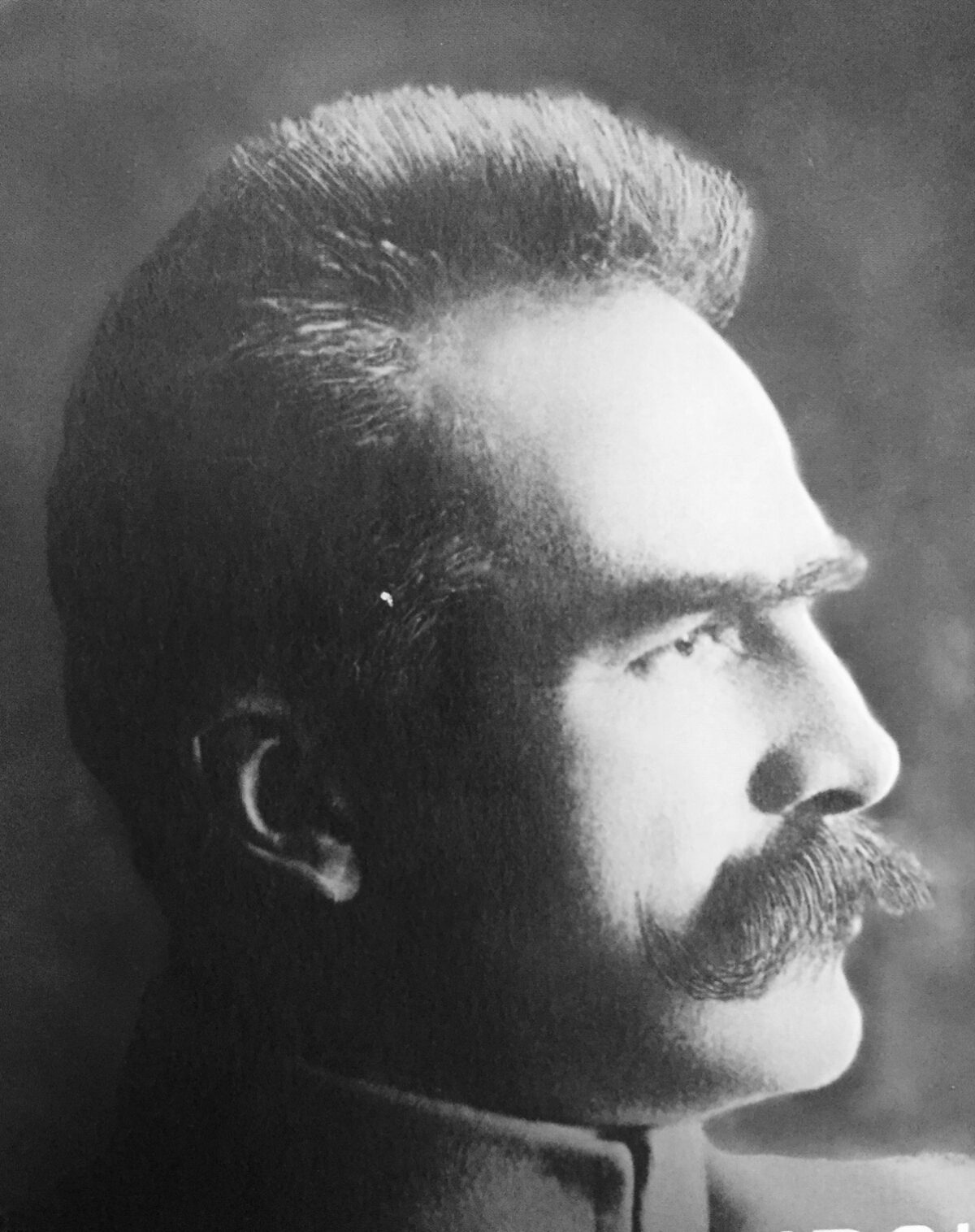

Jozef Klemens Pilsudski, the dominant personality in Polish politics from 1918 to 1935, was surely one of the most remarkable figures of the 20th century.

Revered as the creator of a reborn Poland in the wake of World War I, he was loved and admired by most Poles, particularly Polish Jews. During the communist interregnum, however, he was reviled as a bourgeois dictator and banished from public memory. Since Poland’s emergence as a democratic state, he has been rediscovered and recognized yet again as a national hero.

Streets, squares and parks have been named after him. Monuments in his honor have arisen. Academic conferences and government declarations have paid tribute to him. A mid-1990s survey of the 100 most influential Poles in history ranked him second only behind Piast, Poland’s first ruling monarch.

