Nazis in Germany and neo-Nazis throughout the world have exploited music and song as instruments of unity, camaraderie and aggression, panelists at an online seminar said recently.

During the forum, sponsored by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City, two academics, a former white supremacist and a journalist from Italy spoke of the intersection between music and bigotry.

In his lecture, Edward Westermann — a professor of history at Texas A & M University and a specialist in the Holocaust — said the Nazi movement in Third Reich deployed music and song to amplify a host of interlocking themes ranging from the notion of German dominance over Europe to the promotion of sacrifice for the fatherland and aggressive masculinity.

At the Sobibor extermination camp in Poland, music was played to both lull and humiliate newly arrived Jewish prisoners, he noted. He added that songs engendered bonding among guards and reinforced their existing values.

Westermann cited the case of a Nazi official in occupied Ukraine, Wilhelm Westerheide, who took part in a two-week massacre of some 15,000 Jews. As they were shot in cold blood, he and his accomplices, as well as a few German women, relaxed at picnic tables, gorging themselves with food and alcohol and listening to the soothing strains of classical music.

Near the Ukrainian village of Cutnow, a German execution squad killed 300 to 400 Jews. As they were led away to their deaths, a band cranked out music, noted Westermann.

Kirsten Dyck, the author of Reichrock, a book on the white power music industry, discussed the neo-Nazi music scene from the perspective of the past and the present.

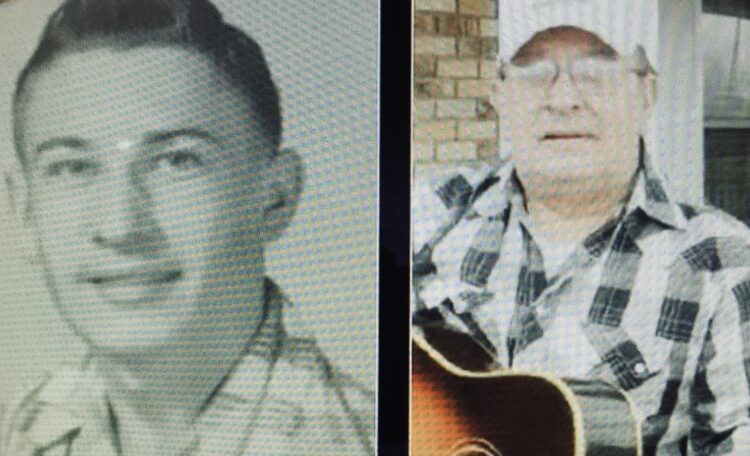

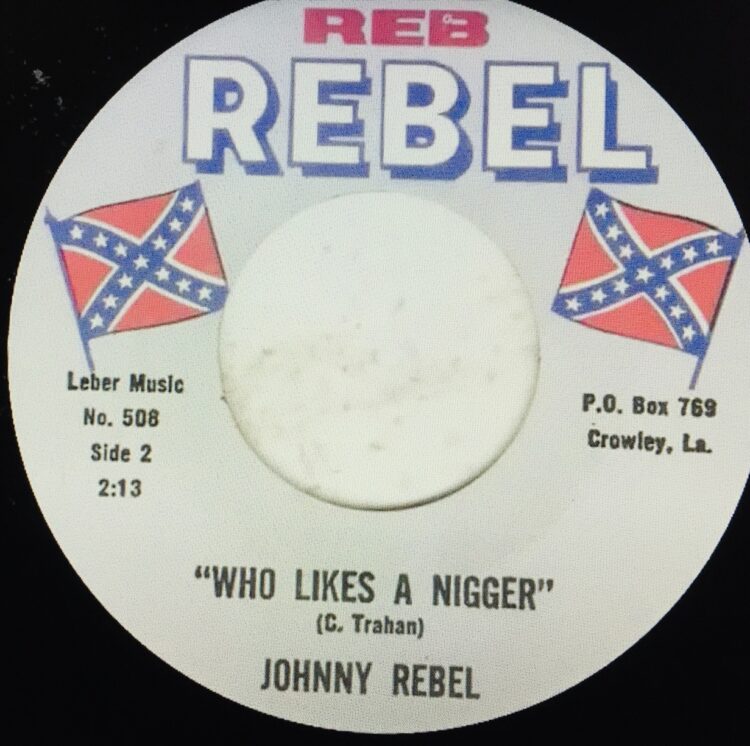

During the 1960s, an accomplished American musician named Clifford Trahan, known colloquially as Johnny Rebel, sold so-called “hate country” music at Ku Klux Klan conventions and country fairs in the south.

