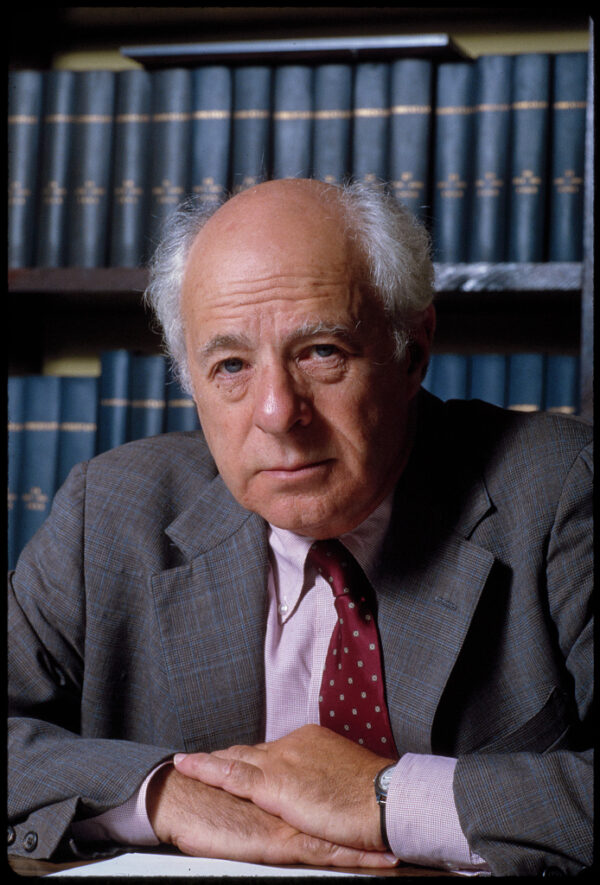

Israel’s strategic alliance with the United States took shape between the 1967 Six Day War and the 1975 Sinai II disengagement agreement. This historic process was pushed forward on the American side by politicians in the House of Representatives and the Senate, Kenneth Kolander argues persuasively in America’s Israel: The U.S. Congress and American-Israeli Relations 1967-1975, published by the University of Kentucky Press.

During this period, congressional power and influence in foreign affairs grew considerably. Until now, no study of U.S.-Israeli relations has focused primarily on the role of Congress in this transformation, says Kolander, an American historian. With this thoroughly-researched, thoughtful book, Kolander has filled a yawning gap in scholarship.

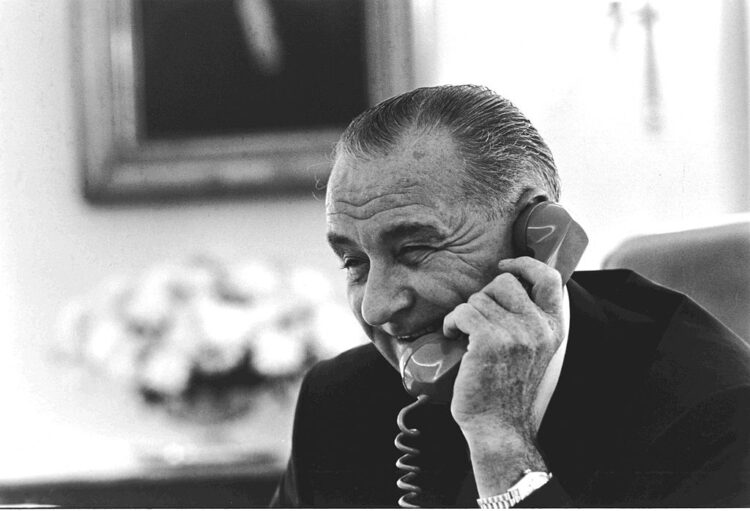

The United States and Israel developed “a much tighter relationship” with the convergence of two events. As Congress’ involvement in U.S. foreign policy reached its apex during the Cold War, the power of two presidents, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, correspondingly declined.

Factoring these developments into his calculations, Kolander says, “If the power of the presidency had remained high, the United States might not have developed such a close relationship with Israel.”

“The weakened White House had to bow to the gathered strength of a decidedly pro-Israel Congress, which helps to explain the sharp rise in U.S. military aid to Israel,” he goes on to say.

