Maybe, just maybe Benjamin Netanyahu got carried away by the inconclusive results of Israel’s March 2 general election, the third in less than a year.

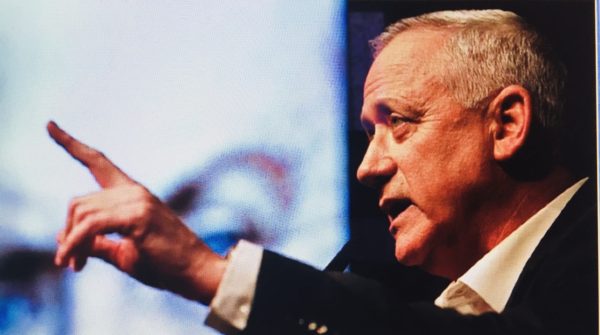

Aiming for a record fifth term in office, the 70-year-prime minister sounded euphoric as he addressed jubilant supporters following the election. Calling the projected outcome “the biggest victory of my life,” Netanyahu exclaimed, “We won against all odds. They eulogized us, but we prevailed. We made lemons into lemonade.”

Not exactly.

With all the ballots counted by March 5, Netanyahu’s right-wing Likud Party marginally improved its performance by winning 36 out of 120 Knesset seats, or 235,000 more votes than in the last election, representing 29.4 percent of the electorate.

Benny Gantz’s centrist Blue and White Party proved to be something of a disappointment, picking up only 33 seats, several less than in the April and September elections, representing 26.5 percent of all voters.

The leftist Arab Joint List won 15 seats and the left-of-center Labor-Gesher-Meretz alliance won 7. Secular right-wing and ultra-Orthodox parties won a total of 29 — Shas 9, United Torah Judaism 7, Yisrael Beytenu 7 and Yamina 6.

Netanyahu’s parliamentary bloc of rightist parties amassed a combined total of 58 seats, falling three short of an outright majority. By comparison, the centrist/left-wing bloc, consisting of Blue and White, the Arab Joint List and the Labor-Gesher-Meretz faction, accumulated 55 seats, six shy of a majority.

The outcome is a case of deja vu all over again.

Neither bloc won a sufficient number of seats to form a majority coalition government. This is precisely what happened in the previous two elections, leaving Israel in a state of political paralysis and uncertainty and Israeli voters very frustrated.

So why was Netanyahu so upbeat in the wake of the election? He probably believes he can peel off at least three seats from the opposition and thereby cobble together a government and prolong his record as Israel’s longest-serving prime minister.

This sanguine calculation may be wishful thinking.

He could turn to Avigdor Liberman, the leader of the Yisrael Beytenu Party, to break the current deadlock, but in the last two elections Liberman did not play ball. With his seven seats, Liberman is a kingmaker yet again and could make all the difference by catapulting Netanyahu into majority territory. But this scenario looks murky. Liberman has vowed not to join a Likud-led government that includes ultra-Orthodox parties. By the same token, he has refused to join a coalition that includes the Arab Joint List. “We won’t move a millimeter from what we promised our voters,” he declared.

On the other hand, Liberman has said that a fourth election should not be held. What he precisely has in mind is still unclear.

Another issue is in play, too.

Netanyahu, having been indicted by the attorney-general on criminal charges of fraud, breach of trust and bribery, goes to trial on March 17 and thus may not be in a legal position to assume the prime ministership. In 2008, lest it be forgotten, he said that Ehud Olmert, the sitting prime minister who faced criminal charges, should be disqualified from running in the next election.

It’s still uncertain whether President Reuven Rivlin can legally ask Netanyahu to form a government after the final results of the election are presented to him. Two months ago, the Supreme Court declined to issue a ruling on the subject, but this time it may have no alternative but to take a firm position on this issue, which is unprecedented in Israel politics.

Netanyahu’s path to the premiership also could be blocked by the Knesset. On March 5, Liberman said he would support a bill to deny him the opportunity to continue serving as prime minister. Parliamentarians from Blue and White, Labor-Gesher-Meretz and the Arab Joint List have said they would support such legislation, which could pass with a slight majority.

In response, Netanyahu accused Gantz of seeking to defy the will of the public and undermine democracy. “Gantz lost and now he’s trying to steal the election,” he claimed.

Netanyahu finds himself in what could be a desperate situation.

He is fighting not only for political survival but for his personal freedom. If convicted in court of corruption, he could face jail time like Olmert, who served 16 months in prison. This would be quite a fall from grace for a politician as confident and self-entitled as Netanyahu.

If reelected, however, he could try to decriminalize the acts of which he is accused.

Given the high stakes in this election, Netanyahu engaged in a mudslinging campaign to try to derail Gantz’s candidacy.

Netanyahu archly questioned his competence and fitness for office, circulated rumors that his cell phone had been hacked by Iran, and insinuated he had driven a high-tech company he had managed into the ground. As well, Netanyahu released a recording in which Gantz’s advisor, Israel Bachar, was heard saying he lacked the courage to attack Iran. Meanwhile, Netanyahu’s son, Yair, tweeted that Gantz had sent salacious sex videos and recordings to a much younger woman with whom he allegedly had an affair.

No shrinking violent, Gantz accused Netanyahu of lying and incitement. “Your obsession with evading prosecution has driven you to lie, to tear us apart, to sow division, to spread malicious rumors. Netanyahu, you are poisoning Israel. Every opponent who runs against you faces this campaign of mud.”

Gantz, a former chief of staff of the Israeli armed forces whom Netanyahu appointed, landed a hard blow by releasing a tape in which six former directors of the Mossad and Shin Bet security services charged that Netanyahu had lost the moral and ethical right to govern Israel.

As Tamir Pardo, the Mossad’s former director, said, “A prime minister who is not a personal example for all Israeli citizens is a clear and concrete danger to the safety of the State of Israel.”

During the campaign, Netanyahu tried to make hay of the U.S. peace plan released by President Donald Trump on January 28. The pro-Israel American “vision” of peace, rejected by the Palestinians and Arab states, does not even meet Palestinian minimal demands, but to Netanyahu it represents a golden chance to annex all the settlements and outposts in the West Bank, plus the Jordan Valley.

Netanyahu, too, appealed to his base by advancing three massive settlement projects in East Jerusalem and the West Bank that would destroy the possibility of a viable two-state solution. The announcements called for the construction of thousands of housing units on the site of Qalandia airport, Givat Hamatos and an area known as E1.

These projects would sever the contiguity between East Jerusalem, Ramallah and Bethlehem and block the sole land corridor connecting the northern and southern parts of the West Bank.

Netanyahu’s appeal to his nationalist base worked to some extent. On the eve of the election, Likud polls indicated that Netanyahu had caught up with Gantz in terms of the number of seats he could win and that he was closing in on forming a majority government.

“We are very close to victory,” he boasted at a rally a few days before Israelis cast their ballots.

But as of now, Netanyahu is far from assured of a majority. A fourth round may be necessary, unless Liberman throws his support behind Gantz.