The rise and fall of a major American racist is the subject of Klansville, U.S.A, a searing documentary to be broadcast by the PBS television network on Tuesday, Jan. 13 at 9 p.m as part of its American Experience series. It’s the story of Bob Jones, the grand dragon, or leader, of the United Klans of America, a Ku Klux Klan splinter group that battled in vain to uphold segregation.

Jones, a high school dropout and the son of a railway worker, was the most successful grand dragon in the United States, having amassed a membership of 10,000.

Jones, whose father was a klansman in the 1920s, pushed back against the tide of desegregation and fought the civil rights movement in North Carolina, considered the most progressive state in the South in the 1960s.

A beacon of the New South, North Carolina diverged from militant states like Mississippi and Alabama, accepting gradual change in race relations and refraining from challenging the federal government’s policy of abolishing the racial status quo. Neither civil rights activists nor white bigots embraced North Carolina’s gradualist approach.

Jones, who denied he was a racist, appealed to poor whites who feared that integration and the end of the Jim Crow era would threaten their livelihood and way of life. Claiming he was fighting to protect his constituents, he glibly compared his organization to the B’nai Brith and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

“We had the NAACP, and they had the Klan,” says an African American woman.

Klansville, U.S.A., based on a book by David Cunningham, gives viewers a rounded portrait of Jones and the Ku Klux Klan, which was born in Pulaski, Tennessee, the wake of the Civil War. Formed to terrorize free slaves, the Klan turned increasingly violent during the Reconstructionist period, prompting the federal government to clamp down on it.

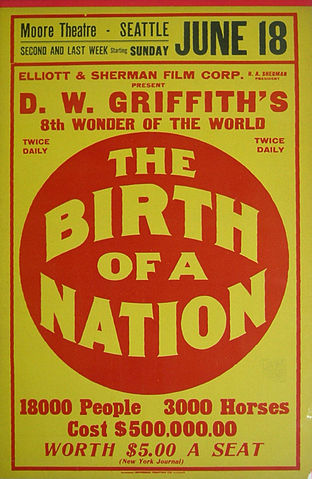

D.W. Griffith’s silent 1915 film, Birth of a Nation, sparked a revival of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, when it reached its apogee of influence. Griffith glorified Klan violence and romanticized its white supremacist message. In 1925, when the Ku Klux Klan had about four million members and sympathizers in high political offices throughout the United States, 50,000 Klansmen in full regalia marched toward Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. in a show of force.

Due to internal power struggles and scandals, the Klan declined from the 1930s onward, not to rise again until the mid 1950s, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in a historic verdict, that American schools should be desegregated.

Watching these events from afar with a growing sense of unease and dismay, Jones established the United Klans of America. He feared that North Carolina would not stand up to the civil rights movement or the federal government.

Rather than admit to being a racist, he claimed he merely sought separation from African Americans. If nothing else, Jones was disengenuous. He was booted out of the navy after refusing to salute a black naval officer, and he built an empire grounded in hate-filled rhetoric.

Jones, who promoted non-violence to achieve his goals, launched a recruitment drive in the early 1960s, using his organizational skills to stage rallies, cross burnings and “street walks” across North Carolina. New recruits sought “status in the community,” and he gave it to them, an ex-member says.

Lambasting desegregation as an abomination, Jones strove to convert his fraternal organization into an electoral force to help “real white people.”

The murder of a white civil rights worker prompted the U.S. president, Lyndon Johnson, to order a crackdown on the Klan. Within this framework, Jones committed his first mistake by inviting the three suspects who may have killed that person to a rally. A TV crew filmed the event, calling into question Jones’ commitment to non-violence.

At this point, Jones’ assistant, George Dorsett — a Baptist minister — turned traitor, becoming an FBI informant. Like some of Jones’ acolytes, he had reached the unsettling conclusion that Jones was guilty of financial irregularities. Jones also lost support after declining to testify before the U.S. Congress. In 1969, he was sentenced to a year in prison for having refused to comply with an order to hand over documents to the federal government.

By then, the United Klans of America had virtually imploded, with many members having drifted into the arms of the Republican Party and the fiery governor of Alabama, George Wallace, who had once declared, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever.”

Jones had had his day in the sun, his 15 fleeting minutes of fame.