Pilsudski was a great, though flawed, person, as the distinguished American historian Joshua Zimmerman argues in his magisterial biography, Jozef Pilsudski: Founding Father Of Modern Poland, published by Harvard University Press.

“In this book, I portray Pilsudski’s dual legacy of authoritarianism and pluralism. He was a military leader who used extra-legal, strong-arm tactics to suppress his opponents while safeguarding minority rights. He … marched against the broader trends of totalitarianism and antisemitism taking root in Central and Eastern Europe between the two world wars … he believed in a pluralistic society where law-abiding citizens received equal treatment and protection.”

During the last nine years of his rule, on the other hand, he staged a coup and cracked down on the parliamentary democratic system he had methodically devised. Pilsudski resorted to this drastic action because he was frustrated by his inability to pass constitutional reform through the Sejm, adds Zimmerman, a Yeshiva University scholar whose last book was The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939-1945. Having transformed Poland into an authoritarian state, he “abandoned the principle of democracy as freedom bound by the rule of law,” writes Zimmerman.

A man of all seasons, Pilsudski was Poland’s first head of state, the commander of its armed forces, and the strategist who led Poland to victory over Bolshevik Russia in the 1920 war. This conflict settled Poland’s eastern border and cast Poland into the role as a bulwark against the spread of communism in Europe.

By signing non-aggression pacts with the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in the early 1930s, Pilsudski kept the peace in Europe for a while longer, though he had no illusions about their rapacious territorial designs on Poland.

He regarded Poland as a tolerant multinational, multilingual and multicultural state along the lines of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Unlike right-wing nationalists and racists like Roman Dmowski, he believed that its Jewish, German, Ukrainian, Tatar and Belarusian minorities were an integral component of Poland’s cultural heritage. As Zimmerman notes, he kept extreme antisemites in check and welcomed the participation of Jews in his government.

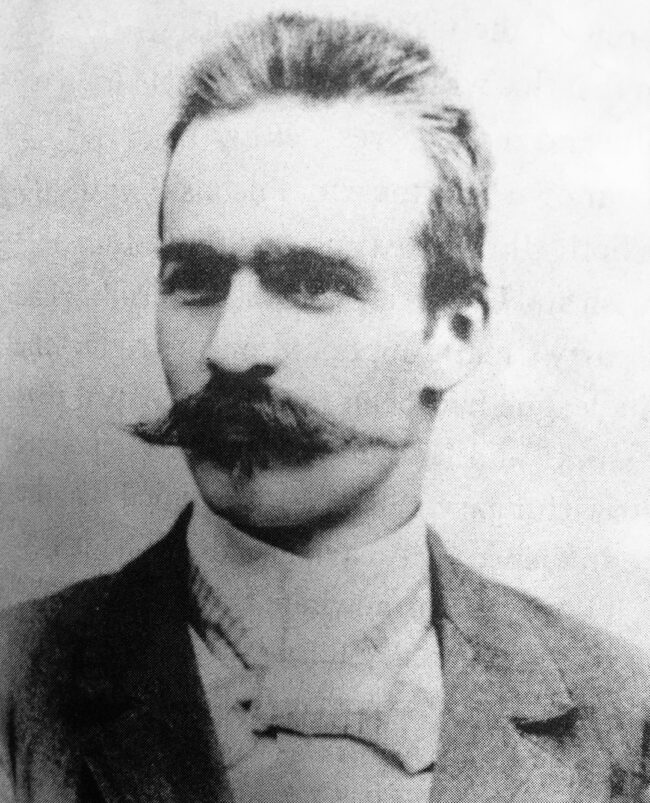

Born in 1867 in the village of Zulow, near Vilna, he was the fourth child of parents from the Polish-Lithuanian landed gentry. Raised on an estate surrounded by forests, fields and meadows, he had an idyllic childhood.

Poland had lost its sovereignty and independence to Russia, Prussia and the Austro-Hungarian empire in three separate partitions, but rebellion stirred in the hearts of Polish nationalists. Pilsudski was brought up in stories of the 1863 uprising, and he later spoke of its centrality in his thinking.

His family, following the devastating loss of its fortune, moved to Vilna in 1875. By then, 45 percent of its 77,000 inhabitants were Jewish. Yet Vilna remained a powerful symbol of Polish culture.

