Shimon Peres, Israel’s three-time prime minister and ninth president, was a dreamer who fused idealism with practicality. A hawk who was instrumental in building the Israeli armed forces in the late 1940s and 1950s, he was also a dove who strove for peace with the Palestinians and Israel’s Arab neighbors in the 1990s.

Peres, who was born in 1923 and died in 2016, is the subject of Richard Trank’s two-hour biopic, Never Stop Dreaming: The Life And Legacy of Shimon Peres, a brisk documentary that accentuates the positive. Currently being streamed on the Netflix network, it chronicles his journey from an old land, Poland, to a new one, Israel.

Originally released in 2018, it pays homage to a politician who remained young at heart, innovative and true to his ideals. Composed of archival footage, interviews with foreign politicians such as Tony Blair, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, and lengthy recollections from Peres himself, it paints a picture of a dedicated, driven person who devoted body and soul to the Zionist movement and the state of Israel.

It unfolds in chronological order, beginning in the Polish shtetl of Vishneva, which is now in Belarus. Raised in a traditional Jewish home imbued with a love of Zionism, he was the son of Yitzhak and Sara Persky. By Trank’s account, he was largely influenced by his mother and grandfather, Zvi, who perished in the Holocaust.

Yitzhak, a lumber merchant, settled in Palestine in the early 1930s, soon to be followed by his family. They embarked in Jaffa, which Peres compares to a “different planet.” Intoxicated by the bright sunshine and the fragrance of orange blossoms, he felt alive and reborn.

Already a fluent Hebrew speaker, Peres spoke the ancient language in a heavy Ashkenazic accent, which he tried but failed to jettison. A kibbutznik, an aspiring farmer and an effective public speaker and political organizer, he became a rising star in the socialist Mapai Party, the forerunner of the Labor Party, which ruled Israel from 1948 to 1977 and periodically from that point onward.

David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, was impressed by Peres’ skills and savvy and and asked him to scour the world for weapons at a moment when Israel was short of military equipment and munitions due to a British and American arms embargo. Successfully completing this task, Peres always remained a civilian, never serving in the armed forces

As deputy minister of defence, Peres formed Israel’s special bond with France, which became its chief arms supplier and ally in the 1956 Sinai War.

Peres, in the face of heavy resistance from major Israeli politicians, established Israel as a nuclear power thanks to secret shipments of French uranium. He also negotiated an arms deal with West Germany.

On the eve of the Six Day War, he and others convinced Prime Minister Levi Eshkol to appoint Moshe Dayan as minister of defence. Golda Meir, Eshkol’s successor, disliked Peres, but appointed him to her cabinet.

After her resignation in 1974, Peres and Yitzhak Rabin contested the leadership of the Labor Party. Rabin won by a narrow margin, succeeding Meir as prime minister. Rabin reluctantly named his rival as defence minister.

Trank plays down Peres’ activism in expanding Israeli settlements in the West Bank, but dwells on his role in convincing Rabin to mount the daring Entebbe commando raid in Uganda in 1976.

With Rabin’s resignation in 1977, Peres replaced him as prime minister. Much to Peres’ humiliation, he was defeated by Menachem Begin of the Likud Party in that year’s general election.

From 1984 onward, Peres and Yitzhak Shamir shared the premiership on a rotating basis in a national unity government. As foreign minister under Shamir, Peres negotiated a joint power-sharing agreement in the West Bank with King Hussein of Jordan. Much to Peres’ bitterness, Shamir vetoed it.

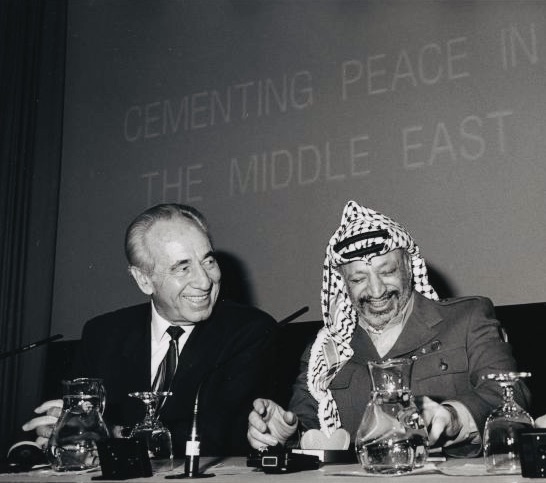

Rabin, having resumed his job as prime minister in 1992, appointed Peres as foreign minister. Realizing that Israel had no alternative but to deal with the PLO, headed by Yasser Arafat, Peres initiated secret negotiations with its representatives in Norway, resulting in the 1993 Oslo principle of declarations.

Riding on its momentum, Peres engaged Jordan in talks, which led to Israel’s 1994 peace treaty with the Hashemite kingdom.

With Rabin’s assassination in 1995, Peres once again became prime minister. By then, their contentious relationship had apparently improved.

A wave of Palestinian terrorist attacks, causing the deaths of more than 60 Israelis, doomed Peres’ chances of winning the 1996 election. “I knew in my heart I had lost the election,” says Peres glumly. Benjamin Netanyahu, an ardent Oslo foe, defeated Peres by a razor-thin margin.

Much to the shock of his colleagues in the Labor Party, Peres jumped ship and joined Ariel Sharon’s new centrist Kadima Party. In the wake of Sharon’s stroke in 2005, he was named deputy prime minister in Ehud Olmert’s cabinet.

With the resignation of Israel’s president following a sex scandal, Peres stepped into his shoes. Sonya, Peres’ wife, wanted him to retire, but he refused, tragically tearing asunder their marriage.

Peres stepped down in 2014, devoting himself to his pet project, the Peres Center for Peace and Innovation in Jaffa. As Peres’ friend Bill Clinton comments, he was an optimist who believed that tomorrow could be better.

“My real talent was to dream,” says Peres.

And in this capacity, as Trank’s informative film amply demonstrates, he contributed mightily to Israel’s development as a military power and a thriving democracy.