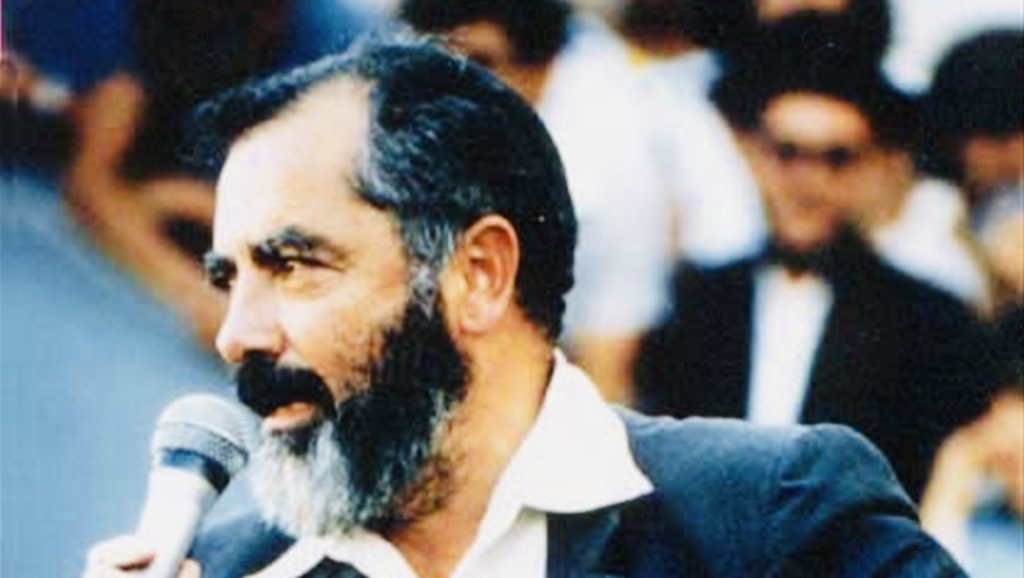

Meir Kahane, the founder of the Jewish Defence League, was an exponent of counter-culture politics and a voice of illiberalism. Assassinated more than three decades ago, he is the subject of Shaul Magid’s erudite and penetrating book, Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical, published by Princeton University Press.

This is not a conventional biography, says Magid, a professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College and a research fellow at the Sholom Hartman Institute of North America. Rather than being a chronological account of his life, which previous books have explored in depth, it is a sober analysis of his beliefs and ideology. “What interests me are the ideas that inform Jewish culture, politics and religion,” writes Magid.

And so this illuminating volume focuses on Kahane’s often incendiary, provocative and reactionary critiques of the American Jewish community and Israel. In dealing with these issues, Kahane dwelled on themes ranging from race and radicalism to Jewish identity and pride.

Although he lambastes Kahane as “a destructive force against human decency,” Magid recognizes that he projected clout and charisma among his followers. In the United States, he was an influential critic of “the hypocrisy of 1960s and 1970s American Jewish liberalism.” And in Israel, where he formed a far-right political party and briefly held a seat in the Knesset, he “tapped into the anger and resentment” of marginalized Israeli Jews excluded from the centers of power.

Unwavering in his outlook, he warned of the dangers of intermarriage and decried the antisemitism of the left during an era when only right-wing antisemitism concentrated minds. A conservative long before the emergence of neo-conservatism, he believed that Jews had an obligation to support Israel, regardless of the correctness or morality of its policies.

Born in 1932 and raised in a middle-class neighborhood of Brooklyn, he was, as Magid observes, a “vexing, disturbing and compelling” product of his times. Kahane was a Modern Orthodox Jew who spent 13 years in the Mir yeshiva, which was transplanted to New York City from Russia and Japan in 1946. Kahane’s father, Charles, was a friend of the legendary leader of the Zionist Revisionist movement, Ze’ev Jabotinsky.

Kahane founded the Jewish Defence League in the spring of 1968 in response to chaos revolving around the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school strike, during which antisemitic pamphlets were distributed by some African American members of the school district. This incident struck a chord with Jews who felt vulnerable, and Kahane took full advantage of their anxieties and fears.

JDL recruits tended to be the Orthodox children of working-class Holocaust survivors. In still other instances, they were the disaffected members of the New Left, who felt abandoned by its sharp criticism of Israel as a colonial settler state.

The JDL prospered during the early 1970s, when Kahane opened new chapters in major cities across the country. But by 1975, the JDL had largely collapsed after the FBI and local police departments charged it with arms smuggling and possession of explosives.

Kahane made aliyah in 1971, having reached the conclusion that Israel was the only possible solution for Jewish survival. Yet he ran afoul of the law in Israel as well. He was arrested over 60 times and was found guilty of numerous offences, including incitement to violence. In 1986, the Knesset branded Kach, his political party, as racist and Kahane was removed from office. After returning to the United States, he served out a prison sentence for parole violations.

An ordained rabbi, Kahane earned a law degree at New York University, but failed to pass the bar exam. He made a living as a congregational rabbi, as a journalist writing for the right-wing Jewish Press, and as the owner of a summer camp where campers learned the martial arts and how to handle guns.