The man who started the white power music industry in the 1980s was a punk rocker named Ian Stuart Donaldson, who headed the Skrewdriver band. With the passage of time, he began to associate himself with radical right-wing groups, she said.

In West Germany, bands such as Bohse Onkelz and Die Deutschen Kommen released racist records, while Rock-O-Rama Records morphed into an important distributor of such material.

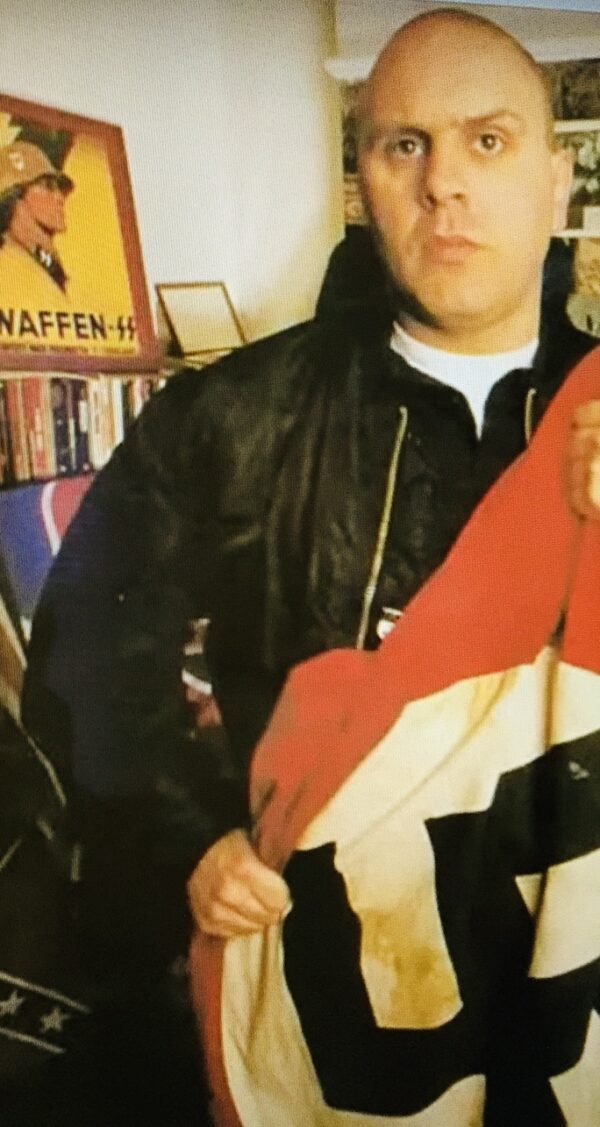

Under the label of Resistance Records, the Canadian rocker George Burdi and his band churned out a stream of racist records. When Burdi moved to Detroit from Toronto, his record company became the preeminent white power label in the United States.

Burdi later renounced racism, but his label continued producing racist recordings.

During the late 1980s, the band Angry Aryans specialized in the production of what Dyck described as “hate core” music. She also mentioned nationalist socialist “black metal,” “hate folk” and “Nazi hip hop” music.

Shannon Foley Martinez, a former neo-Nazi who turned against the movement and has since delivered anti-racist speeches, recalled that music was a central element and a cohesive force in the lives of American neo-Nazis and white supremacists.

She was 15 years old when she was radicalized. “It happened through music,” she said in a reference to the sing-along “Oy” genre of music.

Racist leaders such as William Pierce and Richard Butler recognized its value in building comradeship and community, she said.

Luca Signorelli, an Italian journalist who covered heavy metal and black metal bands, called their screechy genre “a music of rejection,” with no concession to melody. The musicians in these bands were basically nonconformists steeped in racism, he said.