Most Jews in Russia after the 1917 communist revolution were anti-Bolshevik. But within two years of that historic upheaval, which transformed tsarist Russia into the Soviet Union, the majority of Russian Jews had flocked into the Bolshevik camp.

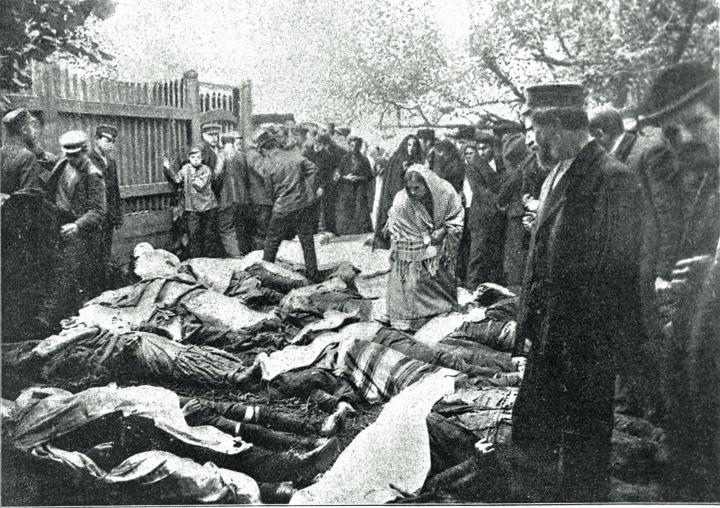

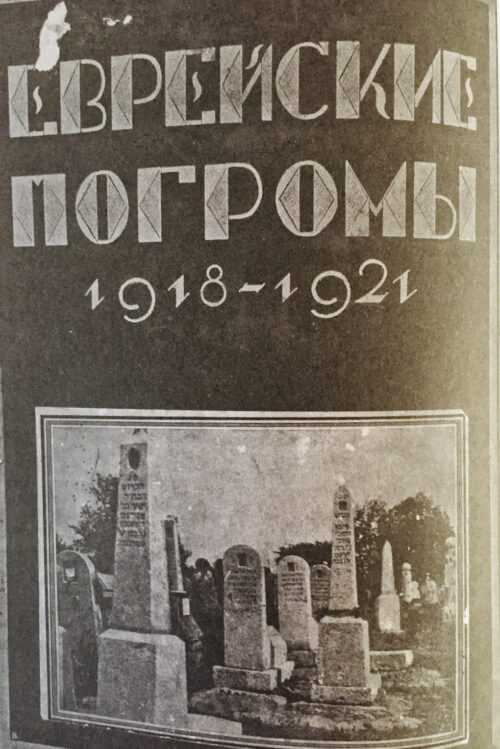

At the root of this transformation were the 1,500 pogroms unleashed by the Russian civil war from 1918 onward. They claimed the lives of about 150,000 Jews and orphaned 300,000 children.

The new Soviet government denounced antisemitism and condemned pogroms and blood libels, which were inextricably associated with the old Romanov dynasty.

By contrast, the forces hostile to Bolshevism were intrinsically antisemitic. They stirred up mass violence against Jews in the form of pogroms. They perpetuated the myth that Jews murdered Christian children so as to ritually use their blood to bake matzah during Passover. And they promoted the Judeo-Bolshevik falsehood that Soviet communism was really part of a wider Jewish scheme to seize power.

As a result, writes Elissa Bemporad in her excellent book, Legacy of Blood: Jews, Pogroms, and Ritual Murder in the Lands of the Soviets (Oxford University Press), Jews forged a pragmatic alliance with the nascent Soviet state.

The Soviet Union, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s, claimed to have eradicated these expressions of antisemitism, but in fact they enjoyed something of an afterlife in the communist utopia and beyond, says Bemporad, a Queens college professor of history.

The decision by Jews to support the Soviet Union would have profound consequences. “It bolstered the idea of a Jewish propensity for communism,” she notes. “The Bolsheviks’ validation of the legal emancipation of Jews, which allowed them to join the political system, and participate in the newly established socialist society without quotas or discrimination, further encouraged this notion. In the eyes of many Soviet citizens, the state was complicit in consenting to the unnatural and incomprehensible rise of Jews to new socio-economic positions of power, of visibility, of responsibility.”

Jews came to be seen as agents and proxies of communist rule, a perception which played into the widespread claim of Judeo-Bolshevism, Bemporad adds. To such Russians, antisemitism was a “defence strategy” against Sovietization and the communist regime itself. In such circles, the czarist slogan “Beat the Yids and save Russia” was endemic.

