was then the minister of community affairs. Public Security Minister Omer Barlev was also stunned. “It very much surprised the country,” he said last September. “We weren’t prepared for it.”

The unrest, the worst in two decades, brought to the surface the long-simmering grievances of Israeli Arabs, a Muslim and Christian minority comprising 21 percent of Israel’s population.

Israeli Arabs coexist peacefully with the Jewish majority and are fairly well integrated in society. But as Barlev correctly noted, Jewish-Arab relations are bedevilled by a host of problems, which he compared to “coals sizzling under the surface” and which, he warned, “can seriously harm” Israel’s “delicate fabric.”

The rioting, lasting several days and unfolding in mixed Jewish-Arab towns such as Lod, Ramle, Acre and Jaffa, revealed what Barlev described as “a justifiable crisis in trust” between the state and its approximately two million Arab citizens.

He was implicitly referring to the discrimination Arabs generally face in employment in the private and public sectors and in government funding of municipal budgets.

The neglect of the Arab sector, Barlev said, has already led to a disproportionate intensification of crime in Arab municipalities.

Although a surprisingly high proportion of Israeli pharmacists and doctors are Arabs, Arab university graduates often come up against barriers when they apply for jobs or try to rent flats in cities like Tel Aviv and Haifa.

And as anyone who has ever visited an Arab village or town knows, they look somewhat ragged and underdeveloped, at least in comparison to their Jewish counterparts.

This is not the only problem. In recent years, more and more Arabs, particularly university graduates, have begun to identity themselves as Palestinian Israelis rather than as Israeli Arabs. This trend is exacerbated by Israel’s protracted conflict with the Palestinians and is expected to grow in the future.

Israeli Arabs are the descendants of approximately 160,000 Palestinians who chose to remain in Israel during and after the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948. During this period, about 700,000 Palestinians were displaced. Some voluntarily left their homes, while still others departed under pressure, creating a Palestinian diaspora in Arab states and outside the Middle East.

For the first 18 years of Israel’s statehood, the movements of Arabs were severely restricted by the imposition of military rule. These restrictions were abolished in 1966, but many Arabs felt like second-class citizens nonetheless.

Israeli government land expropriations aroused anger and resentment in the Arab community and prompted Arabs to mount non-violent demonstrations. Six Arabs were killed by police at Land Day rallies in the Galilee and the Negev in 1976.

Twenty four years later, in the first days of the second Palestinian uprising, 13 Arabs were gunned down by police during clashes inside Israel.

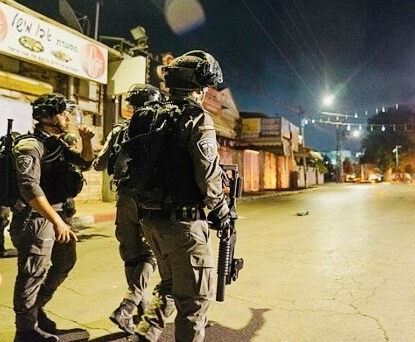

The riots this past May were set off by two separate but related events — the entry of Israeli police into the Aqsa mosque in East Jerusalem and the outbreak of the 11-day war in the Gaza Strip. Arab mobs stormed Jewish-owned shops, while Jewish vigilantes, shouting “Death to Arabs,” attacked Arabs and trashed Arab stores.

Two of the most serious incidents occurred in Lod, near Israel’s international airport, and in Acre, whose history is bound up with the Crusades.

In Lod, from which thousands of Palestinians were expelled during the 1948 war, an Arab protester named Moussa Hassouna was fatally shot by Jewish men who claimed they had acted in self-defence. A Jewish man, Yigal Yehoshua, was killed when Arabs threw a heavy rock at him.

Much of the trouble in Lod, a working-class town, occurred in Ramat Eshkol, a rundown neighborhood where seven out of 10 residents are Arabs. Overall, Arabs account for one-third of Lod’s population of 77,000.

Some Arabs in Lod claim that its mayor, Yair Revivo, a member of the right-wing Likud Party, has incited hatred against their community. Prior to the riots, he outraged local Arabs by touring Lod with Itamar Ben-Gvir, an anti-Arab member of the Knesset, and by calling “Arab crime” an “existential threat” to Israel.

Shortly after the violence in Lod subsided, Mansour Abbas — the leader of the Ra’am Party and a future supporter of Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s coalition government — met Revivo and vowed to help rebuild a synagogue torched by Arabs.

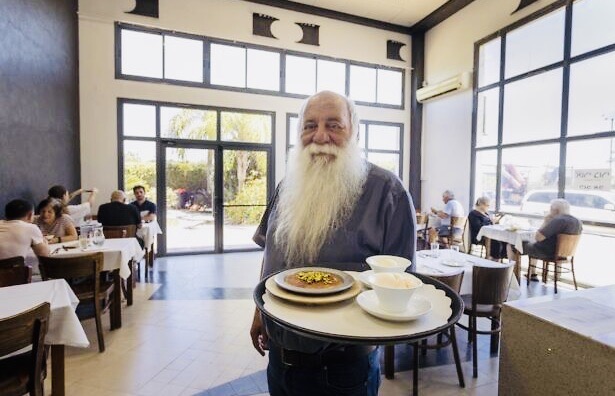

In the coastal town of Acre, where Arabs compose 30 percent of its population of 56,000, Arab rioters burned Uri Buri, a popular seafood restaurant, and the Efendi Hotel, both of which are owned by Uri Jeremias, an advocate of Jewish-Arab amity.

As a fire consumed the restored hotel, one of its guests, Aby Har-Even, a former director of the Israeli Space Agency, suffocated as smoke billowed into his room. He never regained consciousness and died in June.

Jeremias has since rebuilt his restaurant and hotel, but the wounds fester.

Since the riots, more than 1,500 people have been arrested. By one estimate, 70 percent have been Arabs. Four hundred and fifty Arabs and 35 Jews have been indicted.

Several days ago, a young Jewish man, Lahav Nagauker, was sentenced to one year in prison after having been convicted of participating in an unprovoked mob attack on an Arab motorist, Saeed Mousa, in the Tel Aviv suburb of Bat Yam last May. Badly beaten after being dragged out of his car, Mousa was rushed to hospital in critical condition. His health has since improved.

Four months ago, prosecutors filed terror charges against an Arab resident of Acre, Hassan Eid, who was charged with smashing the glass door of the Efendi Hotel, pouring oil on its floor, and setting it alight.

Last July, an imam in Lod, Yusuf Albaz, was charged with incitement in connection with a social media post in which he appeared to encourage violence against the police and Lod’s deputy mayor, Yossi Harush.

A month earlier, six Israeli Arabs and two Palestinians were charged with the murder of Yigal Yehoshua.

The riots last May have left an indelible mark, having convinced some Israelis that Arab dissatisfaction with their lot is more of a serious problem than Israel’s troubling dispute with the Palestinians.

The current Israeli government is acutely aware that it needs to be fixed. In his annual budget, tabled a few months ago, Bennett earmarked a whopping $16 billion for economic development and infrastructure projects in Arab localities. He set aside this sum after Mansour Abbas agreed to back his coalition government.

It was a step in the right direction in terms of improving the conditions of Israel’s Arab citizens and ensuring they do not have to resort to violence to achieve a measure of real equality.