During his youth, he and his brother, Bronislaw, were arrested by the authorities for anti-Russian agitation. Both were exiled to Siberia, and it was there that Pilsedski spent the next few years on a prison island on the Lena River. During his imprisonment, he met and came under the influence of Stanislaw Landy, a socialist from an acculturated Jewish family whose ancestors had supported Poland’s quest for renewed statehood. There, too, he met Landy’s sister, Leonarda, an anti-government activist and Pilsudski’s first love.

In the next phase of his career, Pilsudski assumed the leadership of the Polish Socialist Party. Feliks Perl, a Polish Jew, became one of his closest collaborators. Relentlessly ambitious, Pilsudski strove to form ties with the emerging Jewish and Lithuanian socialist movements, promoted the idea of a resurrected Poland, and worked to establish a Yiddish newspaper for his Jewish compatriots in Vilna. He assured them that the Jewish proletariat would have a strong ally among class-conscious Polish workers.

Bt the late 1890s, Pilsudski, a gifted organizer and a formidable writer who could inspire loyalty, had developed a kind of legendary status, not only as a politician but as a military commander who had poured his energy into building and training a Polish armed force for eventual combat with Russia.

Although he was averse to racial prejudice, Pilsudski could be verbally derogatory in private when referring to Jews or ethnic Russians in rival political parties. Yet in his first article in a socialist periodical devoted to Jews, he condemned antisemitism as an injustice and backward current and promised that any trace of it among his comrades would be persistently fought.

Pilsudski, in his appeals, tried to bring more Jews into the party and urged Polish and Jewish workers to unite in a common struggle under a single banner to liberate Poland from the yoke of foreign domination.

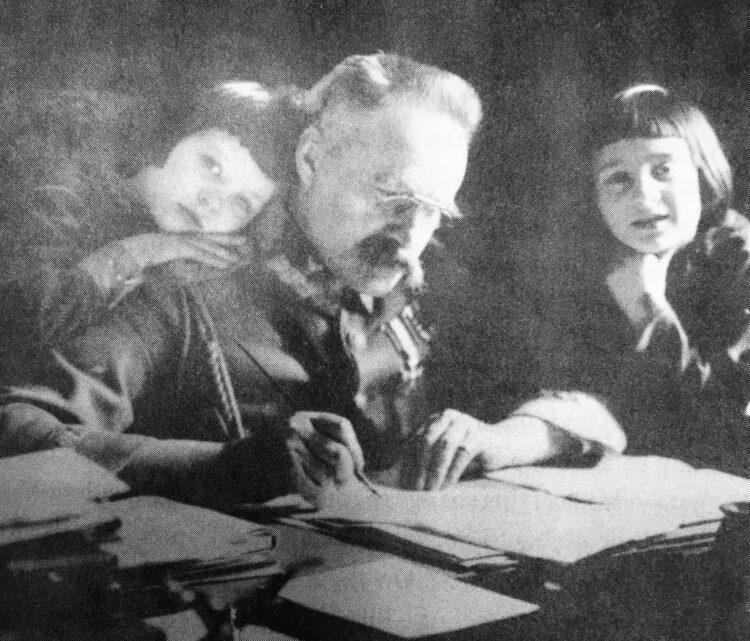

A Roman Catholic, he converted to Protestantism in 1899 to marry his first wife, a divorced Polish woman. His second wife bore him two daughters, Wanda and Jadwiga, to whom he was extremely attached.

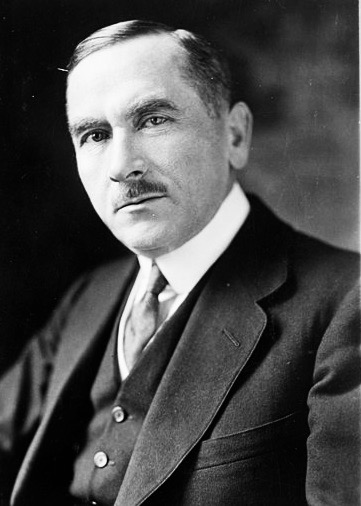

Until Pilsudski’s death, one of his chief rivals was Roman Dmowski, the leader of the far right-wing National Democratic Party and a vicious antisemite who would never moderate or renounce his toxic view of Jews. With support from conservative Polish landowners, industrialists and clergy, Dmowski formed the Polish National Committee, which sought Polish nationhood. Following the outbreak of World War I, Dmowski aligned himself with Western countries, while Pilsudski sided with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire.

