Marcel Reich-Ranicki was an anomaly of the first order, a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor who launched a stellar career as one of the foremost literary critics in Germany.

Reich-Ranicki, who died in Frankfurt on Sept. 18 at the age of 93, was a man for all seasons. He wrote for Germany’s most influential newspapers, Die Welt, Die Zeit and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. He published bestsellers, including his autobiography, Mein Leben. He was the host of a popular talk show broadcast on public television.

In short, he was one of the most influential figures in postwar Germany.

I had the good fortune of meeting him in the spring of 1985, when he was in his prime. Wary of journalists, he initially turned down my request for an interview, only to change his mind after I called him at home.

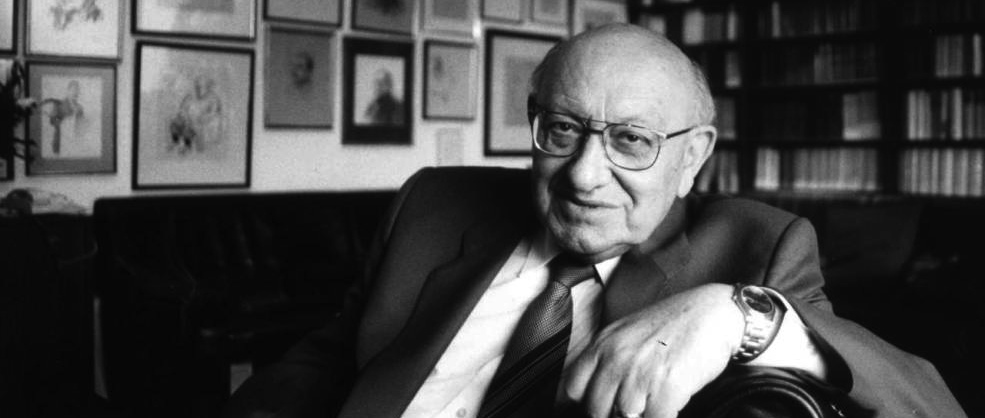

He lived in a tastefully furnished apartment in the West End, an affluent and leafy neighborhood in central Frankfurt. Clad conservatively in black and gray tones, he sat on a comfortable armchair in his living room, whose walls were adorned with framed prints of famous writers and poets. As he talked, he puffed on a cigar. His wife, Teofilia Langnas, who predeceased him, watched him intently from a couch a few feet away.

A courtly man, he was a great talker, answering my questions at length. I spent only about an hour in his company, but my notebook was full to the brim when I left.

Reich-Ranicki was born in Wloclawek, Poland, on June 2, 1920. When his father’s business failed during the Depression, he was sent to Berlin to live with relatives. His parents joined him shortly afterward.

He learned German and delved into German literature in Berlin, the cultural capital of Weimar Germany. With the rise of Nazism, his parents went back to Poland. He remained in Berlin, his imagination fired by the works of Schiller and Goethe, but returned to Poland in 1938 after being deported.

The German occupation of Poland in 1939 changed everything.

Jews were harassed, persecuted and murdered, he noted. As he recalled this period, he grew quiet, looking up at the ceiling. “These were awful years,” he said, “but the most awful years took place a little later.”

Reich-Ranicki and his family were confined to the Warsaw ghetto, where conditions were appalling. Since he spoke fluent German, the Nazis hired him as a translator. He and his parents survived the massive deportations of July 1942, but in September of that year his father and mother were transported to the Treblinka extermination camp, where they perished.

He and his wife, whom he married in 1942, bribed their way out of the ghetto in February 1943, two months before the uprising. For the next two years, they were sheltered in a cellar by a Polish peasant, who would have been executed had the Nazis found the pair.

“He decided we would live,” Reich-Ranicki said. “By day, we were hidden in his cellar. By night, we rolled cigarettes to earn our keep.“

After the war, he joined the Polish Communist party, hoping that communism would eradicate antisemitism. He joined the foreign service and was posted to London as a diplomat.

Reich-Ranicki was soon disillusioned with “the discrepancy between theory and practice“ in communism. In 1950, he was expelled from the party and relieved of his position.

By then, he had discovered that antisemitism was still a formidable force in Polish society.“Antisemitic feelings actually increased,“ he recalled, adding that Poles tended to equate communism with Jews.

Having been rendered jobless, he finally found employment in a publishing house, where he established a German department. At around the same time, he began contributing pieces on German writers to Polish publications.

In 1958, he immigrated to what was then West Germany. When I asked him why he chose Germany, he offered a variety of reasons. He was fed up with communism. Weary of remaining in “an antisemitic country,“ he wanted to live in a democratic nation.

From the outset, he felt at home in West Germany. As he put it, “I changed my address, but not the theme of my work. Just before leaving Poland, I wrote essays about Max Frisch. After my arrival in West Germany, I wrote essays about Max Frisch. I was like a musician who had moved from Moscow to New York. The fundamental repertoire did not, and could not, change.“

Acknowledging he took a risk in settling in Germany, he said, “I wasn`t at all sure I could be a critic in Germany. I was a complete unknown, but I had to try.“

Thanks to help from friends like the novelists Heinrich Boll and Siegfried Lenz, he broke into journalism. “I had a very easy time at the beginning. I had offers at once. I could write for the best newspapers.“

From 1959 until 1973, he wrote for the Hamburg-based weekly Die Zeit. Then he joined the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Reich-Ranicki exerted mass appeal because his writing style was accessible rather than opaque.

In achieving stardom, he was often compared to pre-Nazi Jewish literary critics such as Alfred Kerr and Walter Benjamin. But Reich-Ranicki told me he did not regard himself as a heir to this rich tradition. “That`s finished,`he said curtly.“

Nor was he willing to speculate whether German literary life may have been different had the Nazis not appeared on the scene.

Although he was famous throughout Germany, he regarded himself as an outsider. As he explained, “My father was of Polish-Jewish descent. My mother was of German-Jewish descent. Half of me is a Pole. Half of me is German. The whole of me is a Jew.“

He added, “My education was German. I am a citizen of this country. I am a German literary critic. Heine said that the Jews had made a portable fatherland out of the Bible. I have made a portable fatherland out of German literature. For me, German literature is my Bible.“

When I asked him whether he considered himself a German, he replied, “I have a German passport. I write in German. Culture and literature are my homeland.“