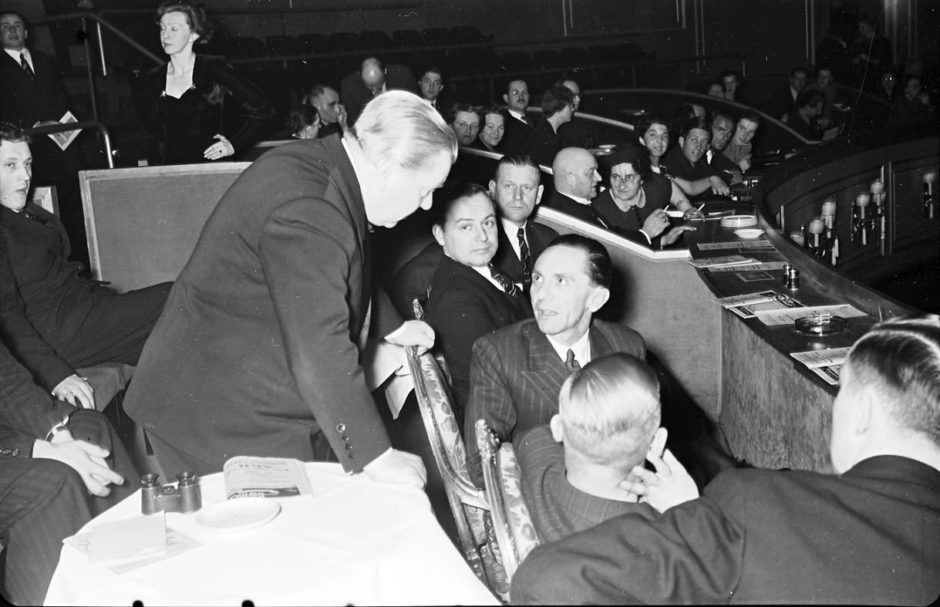

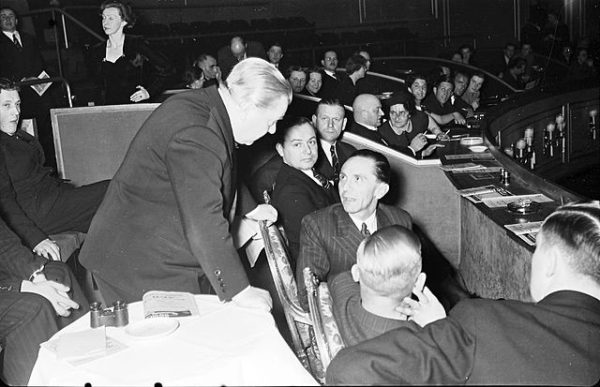

Film is a powerful tool in mobilizing public opinion in support of a cause or idea. Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Germany’s rabidly antisemitic propaganda minister, instinctively understood this principle as he launched campaigns to marginalize and demonize German Jews.

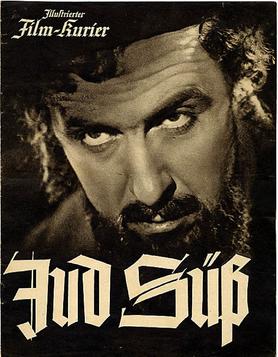

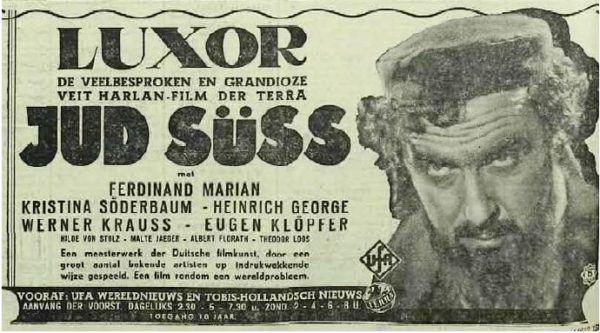

As commissar of the German movie industry, Goebbels had the authority to commission films. Three of them — Die Rothschilds (The Rothschilds), Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) and Jud Suss (Jew Suss) — are widely considered to be among the most ignoble and despicable films in the history of cinema.

Released in 1940, they were intended to portray Jews in the worst possible light, as conniving hucksters and incorrigible enemies of Germany. Having seen the first two movies some years ago, I wanted to watch Jud Suss. I found it on YouTube, free of charge.

Shot in Prague and Berlin, it was directed by Veit Harlan, who was supposedly pressured into accepting the assignment. In 1954, he admitted he was “deeply ashamed” of his involvement in it and burned his negative.

First screened at the Venice Film Festival on September 8, 1940, Jud Suss garnered rave reviews and attained cult status as one of the most popular films of the Nazi epoch. Goebbels was certainly pleased by its production values and its success in conveying or reinforcing negative perceptions and myths about Jews. Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, was so impressed that he encouraged SS personnel to watch it.

Jud Suss was adapted from Wilhelm Hauff’s 1837 novella of the same name. Lion Feuchtwanger, the German Jewish writer, wrote a similarly titled novel in 1925 based on his 1916 play.

Jud Suss revolves around Joseph Suss Oppenheimer (1698-1738), a court Jew in the employ of Duke Karl Alexander of Wurttemberg in Stuttgart. A wealthy banker, he acquired a degree of influence in Karl Alexander’s duchy that earned him widespread enmity.