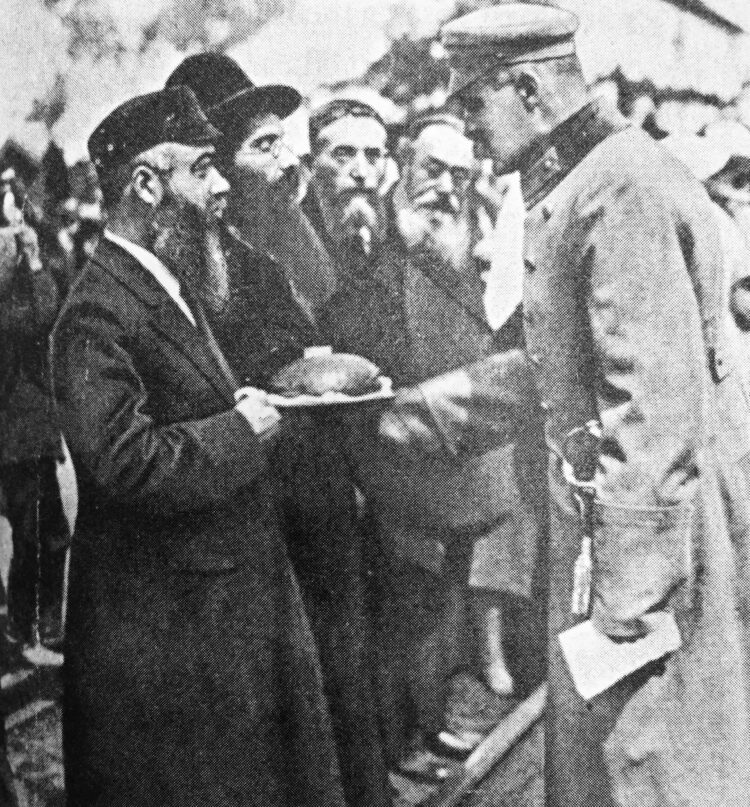

Pilsudski’s gamble paid off when a combined German-Austrian offensive liberated what had been the Kingdom of Poland from Russian control and when the new provisional government in post-czarist Russia endorsed the formation of a Polish state. Pilsudski formed Polish fighting units, to which Jewish volunteers flocked after promises of equality in a future Poland. In 1917, Pilsudski was arrested after he and the Germans had a falling out. He spent many months of captivity in Germany, and was released in November 1918.

With 80,000 German troops having withdrawn from the Kingdom of Poland, an armistice was declared, and the Regency Council, the de facto ruling authority, asked Pilsudski to take command of the armed forces and entrusted him to form a unity government. By this point, he described himself as a “democrat” rather than as a “socialist.”

Yet on the day Poland was resurrected as a nation, in the form of the Second Polish Republic, rival centers of authority still existed in Krakow, Poznan and Lublin, while the Polish National Committee, based in Paris, claimed to represent Poland and disseminated lies that Pilsudski was a Bolshevik. Pilsudski, a potent symbol of national unity, managed to unite these factions under his strong and charismatic leadership.

As well, he invited the leaders of Jewish political parties, including the Jewish Labor Bund and the Labor Zionist Party, to the second round of talks aimed at forming a government, and pledged to defend the rights of all “citizens” rather than “Poles.” This promise reflected his commitment to equality for all Poles, regardless of religion. One of his key aides reiterated this pledge: “In the field of equal civil rights, Poland shall inherit the most glorious tradition of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.”

In juxtaposition to this highflown rhetoric, pogroms broke out in Lwow, Kielce and numerous other localities within days of Poland’s attainment of nationhood. Polish soldiers participated in these attacks. “The spread of anti-Jewish violence tarnished Poland’s image at the very moment of its rebirth,” notes Zimmerman, who quotes a Jewish observer as saying that “the birth of Poland was accompanied by rivers of blood.”

Pilsudski addressed the crisis by receiving two Jewish delegations. Attributing the pogroms to the breakdown of law and order, he acknowledged that his government did not yet possess the means to halt every pogrom. His Jewish interlocutors were disappointed by his sterile reaction. A British Jewish leader who met Pilsudski shortly afterward reported that he candidly admitted that “the Poles were no philo-Semites.”

As Zimmerman observes, the 340 deputies in Poland’s first elected assembly were divided along partisan lines, with 34 percent of the seats going to rightists, 30 percent to centrists and 30 percent to leftists.

