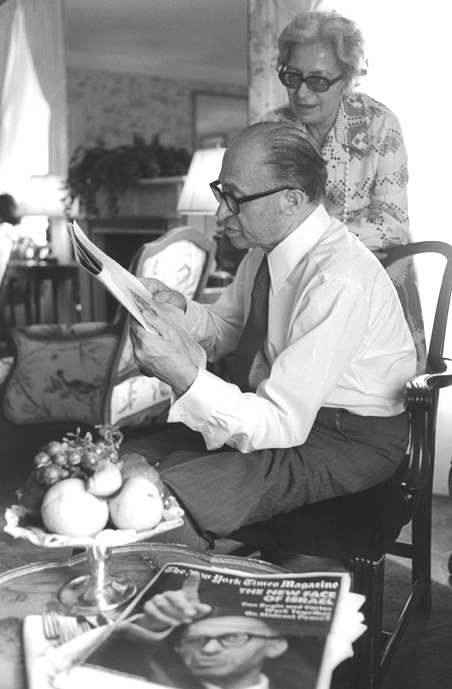

Menachem Begin, the prime minister of Israel from 1977 to 1983, was a man of war and a man of peace, but above all else, he was an ideologue who stuck steadfastly to his beliefs.

A Zionist Revisionist in the mould of his hero, Vladimir Jabotinsky, Begin devoted himself, body and soul, to the attainment of Jewish statehood. Since compromise was not usually a word in his vocabulary, he opposed the United Nations Palestine partition plan and Palestinian statehood. He ceded the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt, thereby enabling Israel to sign its first peace treaty with an Arab state, yet he ordered two invasions of Lebanon, the second one of which proved unpopular and disastrous.

Begin’s mixed legacy is the subject of a biography by Daniel Gordis, Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel’s Soul, published by Nextbook. Gordis, an Israeli who made aliyah from the United States, never met Begin, nor even saw him in person, as he acknowledges in the introduction. Nonetheless, thanks to his skills as a researcher and writer, Gordis paints a sharp and nuanced portrait of Begin.

Calling him the most Jewish of Israel’s prime ministers, given his “finely honed appreciation for the rhythms and priorities of Jewish life and tradition,” Gordis charts his career from Poland to Palestine before launching into an appraisal of his achievements and failures as Israel’s prime minister.

Born in 1913 in Brest-Litovsk, he hailed from a traditional family deeply attached to Zion. Begin joined the right-wing Betar Zionist movement at the age of 13 and never looked back. Due in large part to his oratorical prowess, he rose swiftly in the ranks. After graduating from the University of Warsaw’s law program, he was appointed the head of Betar’s Organization Department. Gordis surmises that he did not immigrate to Palestine prior to World War II because the Jewish Agency gave very few entry certificates to Betar members.

He and his new wife, Aliza, boarded one of the last trains to leave Warsaw before Germany invaded Poland. They hoped to board a ship in Romania bound for Palestine, but in 1940, he was arrested in Vilna, which was occupied by the Red Army. Accused of being an anti-Soviet propagandist, Begin’s imprisonment was one of “profound physical and emotional pain.” Set free a year later, he wandered through the Soviet Union before joining Gen. Wladyslaw Anders’ Free Polish Army, which arrived in Palestine in the spring of 1942.

Reunited there with Aliza, Begin spent close to two years working for Anders, all the while building relations with Betar. After his discharge, he was named commander of Etzel, Betar’s military wing, which was committed to upending the British mandate in Palestine. Etzel was behind the 1946 terrorist bombing of the King David Hotel, which served as Britain’s military and administrative headquarters. Begin never apologized for the blast, which killed 92 people, including 28 Britons.

Claiming that armed force was legitimate in war, Begin ordered the hanging of two British soldiers in revenge for the deaths of two Etzel fighters. Years later, he would say it had been his “most difficult decision.”

Given his hardline views, Begin categorically rejected the 1947 UN plan to divide Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state, calling it “illegal.” On the eve of Israel’s statehood in 1948, Begin’s forces carried out a massacre in the Arab village of Deir Yassin. He expressed “great sorrow,” saying that the villagers had been warned to leave.

Begin was invariably at odds with his Mapai Party adversary, David Ben-Gurion, who would be Israel’s first prime minister. Gordis deals with that issue at some length, paying attention to one incident in particular.

Begin wanted Etzel fighters to be recognized as distinctive soldiers in the new Israeli army, but Ben-Gurion flatly refused, saying there could be only one military force. Begin finally signed an agreement in which Etzel was to be absorbed into the army, but Etzel branches abroad continued to send weapons to their fighters in Israel.

