Francine Pelletier’s 52-minute biopic, Mordecai Richler: The Last Of The Wild Jews, skims over rather than examines the late Canadian writer’s career. Nonetheless, her documentary, now being screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation, is thought-provoking and never less than interesting.

Released nine years after his untimely death in 2001 at the age of 70, it’s an impressionistic portrait of a great and cantankerous literary figure.

A novelist, journalist and screenwriter, he belonged to an exclusive club of North American Jewish men of letters who achieved critical and commercial success from the 195os onward. Their members included Philip Roth and Bernard Malamud.

Pelletier, a French Canadian journalist from Montreal, does not provide viewers with a standard chronological account of Richler’s life. She jumps around a lot, ignores his earliest novels and forays into cinema, and relies on interviews with his wife and contemporaries to fill in blanks.

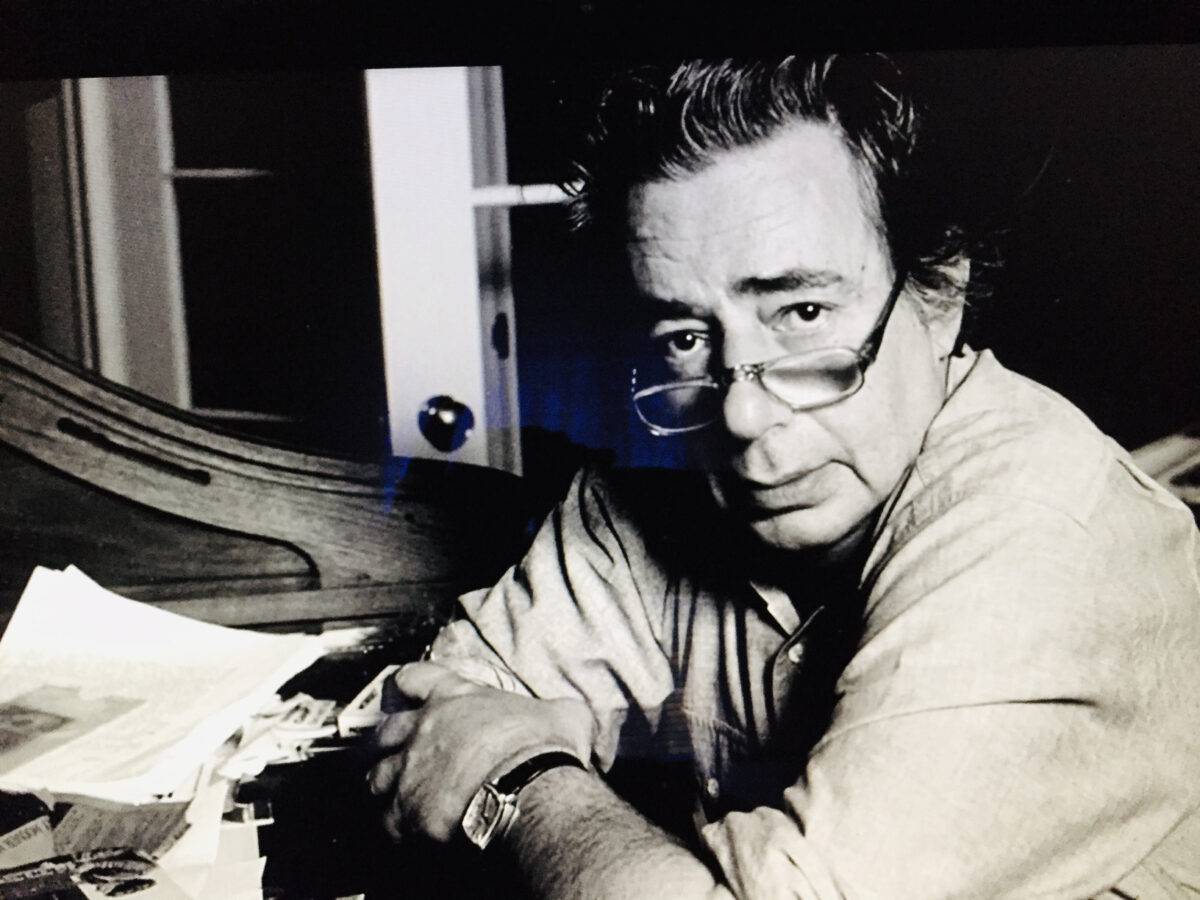

In the very first scene, the camera pans on his study and bookshelves, filled with his published novels. Florence, his elegant widow, appears and offers comments about her late husband. In her view, he possessed a profound ability to judge people very well. She describes this trait as his “shit detector.”

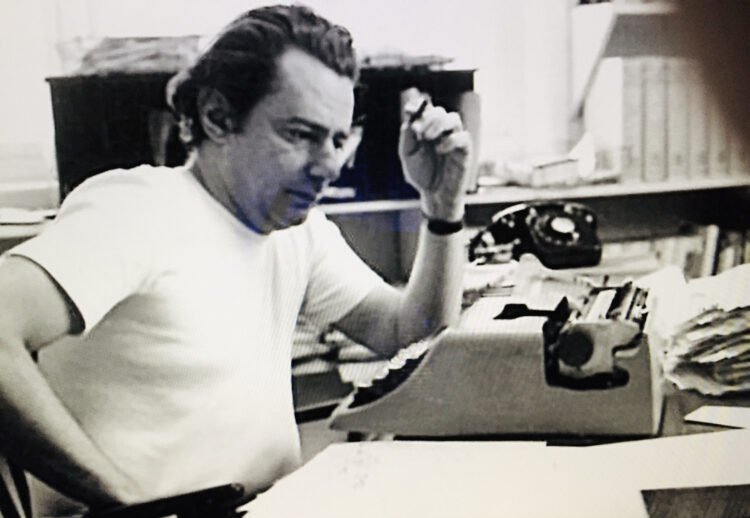

Although he could fill a room with his “big personality,” he was shy and reserved, as I discovered when I interviewed him in the 1990s after the appearance of his latest novels. A laconic man given to “silences,” he met his wife-to-be, a model, in London and fell madly in love with her when they were still both married. Richler’s old friend, the filmmaker Ted Kotcheff, says he would not allow “stupid reservations” to get in his way.

