Forty years ago, on March 26, Israel and Egypt signed a peace treaty, the first between the Jewish state and an Arab nation.

It has endured despite an array of challenges — the assassination of an Egyptian president, Israel’s invasion of a neighboring country, the eruption of the first and second Palestinian uprisings, and a deep strain of anti-Israel animus in Egypt.

Israel’s historic rapprochement with Egypt — the most powerful and influential Arab state — was preceded by three events that facilitated it.

The Yom Kippur War, which broke out in 1973, convinced Egyptian President Anwar Sadat that Egypt would be better off coming to terms with Israel rather than continuing to confront it militarily. Egypt, having fought previous wars with Israel in 1948, 1956, 1967 and 1969-1970, concluded it could no longer squander scarce resources for the Palestinian cause. Egypt, too, sought to distance itself from its alliance with the Soviet Union and reestablish relations with the United States, Israel’s chief ally.

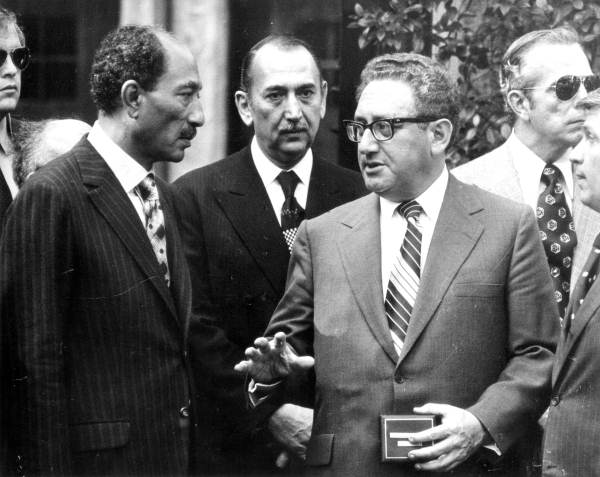

Henry Kissinger, the U.S. secretary of state, laid the foundation for the peace treaty by hammering out a series of disengagement agreements that required Israel to pull out of the Sinai in incremental stages. Syria, which launched the 1973 war in concert with Egypt, was an active participant in Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy.

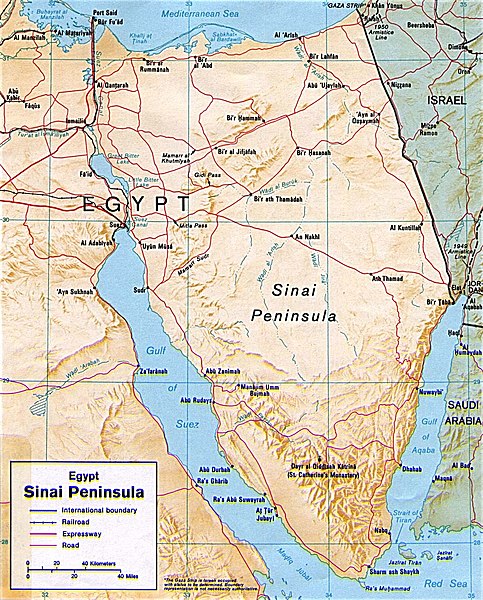

Sadat, having learned that the Israelis were ready to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula in its entirely in exchange for peace and normalization, flew to Israel in 1977 and, in a dramatic and unprecedented gesture, offered to end Egypt’s state of belligerence with Israel. Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin was delighted by Sadat’s visit and assumed that an Israeli pullout from Sinai would obviate the necessity of Israel giving up the West Bank or the Gaza Strip, an expectation harbored by the Egyptians.