The pre-revolutionary pogroms of 1881-1882 and 1903-1906 were different from those that occurred during the civil war. The former were directly or indirectly orchestrated by the czarist regime, while the latter were carried out by anti-Bolshevik military forces, bands of hooligans and ordinary Russians who had once had peaceful, even friendly, relations with their Jewish neighbors. “In the imagination of many Russians, Poles and Ukrainians, Jews morphed into vectors for spreading communism,” she says, adding that Leon Trotsky, a leading figure in the Soviet pantheon, embodied this menacing specter.

Two of the most horrendous pogroms took place in the central Ukrainian shtetl of Dubovo and Fastov, where Jews and Ukrainians had generally lived in comparative harmony. These communities were virtually destroyed, destabilizing ties between Jews and Christians.

Red Army soldiers participated in pogroms, too, having been susceptible to stereotypes of Jews as capitalist exploiters of the downtrodden proletariat. “If the Red Army shared responsibility in the anti-Jewish violence, Soviet power was alone in condemning pogroms by their own forces and resisting targeting Jews for violence,” she says.

Sexual violence against Jewish women and girls was common, rape being deployed as a systematic weapon to enhance ethnic cleansing.

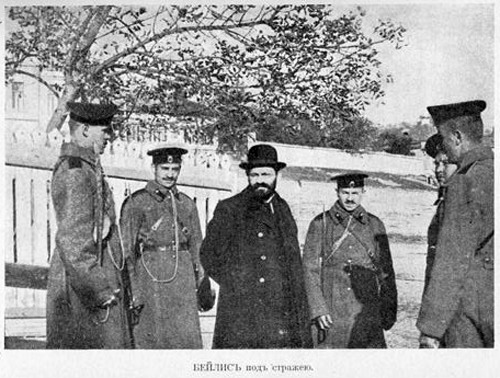

During the course of the civil war, the anti-Soviet White Army incorporated the blood libel myth into its antisemitic message. The Bolsheviks adopted a completely different policy. Shortly after the Red Army captured Kiev in 1918, Soviet authorities arrested and executed Vera Cheberiak, the criminal gang leader who had fabricated the notorious blood libel accusation against Mendel Beilis in 1911. Two czarist officials who had been involved in this travesty of justice, the minister of justice and the police chief, were also executed.

The regime’s campaign against the Russian Orthodox Church, a pillar of the czarist monarchy, validated suspicions that communists and Jews were allies. Tikhon, the patriarch of Moscow, claimed that “Yids” persecuted Christians and that “all members of the Communist party are Jewish.”

Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, having publicly condemned antisemitism in 1918, sanctioned the establishment of a special commission in 1919 to eradicate the legacy of blood libel, which he and his comrades regarded as the by-product of religious fanaticism embedded in the dark superstitions of the Middle Ages. Yet, as Bemporad notes, the official Soviet response to blood libel allegations fluctuated between condemnation and disregard.

She cites several cases, all of which surfaced in the mid-1920s in Dagestan and in the cities of Belyov and Poltava.

Throughout the 1920s, a rich literature about the pogroms, mostly in Yiddish, appeared in the Soviet Union. And although Soviet officials commonly equated the campaign against antisemitism with the struggle against chauvinism and “bourgeois nationalism,” they gradually distanced themselves from the former.

“Cultivating the public commemoration of anti-Jewish violence and systematically persecuting old crimes could intensify the resentment of those citizens who would otherwise become law-abiding Soviet citizens or even devoted Bolsheviks,” she explains.

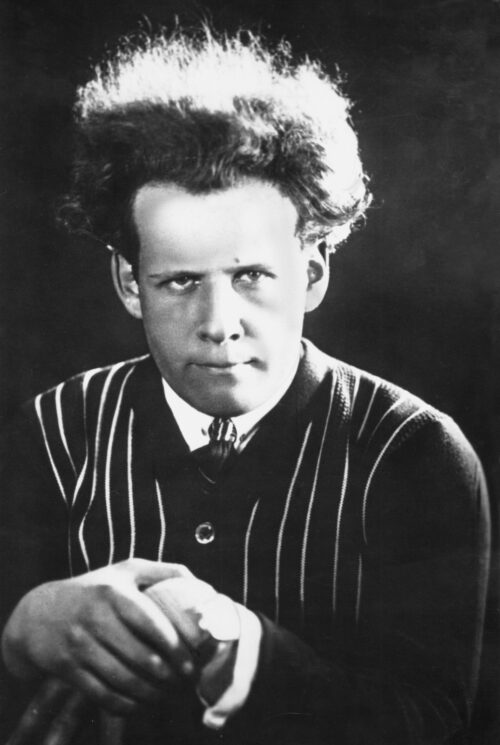

She provides a telling example. In 1940, the Soviet Committee on Cinema Affairs invited the great movie director Sergei Eisenstein to adapt Lev Sheinin’s play about the Beilis affair into a film. Soon enough, the production of the movie was halted, while the play itself was never performed.

