The battle of Iwo Jima, one of the fiercest of World War II, raged from February 19 to March 26, 1945, claiming the lives of 28,000 Japanese and American soldiers and leaving a legacy of post-traumatic stress among some of the survivors. But since 1995, Iwo Jima has been the world’s only battlefield where former enemies gather in an annual ceremony to promote peace and reconciliation.

The Pacific island’s dual image is reflected in a fine documentary, Iwo Jima: From Combat to Comrades, which will be broadcast by the PBS network on Tuesday, November 10 from 8 p.m. to 9 p.m. (check local listings) to mark the battle’s 70th anniversary.

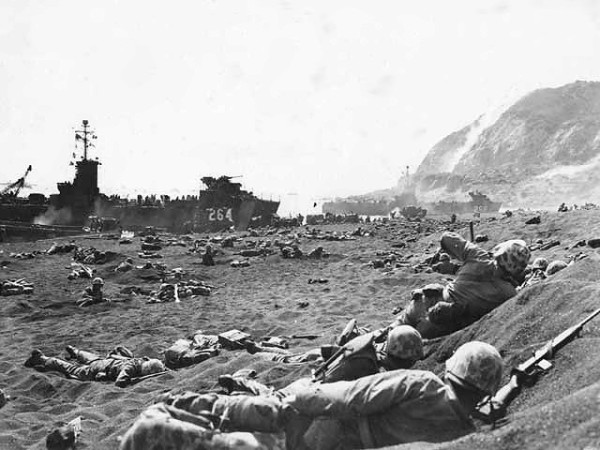

A melange of vivid newsreel footage and stark reminiscences of ex-combatants, the film takes viewers to a palm-fringed dot in a vast ocean where 22,000 entrenched troops of the Japanese Imperial Army faced an amphibious landing of nearly 70,000 U.S. marines.

The Americans coveted the eight-square-mile Japanese island because its two airfields were regarded as strategically important in the looming showdown with Japan. They would be used to launch air attacks on the Japanese home islands before armadas of U.S. troops invaded and occupied them.

Realizing that Iwo Jima was strongly fortified, the U.S. Air Force pounded it for 72 days before the first wave of marines hit its sandy beaches. A Japanese survivor, now 89, recalls the bombardment as “death and chaos.” The bombings, however, had little effect because Japanese soldiers were holed up in a formidable web of tunnels, bunkers and pillboxes.

Ironically enough, the Japanese commander was a Harvard University graduate. The men under his command were well trained and prepared to shed blood for the emperor — a living diety — and the homeland. To them, the notion of surrender was anathema. But being vastly outnumbered, they knew they had lost the battle even before it had begun.

The first marines to land on the black volcanic sands encountered little fire. But as more soldiers poured in, the Japanese responded with full force.

Judging by the interviews, the Americans just wanted to survive and go back home to their loved ones. Many, though, returned in body bags. Twenty seven Americans, having displayed uncommon bravery and valor, won the nation’s highest military award, the Medal of Honor. Hershel “Woody” Williams, who appears in the film, was one of the winners. President Harry Truman personally placed the medal around his neck.

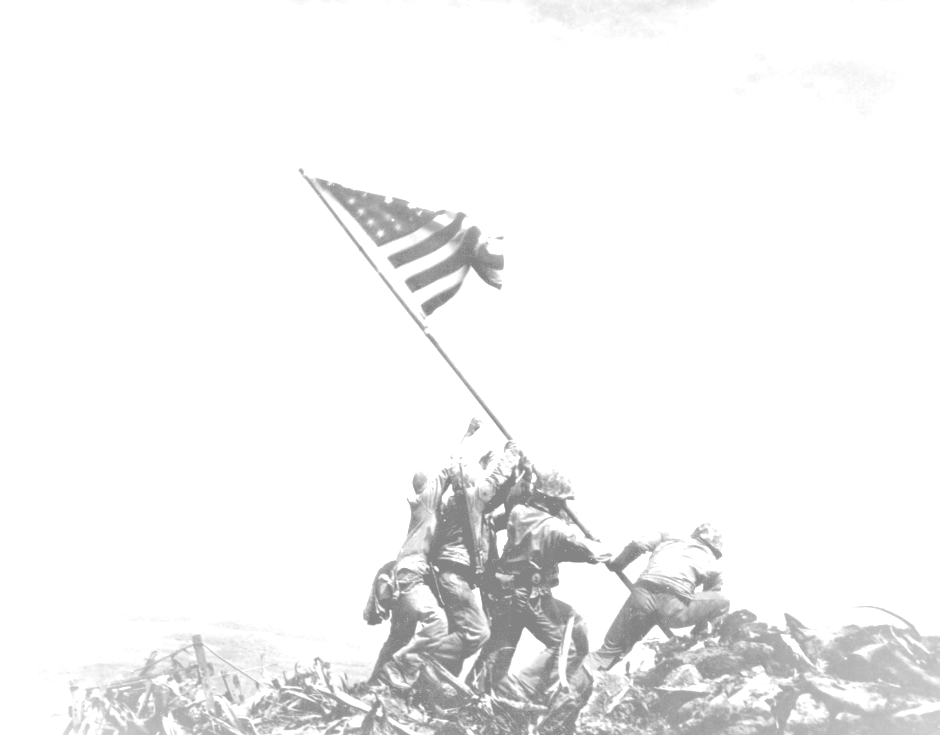

On the fifth day of the 36-day battle, a band of American soldiers was assigned to plant the Stars and Stripes on top of Mt. Suribachi, the highest peak on Iwo Jima. As five marines and one navy corpsman carried out the task, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal caught the feat in his camera. It was, perhaps, the most iconic photograph of the war, earning Rosenthal the Pulitzer Prize.

Long after the war had ended, retired U.S. general Larry Snowden came up with the idea of bringing together the combatants from both sides annually. And so the Reunion of Honor was born.

Last March, more than 30 Americans and an unspecified number of Japanese combatants assembled on Iwo Jima for what may be the final ceremony of its kind. Among the attendees was Jerry Yellen, an aviator who hated the Japanese until his son married a Japanese woman.

The supreme irony is that the fighting on Iwo Jima, with its terrible death toll, may have been superfluous. After the United States dropped atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, thereby ending the war in the Pacific theater, Iwo Jima’s two airfields were no longer required.