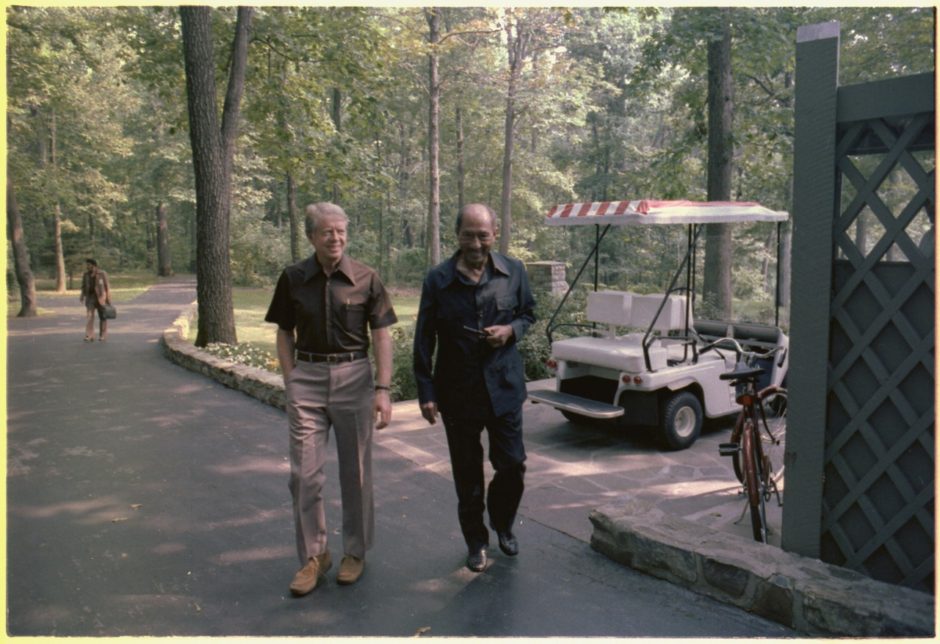

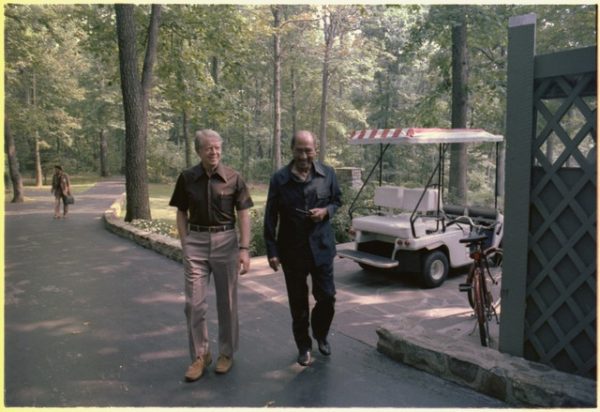

In the following year, Israel and Egypt signed the Camp David agreement after 12 days of arduous negotiations overseed by the president of the United States, Jimmy Carter. The accord envisioned autonomy for the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza — which Israel had occupied in the 1967 Six Day War — and peaceful relations between Israel and Egypt.

Sixteen months after Sadat’s trip to Israel, Begin and Sadat went to Washington, D.C. to sign the peace treaty. Wide-ranging in scope, it called for mutual recognition and normalization, the gradual pullout of Israeli forces and civilians from Sinai, the demilitarization of the Sinai, the free passage of Israeli ships through the Suez Canal, and the recognition of the Strait of Tiran and the Gulf of Aqaba — flashpoints in the 1967 and 1973 wars — as international waterways.

Within about a year, Israel and Egypt exchanged ambassadors. As well, regular flights between Tel Aviv and Cairo were started and Egypt began selling oil to Israel from its refineries in the Sinai.

Since 1982, the peace treaty has been monitored by the Multinational Force and Observers, an international peacekeeping force established by the United States.

For Israel, the peace treaty was a great strategic achievement inasmuch as it neutralized Egypt as a potential enemy. Egypt regained the Sinai and restored its relationship with the United States. Like Israel, Egypt would be the recipient of generous U.S. military and economic aid.

The peace treaty was generally welcomed in Egypt, but denounced by the Arab world. Critics assailed Sadat as sellout who had turned a blind eye to the construction and expansion of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza and the glacial pace of Palestinian autonomy talks.

Sadat was assassinated by Islamic radicals in 1981. His successor, Hosni Mubarak, had been vice-president and the commander of the air force.

While Mubarak abided by the military terms of the peace treaty, he gutted much of it by discouraging Egyptian tourism to Israel and restricting cultural exchanges with Israel. Mubarak’s strategy was to preserve the peace treaty while appeasing Egyptians opposed to it. Which is why Israelis usually describe it as a “cold peace.”

Over the years, Mubarak was subjected to intense pressure by nationalists and Islamists to abrogate the peace treaty. They claimed that Israel was an aggressive power that subjugated the Palestinians. Unwilling to follow their advice, Mubarak registered his unease with Israel by recalling a succession of Egyptian ambassadors in Tel Aviv. Egyptian envoys were recalled in 1982, following Israel’s thrust into Lebanon to destroy Palestinian bases, and yet again in 1987 and 2000 after the eruption of Palestinian rebellions in the West Bank and Gaza. Egypt also recalled its ambassador in Israel after the outbreak of the second Gaza war in 2012.

Israel’s bilateral relations with Egypt were sorely tested after Mubarak’s ouster in 2011 during the first phase of the Arab Spring revolt. In 2011, Egyptian a mob ransacked the Israeli embassy in Cairo, forcing Israel’s envoy and his staff to flee to Israel.

The election in 2012 of Mohammed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, was another fraught moment in Israel’s ties with Egypt. Morsi, a member of the vehemently anti-Israel Muslim Brotherhood who had once compared Jews to apes, grudgingly honored the peace treaty but made it clear his sympathies lay with the Palestinians.

In 2013, Morsi was overthrown by the defence minister he had appointed, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, and was subsequently imprisoned. Sisi, an ardent foe of the Muslim Brotherhood, has upgraded Egypt’s security cooperation with Israel. He has joined Israel in imposing a blockade on Gaza, which is ruled by Hamas, an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood. He has destroyed scores of Hamas smuggling tunnels running from Sinai to Gaza. He has brokered ceasefires between Israel and Hamas. He has enlisted Israel’s assistance in fighting an insurgency launched by Sinai Province, an Islamic State affiliate.

Israel has allowed Egypt to deploy more troops and military equipment in Sinai than is technically permitted by the peace treaty. And Egypt has allowed the Israeli Air Force to bomb Sinai Province bases.

Despite the fact that Israel and Egypt consider Hamas and Sinai Province common enemies, the Egyptians have not shown the slightest inclination to improve relations with Israel in such fields as tourism and culture. Egyptian artists, academics and journalists oppose normalization and boycott Israel, while newspapers in Egypt commonly demonize Israel and dehumanize Jews. Egypt, though, has agreed to buy billions of dollars worth of Israeli gas from fields in the Mediterranean Sea.

Reciprocal visits between Israeli and Egyptian cabinet ministers since Mubarak’s downfall have been virtually nonexistent, though Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has met Sisi at the United Nations. Sisi has said he will not pay a visit to Israel until the Palestinians achieve statehood. Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry has visited Israel once.

For all intents and purposes, the peace treaty has been a success. Although it has not yielded complete normalization of relations between Israel and Egypt, it has relieved them both of a huge military burden, stabilized the region to some extent, and proven that enemies are capable of reconciliation.