Magid believes he rose to national fame through his involvement with the Soviet Jewry movement, which promoted the idea that Jews in the Soviet Union had the right to emigrate. By the late 1960s, the JDL was, as Magid puts it, the movement’s “militant arm.”

JDL activists turned to violence, vandalizing the offices of a Soviet press agency, tour operator and airline in New York City. The JDL, too, disrupted the performances of touring Soviet cultural troupes such as the Bolshoi Ballet. In January 1972, the JDL bombed the office of Sol Hurok, an American impresario who booked Soviet acts in the United States. The blast killed one of his employees and injured 13, badly tarnishing the JDL’s image, such as it was.

A resident of Israel at the time, Kahane may not have known about the intended bombing. But in Magid’s opinion, he was complicit because he condoned and encouraged the purchase of weapons and explosives. By this point, he goes on to say, the JDL had devolved into “a kind of street gang” and had become an “outlet for Jewish rage.”

Describing Kahane as “one of the most divisive figures of the second half of the twentieth century,” Magid explains that three issues drove his ideological agenda: racism, communism and assimilation.

The issue of race and racism framed his career from start to finish. Kahane insisted the JDL was not racist, claiming he was “against anyone who is against the Jews.” Magid, however, thinks he was personally a racist: “Kahane certainly trafficked in racist language and was adept at the grammar of racism, referring to black neighborhoods in Brooklyn as ‘jungles.'”

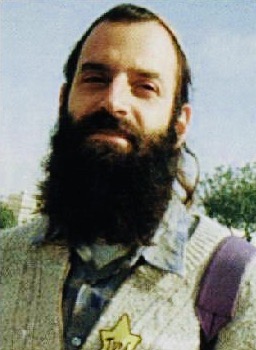

In 1981, while living in Israel, Kahane bought a full page ad in a daily demanding a mandatory prison sentence for any Arab who had sexual relations with a Jewish girl or woman. He also called for the expulsion of Israeli Arabs on a voluntary basis. One of his disciples was Baruch Goldstein, the crazed Jewish settler who killed 29 Palestinian men and boys in a shooting rampage in a mosque in Hebron in 1994.

The Arab citizens of Israel were not his sole target. A religious Zionist who had joined the Bnei Akiva movement in his youth, Kahane was contemptuous of secular Labor Zionists like David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister. As far as he was concerned, Ben-Gurion’s Zionism had produced little more than “Hebrew-speaking goyim,” or “gentilized Hebrews,” and a liberal Hellenistic Jewish state.

His supporters in Israel consisted of three groups — Sephardi Jews from poor neighborhoods and remote development towns who regarded him as an adversary of the Ashkenazi power elite, yeshiva students influenced by the messianic teachings of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, and disgruntled immigrants from the Soviet Union.

A fierce anti-communist, he believed that communism was a major force of antisemitism. To Kahane, antisemitism could only be contained, never eradicated, while communism threatened both religion and nationalism, which he regarded as the twin pillars of Jewish existence.

He outlined his thesis in The Jewish Stake in Vietnam, a book he co-authored with childhood friend Joseph Churba, a Syrian Jew who would become a Republican Party operative. He believed that Jewish support for the U.S. position in Southeast Asia would counteract antisemitism in the United States and help Israel.

“His message to liberal, mostly young American Jews was that they were endangering themselves and Israel by joining the anti-war movement,” says Magid. “Jewish identity in America, Kahane argued, could not survive participation in progressive causes.”

For Kahane, liberalism was the “great challenge” of American Judaism, the factor undermining the legitimacy of Zionism in Israel. “The Jews’ commitment to liberalism, against their own collective interest, was in his view an act of repugnant self-hatred…”

Kahane’s radical critique of liberalism applied not only to the New Left, but to the American Jewish program of assimilation, or Americanization, which, he claimed, had robbed Jews of a positive sense of Jewishness or pride in being Jewish.

In summing up, Magid argues that Kahane drew on the principles of right-wing Zionism and New Left radicalism. “He adeptly used the tactics of the far left for the purposes of the reactionary right,” he says. “His failure was that he was never able to abandon that militancy, even as it was abandoned by other radical groups by the mid-1970s. The JDL became anachronistic in its approach and methods.”

Violence plagued him and his movement, both in Israel and the United States. “He was simply a product of his time yet could not transition out of it,” says Magid. “He failed because he could not overcome his anger and hatred.”

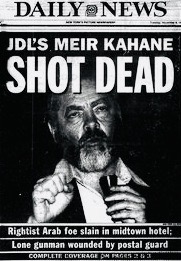

Spurned by the Israeli elite, Kahane was equally a persona non grata in most American Jewish circles on the eve of his untimely death at the age of 58.

Kahane was fatally shot on November 5, 1990 at a hotel in Manhattan. His Egyptian Muslim assassin, El Sayyid Nosair, was acquitted of the murder, but years later he was convicted of charges relating to the first World Trade Center bombing. Magid thinks he had ties to Al Qaeda, and Kahane may have been its first American victim.

Nearly 32 years after his assassination, Kahane’s ideas live on, notably in Modern Orthodox communities in the United States and Israel and among the most extreme settlers in the West Bank.

“He was his own worst enemy, but his influence remains,” concludes Magid on a somber note.