No sooner had his sponsor and protector died than his Christian enemies pounced, charging him with a raft of crimes ranging from immorality to high treason. Offered relief from execution if he converted to Christianity, Oppenheimer adamantly refused, and was hanged.

Goebbels seized on Oppenheimer as a stock figure who could be reviled by the masses. But he instructed the film’s screenwriters, Ludwig Metzger and Eberhard Wolfgang Moller, to omit references to conversion. Dedicated to propagating and enforcing racial antisemitism, the Nazis had nothing but contempt for Jews who had embraced the Christian faith. As far as they were concerned, Jews were racially impure and could never be real and proper Germans.

Oppenheimer is played by Ferdinand Marian, whose first wife was Jewish. Interestingly enough, he initially resisted Goebbels’ offer of playing the lead role. It took Goebbels about a year to convince him to change his mind.

The plot is straightforward.

Karl Alexander sends an emissary to Oppenheimer’s home in Frankfurt’s ghetto to secure a loan. Oppenheimer, in an ostentatious show of wealth, opens a drawer sparkling with exquisite jewellery.

Oppenheimer is required to visit the duke’s castle in Stuttgart to seal the deal. He assures his interlocutor he’ll conceal his Jewish appearance by shaving off his beard and shedding his caftan. As he plans his trip to Stuttgart, to which Jews are forbidden, the duke’s governing council rejects his demand for a budget to cover the cost of a ballet, opera and bodyguard.

En route to Stuttgart, Oppenheimer has a road accident and meets Dorothea (the Swedish-born actress Kristina Soderbaum, who was married to Harlan). Dorothea is blonde, blue-eyed and beautiful, the perfect Aryan woman. As they chat, he tells her he’s a world traveller who feels at ease “everywhere” and considers the world to be his “home.” By Nazi standards, he’s a rootless, selfish cosmopolitan, loyal to no nation.

Oppenheimer strikes an agreement with the duke (Heinrich George, a member of the German Communist Party before the rise of Nazism). Stocky and hedonistic, the duke is depicted as a spendthrift in thrall to a scheming, grasping and untrustworthy Jewish financier. Much to his shock, the duke discovers he’s deeply in debt to Oppenheimer.

No problem, chortles Oppenheimer. He’ll retire his debt if he gives him control of toll roads and bridges. As expected, farmers complain bitterly about the sharp increase in tolls. Passing on their extra costs to the common folk, they create a climate of anger and insurrection.

Oppenheimer, of course, is blamed for the crisis. A procession of cardboard characters excoriate Oppenheimer. Sturm (Eugen Klopfer), the duke’s advisor and Dorothea’s father, observes that “the Jew” is not smart, only cunning. Faber (Malte Jaeger), Dorothea’s fiancee, accuses him of corruption. A blacksmith claims he’s fleecing the people.

Despite the discontent, the duke lifts the prohibition banning Jews from Stuttgart. The council, supposedly the voice of the people, is in an uproar and demands the restoration of the ban. Paraphrasing the antisemitic theologian Martin Luther, a councilman warns the duke he has no worse enemy than the Jews. Oppenheimer advises him to dissolve the council and appoint a new and pliable one.

At this juncture, the rabbi shows up. Stereotypical in appearance, with an off-putting whining voice, he’s played by Werner Krauss, a staunch antisemite who belonged to the Nazi Party despite having a Jewish daughter-in-law.

Emboldened by his growing power, Oppenheimer asks Sturm for the hand of Dorothea in marriage. In an indignant rage, Sturm exclaims, “My daughter will bring no Jewish children into the world.”

Sturm, having accused Oppenheimer of alienating the duke from his subjects, is promptly arrested. The duke dissolves the council, but soon turns against Oppenheimer. “Nothing is sacred to you, only your interests,” he declares, mouthing a common Nazi theme.

With an uprising having begun, the scene shifts to a crowded synagogue, where Jews, played by Jewish extras, hatch a plot to confer absolute powers on the duke. Faber claims the Jews are financing a civil war for their own ends. The duke, having already distanced himself from Oppenheimer, calls him a swine and categorically rejects his suggestion that the uprising can be crushed by violent means.

Amid the disorder, Faber is arrested on Oppenheimer’s orders and tortured. Meanwhile, in a scene laden with a vicious anti-Jewish trope, Oppenheimer ravishes Dorothea, the lovely German maiden.

“The Jew must go!” shouts a man after Dorothea’s lifeless body is found.

When death suddenly strikes the duke, Oppenheimer is detained, charged with a litany of crimes and put on trial. “I’m just a poor Jew,” he wails, defending himself in a kangaroo court.

The film ends on a full-throated note as an outraged burgher declares that every Jew must leave Wurttemberg and that none of their descendants may ever return. It’s a clarion call for ethnic cleansing, a Judenrein Germany, the policy advocated by the Nazis.

After Germany’s surrender in 1945, the Allies banned Jud Suss in Germany. The ban is still in effect. Harlan was charged with crimes against humanity, but was acquitted. The lead actors were temporarily blackballed, but regained their footing eventually. Marian was killed in a car accident in 1946. George died in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp after being branded as a Nazi.

Today, Jud Suss is little more than a cinematic curiosity, but its power to sow contempt and hatred and inspire genocide still chills the blood.