He contends that the “Israel lobby” stiffened Congress’ resolve to resist presidential initiative deemed to be disadvantageous to Israel. He identifies two influential groups that tried to reconcile U.S. and Israeli interests — the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations and the American Israel Public Affairs Committee.

The Israel lobby exploited American public opinion, Kolander acknowledges. As he puts it, “There (was) so much public support and sympathy for Israel that it (did) not face a great deal of difficulty in convincing legislators to vote its way … Many congressional members (were) happy to boldly, loudly and publicly back an ally like Israel …”

As he reminds a reader, congressional support for Israel goes back decades. Congress endorsed the Zionist movement long before the birth of Israel in 1948.

Israelis were seen as pragmatic and individualistic, characteristics prized by Americans. Israelis were regarded as gutsy underdogs, and Americans felt a “cultural closeness” to Israel. As the Cold War heated up, Americans came to perceive Israel as a vital ally in the ideological and political struggle against the Soviet Union.

By contrast, the majority of Americans did not have strong attachments to Arabs, who were viewed as the “other.”

Kolander is correct to say that the Democratic Party embraced Israel before the Republican Party. But from the 1960s onward, the interests of Israel and the Republicans began to align.

“An emerging neoconservative doctrine added another layer of support for Israel,” he notes. Jewish neoconservative intellectuals, such as the magazine editor Norman Podhoretz, advocated a more vigorous U.S. defence policy that required “a well-armed Israel.”

Joining them were Christian evangelicals. “American Christian Zionist support for Israel has proven to be substantial,” he says.

America’s commitment to Israel’s survival took a quantum leap forward after the Six Day War, when Johnson became the first president to sell offensive weapons to Israel. Yet in the first days of the war, the U.S. State Department adopted an even-handed policy. Its spokesman, Robert McCloskey, said, “Our position is neutral in thought, word and deed.”

Legislators condemned his statement, insisting that the United States had an obligation to help defend Israel. Israel’s supposedly accidental attack on an American spy vessel plying the Mediterranean Sea, the USS Liberty, did not dent congressional support for the Jewish state. In materially atoning for the deaths of 34 sailors, Israel paid millions of dollars in compensation to their families.

Less than a year after the Six Day War, Israel requested more advanced military equipment from the Johnson administration. Under congressional pressure, Johnson, in 1966, agreed to sell Israel a batch of Skyhawk jets. Four years earlier, President John Kennedy had authorized the first sale of U.S. weaponry to Israel — the defensive Hawk antiaircraft missile system.

In 1968, Israel asked the United States for 27 more Skyhawks, plus 50 Phantom fighter jets, which promised to tip the regional balance of power in Israel’s favor. The U.S. State Department and the Joint Chiefs opposed the sale. Johnson, though pro-Israel, was reluctant to accede to Israel’s request, fearing it would undercut the peace efforts of Swedish envoy Gunnar Jarring and force the U.S. into a formal alliance with Israel.

Prodded by Congress, Johnson announced that Israel could purchase the Phantom. He hoped to use the aircraft as leverage to coax Israel into reaching peace agreements with neighboring Arab nations and the Palestinians. As Kolander says, Johnson’s land-for-peace formula signalled a major change in U.S. Mideast policy.