The first complete Polish census, issued in 1921, showed that while ethnic Poles comprised almost 70 percent of the population, Ukrainians (14.3 percent), Jews (7.8 percent), Germans (3.9 percent) and Belarusians (3.9 percent) accounted for much of the rest of Poland’s citizens.

The United States championed Polish independence, and under the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, it became the first country in the Western alliance to establish formal diplomatic relations with Poland. France, Britain and Italy followed suit.

Having won recognition from the major powers, Pilsudski turned his attention to the settlement of Poland’s frontiers. He assumed that the western border with Germany would be largely imposed at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, but he knew that Poland’s eastern border with the Soviet Union would be determined only by military means. He was right. Poland lost 4,500 troops in its battles with the Red Army.

During the course of the war, Poland’s minister of war issued a notorious order to intern Jewish soldiers, officers and volunteers at a camp in the town of Jablonna. He claimed he acted in the interest of stopping “the harmful activities of the Jewish element” in the Polish army. There is no evidence that Pilsudski instructed him to do this. Neither is there any record that he objected to it. But as Zimmerman points out, the minister would not have issued this order without Pilsudski’s approval.

The Treaty of Riga, signed on March 18, 1921, formally ended Poland’s war with the Soviet Union. Under its terms, Moscow recognized Polish sovereignty over the Vilna area, East Galicia, western Belarus and western Volhynia. In exchange, Poland recognized Russian control over the eastern Belarusian and Ukrainian borderlands. This was a geopolitical blow to Pilsudski, who had said, “There can be no independent Poland without an independent Ukraine.”

Pilsudski’s choice for president, Gabriel Narutowicz, defeated four other candidates. On December 16, 1922, five days after being sworn in, he was assassinated by a painter who sympathized with the National Democratic Party. The assassin insisted that Narutowicz had been elected not by a majority of ethnic Poles but by the national minorities, especially Jews. Pilsudski’s adversaries taunted him by referring to Narutowicz as “Mr. Narutowicz, President of the Jews.”

Profoundly disillusioned by this ugly turn of events, Pilsudski withdrew from public life in 1923. But in 1926, after a new government of right-wing populists and nationalists was named, led by the leaders of who had attempted to delegitimize Narutowicz, Pilsudski decided to intervene. Believing he was acting in Poland’s best interests at a moment when it had fallen into a fiscal and political crisis, he ordered the president to dissolve the government. After three days of street battles, which claimed the lives of some 400 soldiers and civilians, he seized absolute power.

“The coup shook the country to its core,” says Zimmerman. “In the most undemocratic of ways, Pilsudski removed the government by force.” While he did not impose a dictatorship, he reduced the powers of parliament and increased his own substantially in his “Sanacja” (healing) regime.

While he regained power with the support of the left, he felt he could only stabilize Poland by recruiting certain landowning aristocrats from the eastern borderlands into his government. “One of his goals was to draw them away from the National Democrats,” says Zimmerman.

His leftist colleagues were disenchanted with his maneuver, claiming he had placed “monarchist and reactionary” elements in the government.

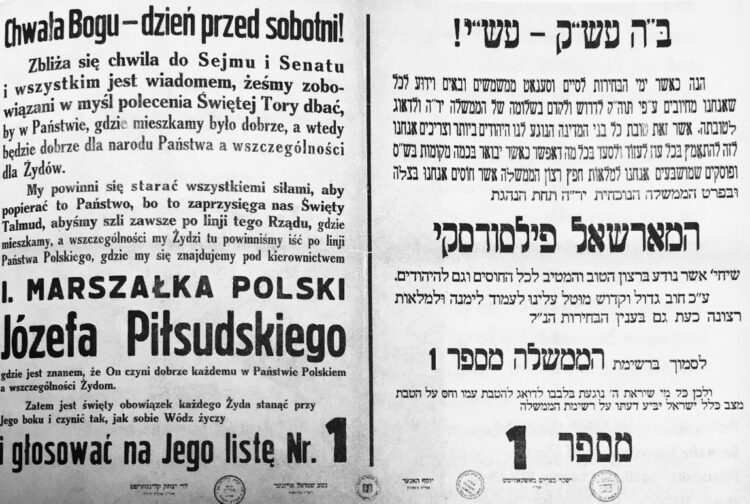

Ethnic Germans and Jews supported Pilsudski’s coup. As the Jewish historian Szymon Rudnicki wrote, “For Jews, (it) meant the end of the extreme nationalist authorities of the hated nationalist camp for whom the struggle with the Jews was a staple part of their program.”

