Israel and the United States are the best of friends and allies. Indeed, Israel is probably the United States’ closest, most reliable ally in the Middle East. Periodically, however, differences arise and sparks fly, creating something of a crisis atmosphere. And then the tempest subsides, as if nothing had happened.

This is precisely what occurred in the waning days of March after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu fired Defence Minister Yoav Gallant — who still remains in his position — and U.S. President Joe Biden voiced concern about the Israeli government’s draconian plan to overhaul the judiciary.

Netanyahu’s proposal, which would weaken the power of the Supreme Court and alter the time-honored system of checks and balances to his advantage, has brought hundreds of thousands of protesters to the streets in numerous mass demonstrations in several Israeli cities.

The protests have drawn the United States into the volatile issue.

During his visit to Israel this past January, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken referred to Netanyahu’s proposed legislation when he said that shared democratic values are at the heart of Israel’s relationship with the United States. Blinken’s comment was widely seen as an implicit criticism of Netanyahu’s scheme to change the balance of power between the high court, the executive and the legislature. (Democratic values obviously are not at play when it comes to Washington’s relations with autocracies like Saudi Arabia or illiberal European nations like Poland).

By the same token, Tom Nides, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, has urged Netanyahu to slow down the process of implementing judicial reforms and to do so in a spirit of national unity and compromise.

With massive protests continuing to flare in Israel, Gallant called for a pause, saying the controversial legislation posed a threat to Israel’s security. Gallant’s recommendation prompted Netanyahu to abruptly sack him, alarming the Biden administration. It was against this heated backdrop that Biden dropped a bombshell.

As he boarded his personal plane, Air Force One, at the Raleigh-Durham airport in North Carolina on March 28, he said, “Like many strong supporters of Israel, I’m very concerned. And I’m concerned that they get this straight. They cannot continue down this road. And I’ve sort of made that clear. Hopefully, the prime minister will act in a way that he can try to work out some genuine compromise, but that remains to be seen.”

When a reporter asked Biden whether he would invite Netanyahu to the White House, an invitation he is eager to receive, Biden said, “No,” emphatically snubbing Netanyahu. For good measure, Biden added, “Not in the near term.”

Biden insisted, unconvincingly, that he was not interfering in domestic Israeli politics.

Shortly afterward, the spokesman of the U.S. National Security Council, John Kirby, blasted the legislation being advanced by Netanyahu’s far right-wing coalition government, saying it “flies in the face of the whole idea of checks and balances.”

Responding to the U.S. barrage, Netanyahu initially tried to downplay the rift. “I have known President Biden for over 40 years, and I appreciate his longstanding commitment to Israel. The alliance between Israel and the United States is unbreakable and always overcomes the occasional disagreements between us.”

In a defence of the legislation, he said, “My administration is committed to strengthening democracy by restoring the proper balance between the three branches of government, which we are striving to achieve a broad consensus.”

And then he angrily declared, “Israel is a sovereign country which makes its decisions by the will of the people and not based on pressures from abroad, including from the best of friends.”

With Netanyahu having agreed to suspend consideration of the legislation for at least one month, the Biden administration on March 29 retreated from its hardline position of the day before.

In a reference to Netanyahu’s speech suspending the legislation, Kirby said, “He talked about searching for a compromise. He talked about working toward building consensus with respect to these potential judicial reforms.”

Kirby, in another nod toward Netanyahu, said, “You don’t always agree with everything your friend does or says. The great thing about a deep friendship is that you can do it.”

And in an unmistakable acknowledgement that the United States does not question Israel’s sovereignty, Kirby said that Israel is “a sovereign state, and sovereign states make sovereign decisions.”

Speaking virtually at a White House summit on democracy on March 29, Netanyahu reaffirmed Israel’s strategic ties with the United States. As he put it, “I want to assure you that the alliance between the world’s greatest democracy and the strong, proud and independent democracy — Israel — in the heart of the Middle East is unshakeable. Nothing can change that.” Netanyahu went on to say that Israel will always remain a beacon of democracy in the region.