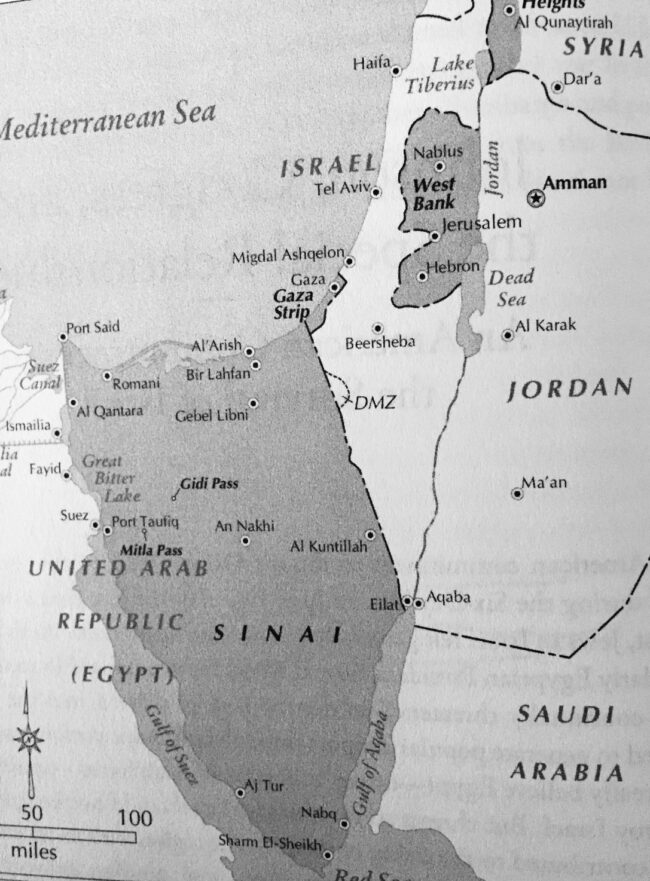

His predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower, had issued an ultimatum to Israel in 1957 to vacate the captured Sinai Peninsula, and Israel complied. But for years after the Six Day War, Israel remained entrenched in the Sinai and the Gaza Strip, while steadfastly refusing to withdraw from the West Bank and the Golan Heights.

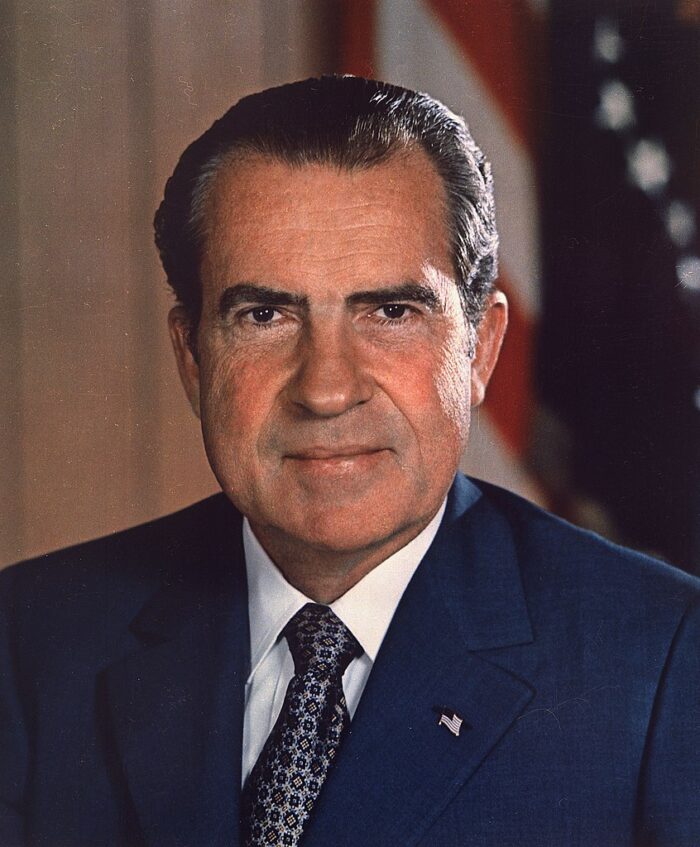

By Kolander’s reckoning, President Richard Nixon regarded Israel as an important friend and sought a closer alliance with it. Yet he pursued a balanced position on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

During Nixon’s first term in office, Congress secured larger military aid packages to Israel. But two key senators staked out very different positions.