Soon after the coup, the Polish government took a series of steps to improve the position of Jews. The minister of education denounced the numerous clausus in education and banned it in institutions of higher learning. The right to use Yiddish in public places was guaranteed. Thirty three thousand Russian Jews who had immigrated to Poland after 1917 were granted citizenship. Kazimierz Bartel, a liberal and an opponent of antisemitism, was appointed prime minister.

Pilsudski’s government, in addition, stood firmly opposed to anti-Jewish bills sponsored by the National Democrats and their allies.

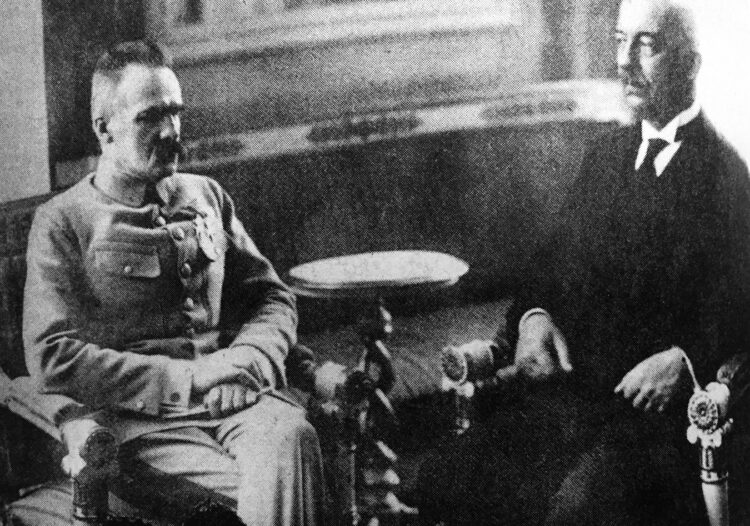

In the meantime, Pilsudski moved forward to implement his policy of “equilibrium” in foreign affairs, which called for concluding peace treaties with two of Poland’s enemies — Germany and Soviet Russia. He signed non-aggression pacts with the Soviet Union in 1932 and with Germany in 1934 after deciding that France, his oldest ally, would not offer a military guarantee of Poland’s borders. Being a realist, Pilsudski thought that the treaty with Germany would not last for more than a few years and that another war would break out due to the unresolved Danzig corridor problem. As a result, he regarded Poland’s alliance with France as the key to its security.

Shortly after Poland signed the non-aggression agreement with Germany, Polish Foreign Minister Jozef Beck announced that it was pulling out of the 1919 Minorities Treaty. He and Pilsudski claimed that the legal status of minority groups in Poland would not be compromised, saying that the constitution guaranteed minority rights. Jewish leaders abroad rejected this explanation, but Polish Jews seemed less concerned.

Around this time, as Pilsudski’s health deteriorated markedly, the Polish government passed a new constitution. It effectively gutted parliamentary democracy, but retained guarantees of civil liberties and religious freedom, and preserved the rights of opposition parties.

In April 1935, Pilsudski was diagnosed with advanced, incurable cancer of the liver, though he remained cognitively lucid. British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden was one of the last foreigners to see him and, in a cable to London, he reported that Pilsudski’s mind was failing and that he was physically very feeble.

Pilsudski died on May 12 of that year at the age of 67. His death shocked the nation to its core. He was buried in Krakow’s Wawel Castle, his coffin lowered into a crypt alongside the tombs of Polish greats such as King Jan Sobieski and Tadeusz Kosciusko.

Catholic Poles were bitterly divided over his legacy, but Jews mourned his passing as a friend of the Jewish community. Pilsudski’s death was followed by a wave of pogroms in 1935, the first unfolding in Grodno. Antisemitic violence continued through 1936 and 1937 in 100 incidents that led to the deaths of 17 Jews.

“In addition, Pilsudski’s heirs moved the country increasingly toward a politics resembling that of his enemies, the National Democrats,” writes Zimmerman. “This included the imposition of repressive measures on minorities … to limit their rights, to pressure Jews to emigrate, and to allow so-called ghetto benches in Polish universities.”

As for Beck, he steered Poland toward a more pro-German orientation, being confident that Germany would honor the non-aggression pact.

Poland, cursed by its geography, did not properly prepare for the war that Pilsudski had so presciently predicted.

Zimmerman, in his splendid book, paints a balanced and thoughtful portrait of an eminent Polish leader who devoted body and soul to reestablishing a state that had been swept away by the tides of fate.