That he was “unpolished’ was of no concern to Florence because she liked his “rawness.” From the very beginning, she understood that his dedication to his craft came before anything else. Calling him as a “very, very difficult person” to be around, Florence says he was not a talker. Yet his cutting wit and repartee could be withering.

Pelletier glosses over his immigrant parents and mentions his grandfather, Rabbi Yudel Rosenberg, only in passing. Richler rebelled against the strictures of his observant upbringing in Montreal and remained secular until the very end. In an archival clip, a young Jewish woman asks him why he married a “shiksa.” Drawing on a cigarillo, he calmly replies, “Because I loved her.”

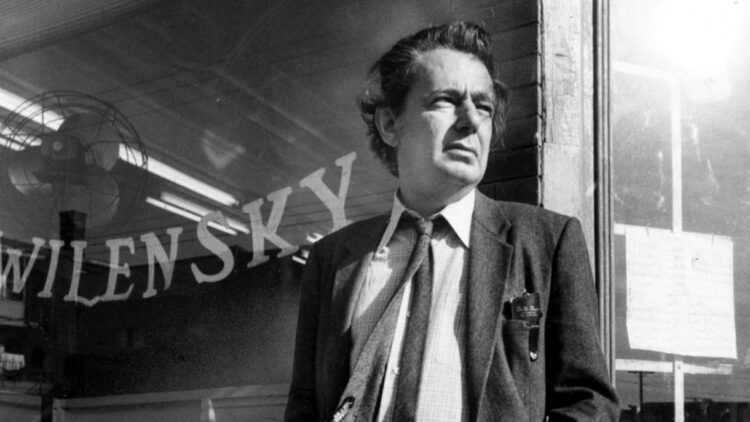

Although he was a non-conformist, Richler was a quintessential Montreal Jew, caught between the French Canadian and Anglo communities and acutely aware of the antisemitism emanating from both of these two solitudes.

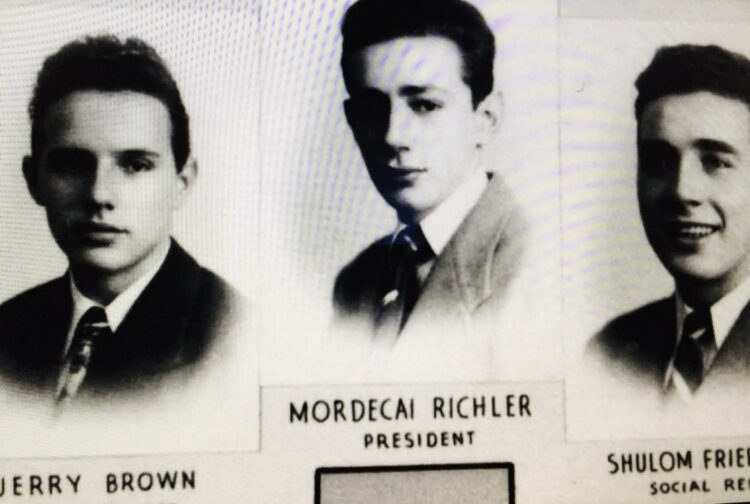

At Baron Byng High School, whose student body was more than 90 percent Jewish, Richler gravitated toward writing. While many of his classmates had no idea what they would do after graduation, Richler was certain he would become a professional writer.

When he was 19, he left Montreal, seeking adventure and “the holy grail of literature” in Europe. He was influenced, by among others, the Russian novelist Issac Babel, a “wild” Jew who was the polar opposite of the timid shtetl Jew who could be pushed around by gentiles. Like Babel, Duddy Kravitz — one of Richler’s most enduring characters — was a liberated man who couldn’t care less what others thought of him.

In his novels, he portrayed the Jews of Montreal in less than a flattering manner, which is why he generally aroused their anger and disdain. As his fame grew, he became something of an icon, but he could still unsettle them. At a school reunion in 1980, a gratuitous comment he made in a curt speech elicited a chorus of boos.

According to the novelist Margaret Atwood, Richler was suspicious of “ideological straitjackets.” Nor did not take kindly to tribalism. In what Pelletier disparagingly calls his “last crusade,” he took aim at Quebec’s language laws and claimed that Qubecois nationalism, at least to some extent, was insular and rooted in antisemitism.

His friend, the newspaper cartoonist Terry Mosher, believes he went “overboard” in his scathing appraisal of French Canadian nationalism.

Diagnosed with terminal cancer at the height of his powers, Richler hoped for a reprieve of five to seven more years. This was not to be, says Florence, tears welling up in her eyes. Yet Richler had a good run and is remembered today as one of the outstanding Canadian novelists of the last century.