With that exchange, Israel’s latest tiff with the United States appeared to end on a cordial note. But this hardly means that new problems will not arise.

Last week, the United States expressed dissatisfaction with Israel’s decision to allow Jewish settlers to return to four settlements in the West Bank that were abandoned as part of its unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip in 2005. A U.S. State Department spokesman called it “particularly provocative and counter-productive.” Israel’s ambassador to the U.S., Mike Herzog, was summoned to the State Department for what was described as “a private dressing-down.”

And, of course, Netanyahu is at odds with Biden over the concept of a two-state solution to resolve Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians. Under U.S. pressure, Netanyahu paid lip service to it for several years after his reelection in 2009, but eventually he dumped it. Today, he offers the Palestinians in the West Bank nothing more than a measure of autonomy, the right to manage their own affairs and collect their garbage.

If Netanyahu waters down his judicial legislation, he may well try to appease the extremists in his government by expanding the array of settlements in the West Bank. This would certainly engender more strife between Israel and the United States.

Iran could also be a troublesome issue. Netanyahu vehemently opposes the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, from which the United States withdrew unilaterally in 2018. But until recently, the Biden administration attempted to revive it in what turned out to be futile talks in Vienna.

Netanyahu’s outspoken son, Yair, claims the State Department has financed the anti-overhaul protests to topple his father so that the United States can rejoin the Iran deal. Nides denounced the accusation as “absurd,” while the State Department dismissed it as “demonstrably false.”

Biden has known Netanyahu since his days as a U.S. senator, and while they have had disagreements over the Palestinians and Iran, they have managed to preserve their friendship. They last met in Jerusalem in the summer of 2022.

Israel’s dispute with the United States over judicial reform echoes previous conflicts.

The United States was the first country to recognize Israel’s declaration of statehood in 1948, but Washington was not hesitant to endorse policies that upset Israel.

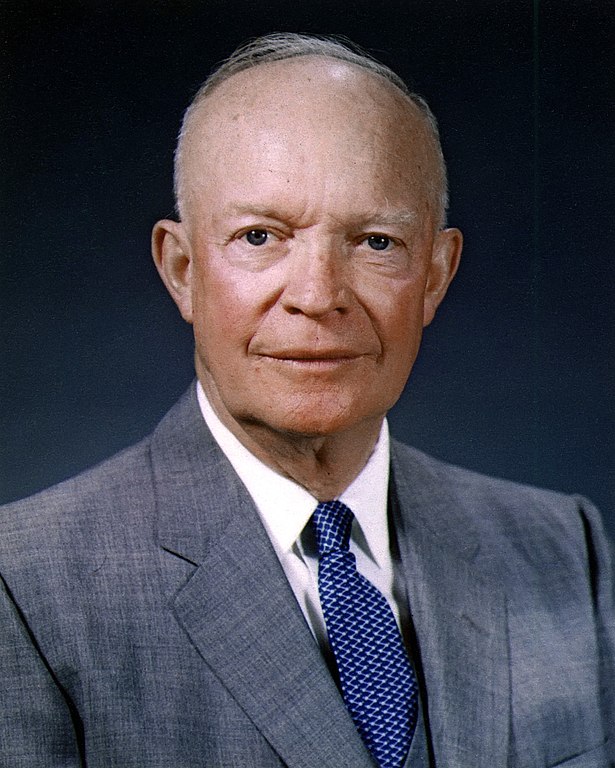

Much to Israel’s chagrin, Harry Truman called for the return of Palestinian refugees to their former homes in Israel. Dwight Eisenhower temporarily halted economic aid to Israel after it carried out retaliatory raids in the West Bank. Eisenhower, too, forced Israel to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza following the 1956 Sinai war. John F. Kennedy, the first president to break the U.S. arms embargo against Israel, annoyed Israel with his insistence to inspect its budding nuclear program and reopen the Palestinian refugee file.

