When I encountered my first Yiddish text in the archives of Canadian Jewish Congress, sometime in the early 1980s, I had never heard the language spoken. There it was, written in Hebrew characters, undecipherable. I am not quite certain, but my first brush with the idiom must have been in the form of old yellowed clippings from the Keneder Adler, Montreal’s Yiddish daily, going back to period shortly before or after the war.

At the time, I had begun taking Hebrew lessons with a chazan in the Montreal Reconstructionist synagogue, but Yiddish is very different from the language of the Bible. In Yiddish, words can have up to 20 letters and most of the roots are Germanic. Not only this, but the Yiddish texts I was stumbling upon in the archives were entirely secular in nature. They consisted of political discussions, descriptions of events and information newsworthy at the time.

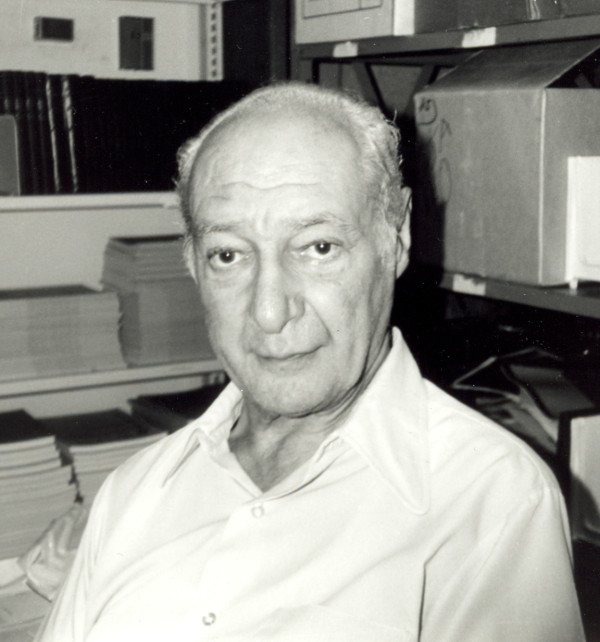

David Rome, who was the archivist at the time, probably saw me hesitate in the face of such a phenomenon: an historical document written in Yiddish. I was in the Congress archives to deepen my sense of the 1930s, at the time when the institution reemerged, and I was trying to determine what kind of relations Francophones and Jews had developed in Montreal during this troubled period.

Rome was a very patient man. Most archivists are. He had been seriously involved during the 1950s and 1960s in a dialogue with French Canadian intellectuals through the Cercle juif de langue française. Today this is something historians study, but then it was a bold experiment to launch the beginnings of a new and more positive relationship between the two groups.

So Rome was aware that it was unusual for the Congress archives to welcome many decades later a young Francophone researcher interested in writing about this topic. He took me under his wing and decided to gradually introduce me to the record found in Congress archives concerning this complex issue.

This meant studying Jewish immigration to Montreal in the 20th century, antisemitism among French-Canadians, the history of Congress itself and the response elicited by Jews. Bit by bit, he helped me grasp that there were two types of documents in the archives: memos, letters and pamphlets written officially in English, and those that had been prepared in Yiddish and which contained a more “internal” view of the subject.

In other words, what circulated broadly beyond the community and what was meant as a discussion among Jews only. Likewise, articles and editorials in the Keneder Adler, today shrivelled up and found in old files, offered an account of the strategies devised within the inner circles of the community.

Rome also introduced me to the Yiddish literature that had been produced in Montreal in the inter-war years and during the post- Holocaust period. This came as a total surprise to me. Who knew among the Francophones that poetry had been published in Canada in a third language besides English and French?

Not only had poets expressed a creative impulse in Yiddish, but pedagogues had also published in this idiom, plus novelists, playwrights and chroniclers of Montreal Jewish history. And there they were, in the Congress archives, row after row of books, encyclopaedias, literary journal and historical studies, entirely Canadian and entirely in Yiddish, most long forgotten and collecting dust in dark corners.

A similar reaction took place when I went to the Montreal Jewish Public Library. Somehow sensing my interest and curiosity, one of the more senior employees of the institution, Golda Cukier, took me without my asking to a back room to show me Montreal Yiddish publications.

I especially remember one of the large anniversary issues of the Keneder Adler, probably dating back to the 1930s, emblazoned with large bold Hebrew letters in blue and gold. I soon realized that learning the language would become a professional obligation if I was to go beyond the accepted notions then prevalent with regards to Francophone- Jewish relations in the 20th century.

Here was a treasure trove of documentation that had not been touched for decades and that few researchers had the linguistic skills to read. Little did I know that this would lead me to a very rich journey through the cultural experiences lived by the immigrant generation, at a time when Yiddish was clearly the dominant language in the Montreal community.

Historians and particularly anthropologists learn languages to gain better insight into the internal logic of societies and cultures that they are studying. Particularly in the case of situations involving inter-cultural exchange and dialogue, it is not enough to consult translations or trust external sources.

One has to delve into the material from the point of view of the “other” participant, from within his own perceptions and emotions. This Yiddish would provide me in abundance. But first I had to learn the language. In itself it was not such a difficult task, as Yiddish is an Indo-European idiom which has many of the linguistic features found, for instance, in Latin, which I had studied in my youth.

Once I had mastered the phonetic values of the Hebrew alphabet as applied to Yiddish and developed the required reading skills, much would have been accomplished. I felt that the adventure was worth embarking upon, all the more since I knew German well and had already absorbed the basic Hebrew words found in Yiddish.

There lay within reach a vast body of documents of particular significance to the subject that I was trying to comprehend. The most difficult problem at hand, for me, was that no Francophone researcher had ever attempted to bridge the gap between a Jewish language and French Canadian history. Entering unchartered territory remained my greatest challenge and my deepest motivation.

It took me five years to learn the language at the Department of Jewish studies of McGill University. This was in the mid-1980s. Progressively, with much help from my professor, Leib Tencer, who was a native speaker, I gained enough fluency to begin reading documents by myself at the Congress archives. This was a huge step forward. At first, I fumbled through with the help of a dictionary, but soon I could make sense of simple statements.

By the late 1980s, I boldly took to translating the poetry of Jacob-Isaac Segal, and in 1992 I published a bilingual anthology of his works, Yiddish to French, at les Éditions du Noroît. This had never been done before. More translations followed, and this is essentially how I perfected my knowledge of the language.

Over the years I decided to produce French language versions of the memoirs of Israel Medresh, Simon Belkin, Hirsch Wolofsky, Sholem Shtern and Hershl Novak, all early twentieth century immigrants to Canada. These translations appeared in Québec City at les Éditions du Septentrion.

Finally, in 2012, I published a book-size literary biography of the poet that had so deeply impressed me when I first approached Yiddish, Jacob Isaac Segal.

Today, after all these literary adventures, Yiddish has become an intimate part of my intellectual life. When I approach a written text in that language, I do not feel any distance. It is as if I had absorbed most of the cultural reflexes involved in understanding the idiom.

Yes, it was much work, but my reward has been to gain a first-hand access to the language of the first East European generation that settled in Canada roughly 100 years ago.

That in itself is priceless.

Pierre Anctil is a professor of history at the University of Ottawa.