Jewish-Ukrainian tensions escalated following the assassination of Ukrainian nationalist Simon Petliura in Paris in 1925. His Jewish assassin, Sholem Schwarzbard, blamed Petliura for the pogroms that had swept across Ukraine during the civil war. To Ukrainians, Schwarzbard confirmed their assumption that Jews and Bolshevism were synonymous.

So tense was the situation that antisemitic feelings bubbled to the surface in the Ukrainian cities of Kharkov and Odessa, with resentment emerging that Jews occupied the highest offices and that they had enslaved Russians.

“The desire to punish the Jews for their increased visibility in the economic and political sectors was remarkable,” she writes. “Not unlike the rage that took over the American South when blacks ‘refused to keep their heads down,’ these expressions of discontent and animosity stemmed also from a kind of nostalgia by antisemitic elements for the days when pogroms were real and Jews knew their place.”

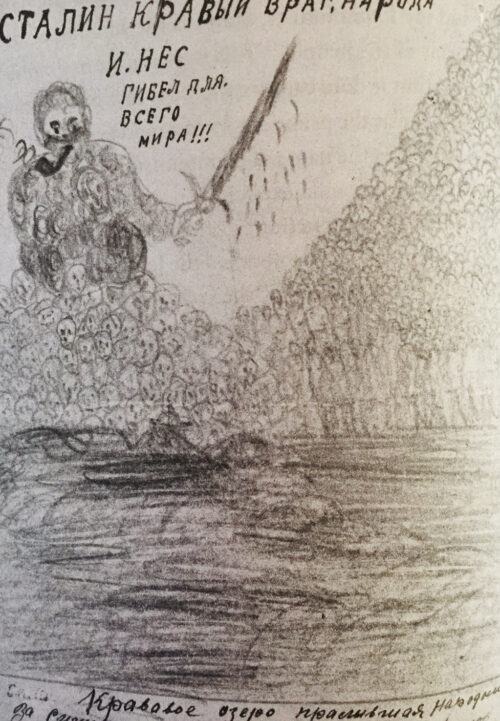

With Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, pogroms returned with a vengeance after Nazi propagandists revived the blood libel and Judeo-Bolshevik myths. “In many places, the local population came to see the German occupation as a ‘liberation’ from an overpowering Jewish-Bolshevism,” she says, singling out pogroms in Lvov, Rovno and Kiev. Jews were held accountable for (Joseph) Stalin’s crimes, including the Holodomor, the politically engineered famine in Ukraine in 1932 and 1933 that claimed the lives of about four million Ukrainian peasants.

Even as these pogroms erupted, the powers-that-be in Ukraine issued a secret directive to restrict the employment of Jews in prominent positions. When a loyal and reliable Jewish member of the Communist Party informed its first secretary, Nikita Khrushchev, that she had been denied a job due to her identity, he replied curtly: “Jews in the past committed many sins against the Ukrainian people. And the people hate them for this reason. Jews are not needed in our Ukraine.”

With Germany defeat, local perpetrators of pogroms were, in some instances, executed by the Soviet government. But in general, the authorities made the conscious decision to ignore and forget past atrocities in order to rebuild postwar society.

Antisemitism surged in the wake of the war. “The notion of Soviet universalism and ‘brotherhood of peoples’ seemed to reject the Jews,” says Bemporad. Antisemitism became “a widely employed and somewhat accepted cultural code.”

The Cold War, in combination with the birth of Israel, rendered Jews an unreliable and foreign element in the Soviet Union. Even Polina Zhemchuzhina, the wife of the Soviet foreign minister, Viacheslav Molotov, could not be trusted. In the autumn of 1948, she was sent to a gulag.

In 1953, in the infamous Doctors’ Plot, nine doctors, six of whom were Jews, were accused of murdering two Communist Party leaders. Ten years later, the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences published Trofim Kychko’s crassly antisemitic book, Judaism Without Embellishment.

Izvestia, an organ of the Communist Party, hailed it as as an important study on the reactionary nature of Judaism. Pravda, its competitor, warned it might encourage antisemitism. During this period, ten cases of ritual murder accusations were recorded in the Soviet Union, primarily in Lithuania, the Caucasus and Uzbekistan.

As Bemporad says, versions of the ritual murder myth persist to this day in Russia and Ukraine. In 2009, the Ukrainian writer Vyacheslav Gudin charged that Ukrainian children had been solely adopted by Israelis for their body parts. And in 2018, on the eve of Passover, ritual murder rumors inundated the Siberian town of Kemerovo after 41 children were killed in a movie theater fire.

The embers of the Judeo-Bolshevik myth still flicker. A 2017 Russian mini-series about Leon Trotsky portrayed him as the mastermind of the Bolshevik revolution and of the murder of Czar Nicholas II and his family.

Antisemitic myths die hard.