Lyndon Johnson, his successor, upgraded strategic relations with Israel after the Six Day War, during which the State Department declared the United States to be neutral. Richard Nixon replenished Israel’s dwindling arsenal during the Yom Kippur War, but pressed Israel to pull out of the occupied territories. Gerald Ford announced a “reassessment” of bilateral relations with Israel after it refused to withdraw from a portion of the Sinai.

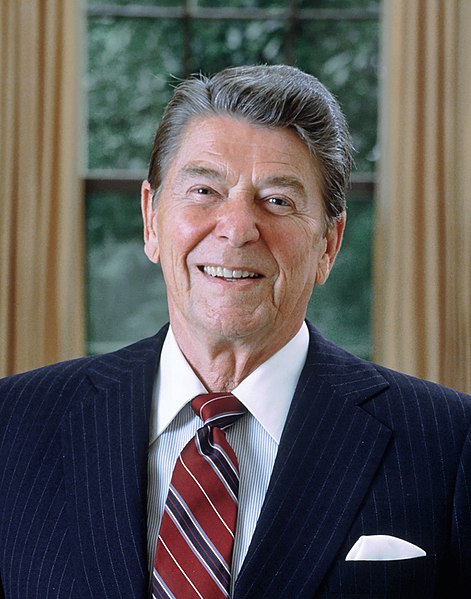

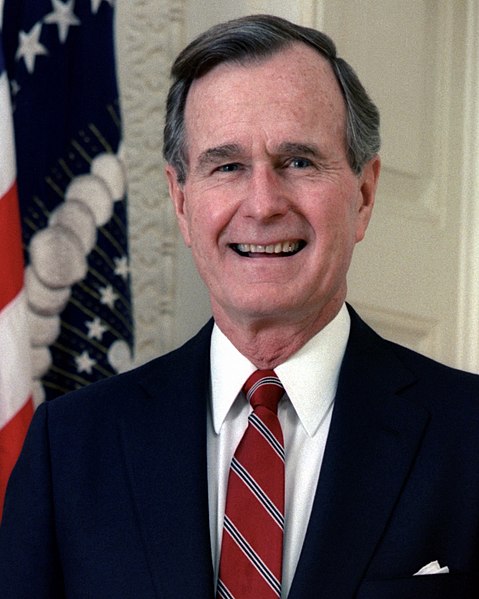

Ronald Reagan, though generally friendly to Israel, withheld aircraft after it annexed the Golan Heights and the Israeli Air Force bombed Beirut during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon. Reagan’s vice-president, George H.W. Bush, criticized Israel for having destroyed Iraq’s nuclear reactor.

Jimmy Carter incurred Israel’s wrath by showing sympathy for the Palestinian cause and exerting pressure on Israel to cede the West Bank to the Palestinians. Bush cancelled loan guarantees to Israel due to settlement construction in the West Bank. Bush’s secretary of state, James Baker, was caustically critical of this facet of Israeli policy.

Bill Clinton was extremely supportive of Yitzhak Rabin’s rapprochement with the PLO and his peace agreement with Jordan, but clashed with Netanyahu after he became prime minister. Barack Obama provided Israel with an unprecedented military aid package, but he incurred Netanyahu’s ire by lambasting the settlement project in the West Bank, calling for an Israeli withdrawal to the pre-1967 armistice lines, and promoting the Iran nuclear accord.

Donald Trump showered Israel with gifts ranging from his transfer of the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem to his recognition of the Golan as Israeli sovereign territory. In addition, Trump played a pivotal role in brokering the Abraham accords. Yet he and Netanyahu sparred over Netanyahu’s desire to annex the Jordan Valley without an acceptable Israeli quid pro quo, prompting Trump to accuse Netanyahu of lacking a sincere desire to make peace with the Palestinians.

So, yes, Israeli prime ministers and American presidents have historically clashed over various issues, but these altercations have not really affected the core values and interests that bind Israel with the United States.

Nor will the constitutional crisis currently convulsing Israel.