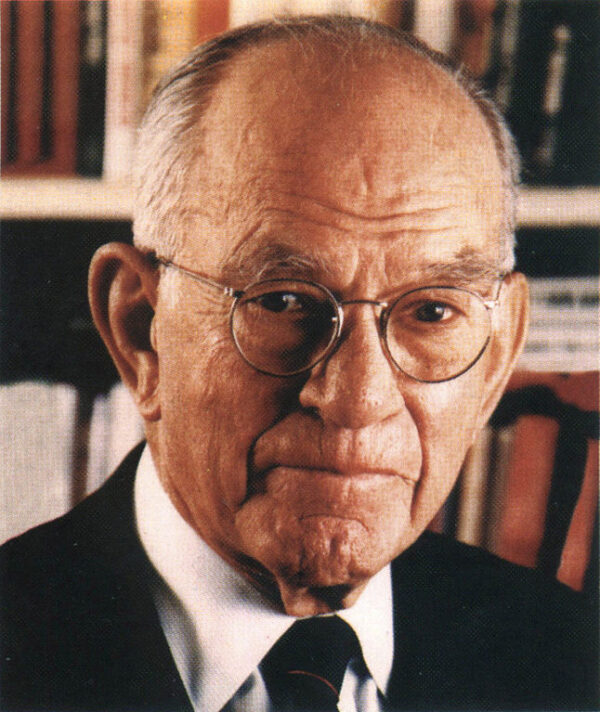

William Fulbright, a Democratic senator from Arkansas, was chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from 1959 to 1975. While he considered himself favorable disposed toward Israel, he viewed U.S. support for Israel as a liability because it soured relations with Arab states and could undermine efforts to achieve detente with the Soviet Union. He called for an even-handed approach and regarded increased arms sales to Israel as a threat to a potential peace agreement in the region.

Henry “Scoop” Jackson, the Democratic senator from Washington, viewed the Arab-Israeli dispute through the lens of the Cold War and believed Israel could protect American interests in the Middle East. Consequently, he advocated more sales of U.S. military equipment to Israel.

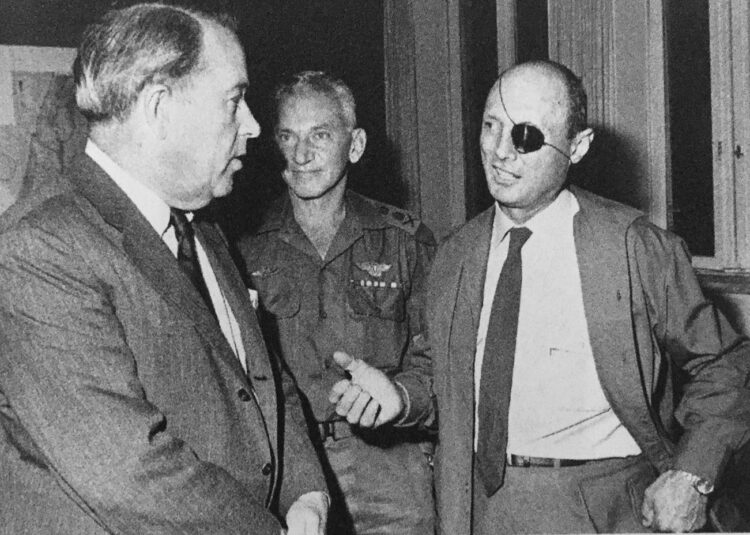

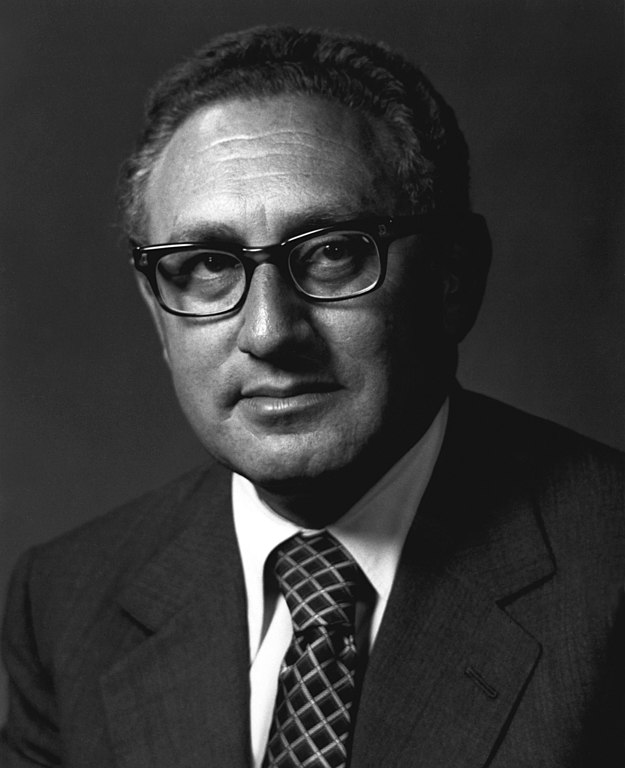

The question of arms sales arose with a vengeance during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. When Israel ran short of weapons, the Nixon administration intentionally delayed a resupply. U.S. officials believed that Israel would defeat Egypt and Syria without extra supplies, while Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger thought that only a stalemate on the battlefield would lead to peace talks between Israel and its Arab adversaries.

