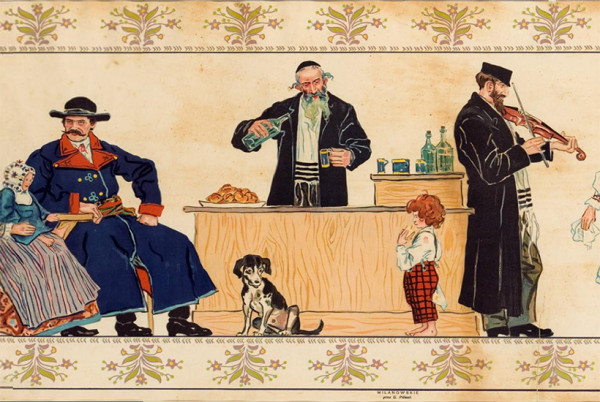

The Jewish-run tavern was an iconic feature of rural Poland for hundreds of years. “It was etched into the Polish landscape,” American scholar Glenn Dynner says.

These taverns, which existed until the late 19th century, were centers of leisure, business and life-cycle events, even after Poland lost its independence and was reduced to a partitioned entity under the yoke of foreign powers, said Dynner, a historian teaching at Sarah Lawrence College, a liberal arts institution in Yonkers, New York.

Jewish tavern keepers, the subject of Polish literature and folklore, played an integral role in local social life, noted Dynner, the author of Yankel’s Tavern: Jews, Liquor and Life in the Kingdom of Poland.

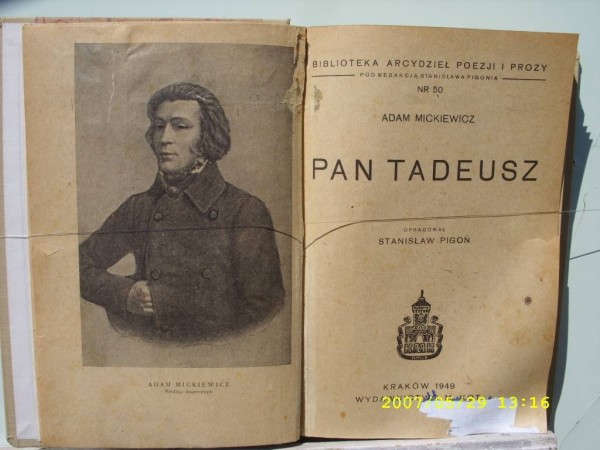

The title of his book is derived from an epic poem, Pan Tadeusz, written by the great Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz. Citing the Jewish tavern keeper Yankel, he claimed that his establishment summoned up quintessential Jewish visions: “From a distance the rickety old tavern looked / like a Jew rocking in prayer / the roof like a hat, the thatch spilling down like a beard / the sooty walls like a gabardine / in front, carvings protruding like tzitzit down his body.”

From the era of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth on down, Jews leased taverns and distilleries from the Polish nobility. This symbiotic relationship fostered a spirit of amity, which is often forgotten today, said Dynner, speaking at the University of Toronto’s Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies on February 22.

During this period of robust Jewish-Christian coexistence, three-quarters of the world’s Jewish population was concentrated in Polish lands, where Jews secured a safe and prosperous existence, he noted.

Jews drifted into the liquor trade due to a confluence of circumstances.

Eastern Europe, a regional breadbasket, was a net exporter of grain until Prussia, Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire seized Polish territory in the partitions of 1772, 1793 and 1795. Until then, surplus grain had been converted into vodka, which peasants consumed in prodigious quantities at taverns owned by Polish nobles and managed by Jews.

With the drastic decline of grain exports following Poland’s disappearance as a sovereign state, the liquor trade became the most lucrative industry in what would be the Pale of Settlement, the area where the vast majority of Polish Jews in the Russian Empire were forced to live.

In an oft-repeated pattern, Polish nobles invariably leased distilleries and taverns to Jews because they were perceived to be sober and industrious. Jewish sobriety was an asset that Polish landowners valued and grudgingly respected, said Dynner.

Taverns run by Jews, frequented by the peasantry and itinerant Jewish merchants, were the venues of ceremonies celebrating or marking births, marriages and deaths.

Since an alarming number of peasants succumbed to alcohol addiction, social reformers and antisemites alike demanded the expulsion of Jews from the liquor trade, thereby imperilling Jewish tavern keepers. In short order, the authorities levied exhorbitant taxes on them, but the tactic failed.

Supported by Polish nobles, who had a lot to lose financially if Jewish tavern keepers were driven out of business, Jews either hired Christians to manage the taverns or operated them underground.

This arrangement persisted until about the 1870s, reflecting an impressive level of local coexistence that contrasts with the more familiar story of antisemitism in Poland, said Dynner.

With the emancipation of the Russian peasantry in the 186os, Christians gradually supplanted Jewish tavern keepers, closing a unique epoch in Eastern European history.

But as Dynner pointed out, the association of Jews with liquor never really ended because the region’s drinking culture encompassed Hassidic Jews, a topic he explores in another book, Men of Silk:The Hassidic Conquest of Polish Jewish Society.

Rebbes condoned controlled recreational drinking to usher in major religious holidays and events like births, bar mitzvahs and marriages. But they disapproved of excessive drinking, and their followers faithfully obeyed their edicts.