Without informing Begin, Etzel’s leadership in Paris dispatched the Altalena, a ship full of immigrants and arms, to Israel. When the news leaked out, Ben-Gurion was furious, convinced that Begin had broken his promise and was trying to undermine his authority. As the Altalena approached the coast in June 1948, fighting broke out, resulting in the deaths of 19 Etzel and Israeli army soldiers. The incident embittered Begin’s already fraught relationship with Ben-Gurion and tarnished his reputation.

Begin, having fared poorly in Israel’s second general election in 1951, announced he would leave politics and relinquish his post as Herut Party leader. He changed his mind after Ben-Gurion disclosed that West Germany might be amenable to paying Israel reparations for the Holocaust. Begin, whose parents and relatives were murdered by the Nazis, expressed vehement opposition, infuriating Ben-Gurion. Begin set aside his resistance following a vote in the Knesset to approve talks with the Germans.

Four days before the Six Day War, Begin joined Israel’s national unity government, winning a seat in the cabinet for the first time. Within a year and a half, he bolted, angered that the prime minister, Golda Meir, had agreed to consider an American peace plan that would have required Israeli withdrawals from the occupied territories .

Largely through the efforts of retired general Ariel Sharon, Begin established the Likud Party in September 1973, less than a month before Egypt and Syria ignited the Yom Kippur War. Gordis claims, incorrectly, that Egypt’s intention was to destroy Israel rather than to wrest back the Sinai.

Begin’s victory in the 1977 general election propelled him to the prime minister’s office. This gave him the opportunity to more than double the Jewish population of the West Bank by building scores of settlements, some in heavily-populated Palestinian Arab areas. As Gordis observes, Begin’s heart had always been with the national religious camp, which spearheaded settlement growth in the West Bank.

In discussing the arduous negotiations that climaxed with the peace treaty signed by Israel and Egypt in 1979, Gordis takes Begin’s side. He writes that neither Anwar Sadat nor Jimmy Carter, the Egyptian and American leaders, understood Begin’s refusal to even discuss an end to “the settlement project in the West Bank.”

As far as Sadat and Carter were concerned, there was an explicit understanding that, in exchange for a peace treaty with Egypt, Israel would vacate settlements in the West Bank and grant the Palestinians meaningful autonomy on the road to statehood. Begin assumed that Israel’s phased withdrawal from Sinai would relieve him of the obligation to give up what he considered the Land of Israel. In a candid moment, Begin told Carter’s national security advisor, “My right eye will fall out, my right hand will fall off before I ever agree to the dismantling of a single Jewish settlement.”

Gordis’ account of Begin’s momentous decision to bomb Iraq’s nuclear reactor in 1981 is concise and clear. Begin realized that it would be a risky, even dangerous, operation. But he was convinced that Israel’s future was at stake.

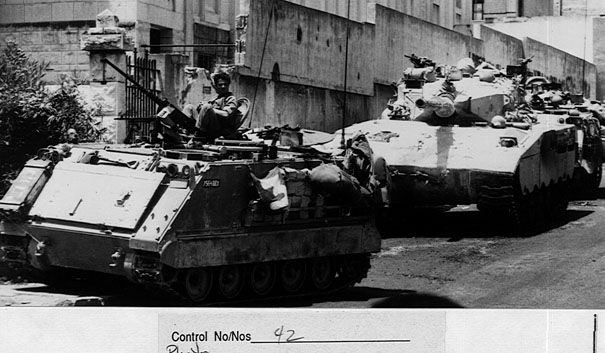

Begin’s gamble to invade Lebanon in 1982 was predicated on the false assumption that Israel could alter the geopolitical landscape in that country to Israel’s advantage. According to Gordis, Sharon, the defence minister, “manipulated and outfoxed” Begin. Begin had pledged not to advance more than 40 kilometres into Lebanon. Sharon made a mockery of Begin’s promise by pushing further north and occupying Beirut, the Lebanese capital.

The morass into which Israel had stumbled dejected Begin and affected his health, which in recent years had been frail. “But the greatest blow was yet to come,” says Gordis. Aliza, his beloved wife, died while he was away on business in Los Angeles. He never recovered from her death.

Gordis suggests that Begin resigned due to his unwillingness to greet West Germany’s chancellor, Helmut Kohl, on a state visit. “For Begin, whose parents and brother had been killed by the Germans, and who had railed against German reparations because he believed that the Germans should forever bear their guilt, the fluttering of German flags (in Jerusalem) was simply too much for a man whose reservoirs of strength were depleted.”

From 1984 onward, Begin was a recluse, rarely leaving his home. He spent his days in pajamas and a robe reading newspapers. He died on March 9, 1992.

Gordis concedes that Begin defies understanding in many circles. As he puts it, “Begin’s association with force is a critical dimension of the complexity of who he was. That one man could be so emblematically associated with both peace-making and war-making is difficult for many to fathom today.”

This, in essence,was the quintessential Begin.