Many members of Congress, however, urged Nixon to replenish Israel’s stock of weaponry. On October 14, eight days after the outbreak of hostilities, Nixon ordered an unprecedented airlift of supplies. (Several days later, I heard roars in the sky. Looking upwards, I caught sight of giant Galaxy aircraft flying over Tel Aviv to Israeli military bases).

In the wake of the war, U.S. legislators argued that further military assistance would encourage Israel to take manageable risks in postwar peace negotiations with the Arabs. Nixon and Kissinger adopted a diametrically different outlook. Nixon angrily threatened to cut off “every bit of aid” to Israel if it was not forthcoming in its disengagement talks with Syria. But with Congress nipping at his heels, Nixon funnelled $3.3 billion in assistance to Israel after hostilities had ended.

Gerald Ford succeeded Nixon following his resignation in 1974 over the Watergate scandal. Ford took a harder line toward Israel. With the United States blaming Israel for the collapse of peace negotiations with Egypt in 1975, Ford, in a “reassessment,” suspended new arms deals with Israel and slowed the delivery of new weapons already in the pipeline. Ford and Kissinger sought to disabuse Israel of the notion that it could have both territory (the Sinai) and peace.

Shortly afterward, 76 out of 100 U.S. senators signed a letter urging Ford to be responsive to Israel’s request for $2.5 billion in military and economic assistance. In short order, Ford abandoned his “reassessment” policy, while Israel signed the Sinai II accord under which it was required to relinquish the Abu Rodeis and Ras Sudr oil fields to Egypt. Under that accord, the United States agreed to send troops to an early warning station in the Sinai and vowed not to advance future peace proposals without Israel’s approval.

The debate in Congress over Sinai II was at times acrimonious. James Abourezk, a senator of Arab descent, wanted to restrict weapons sales to all countries embroiled in the Arab-Israeli dispute, while senators like Joe Biden voiced technical concerns. “Biden did not necessarily disagree with the substance of the agreement but, rather, the manner in which the (Ford) administration subverted the Senate’s constitutional authority on treaty-making,” says Kolander.

In the wake of Sinai II, he states, the White House lost its leverage over pressing Israel to accede to a broader Arab-Israeli peace plan. “Billion-dollar weapons sales had become a matter of fact, regardless of Israel’s willingness to compromise in peace discussions and return the occupied areas, especially the West Bank.” During this era, he says, Congress forced increasing weak presidents, such as Jimmy Carter, to “move closer to Israel.”

Congress, not the executive branch, pushed for a “decidedly pro-Israel” foreign policy. As he says, “Consecutive administrations tried to pressure Israel to leave the occupied territories, primarily by threatening to restrict weapons sales. But Congress would not have it. Congress ensured that Israel would receive unprecedented levels of American-made weaponry and thereby empowered Israel to dominate regional diplomacy.”

Kolander admits that Congress’ pro-Israel stance was in keeping with American public opinion.

“Legislators are happy to advance a pro-Israel position, regardless of the impact on the Middle East or other U.S. interests, because they are generally concerned with representing their constituents and getting reelected.”

Further, Congress has used Israel to play a larger role in U.S. foreign policy decision-making and in funding domestic projects.

Kolander writes that U.S. military assistance to Israel has “moved well beyond a moral commitment” to its survival and now provides “the ammunition for an indefinite occupation of certain Arab lands” like the West Bank.

In summing up, he says, “Israel (has) managed to have its cake and eat it, too — billion-dollar military assistance from the United States without pressure to leave the territories.”

And that’s where matters essentially stand today.