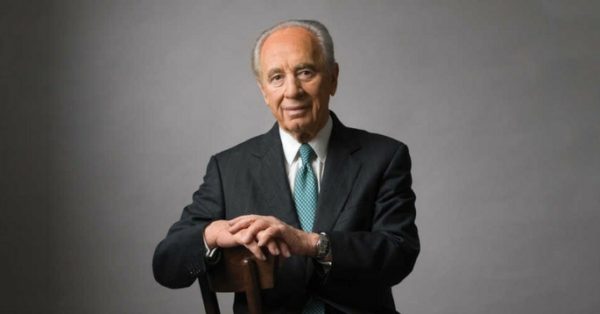

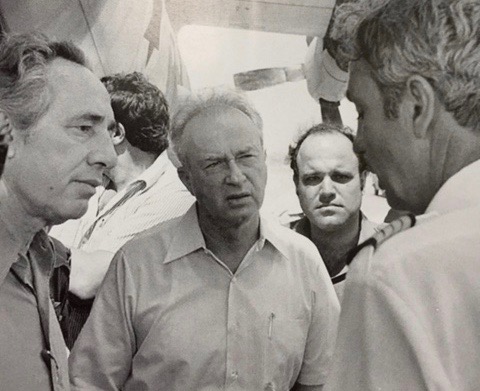

Shimon Peres, a member of Israel’s founding generation, was one of its most distinguished sons. A wunderkind who was deputy director of the ministry of defence at the age of only 29, he held a succession of ministerial posts from the 1950s onward, the most important of which were the defence, foreign affairs and finance portfolios. Twice prime minister, he was president from 2007 to 2014. He died on September 28, 2016. He was 93.

Following his death, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu aptly observed that it was “the first day of the State of Israel without Shimon Peres.”

So true.

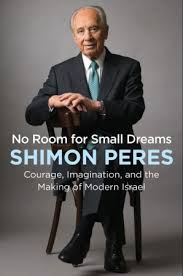

Several weeks before his passing, he submitted the manuscript of his autobiography to his publisher. Highly readable and sweeping in content, No Room for Small Dreams: Courage, Imagination and the Making of Modern Israel (Custom House/Harper Collins) takes a reader on a fascinating journey from Poland, his birthplace, to Israel, the land of his longing.

He was born in Vishneva in 1923, a remote shtetl without running water or electricity. “We lived a simple life,” he says.

Neither of his parents considered Vishneva their permanent home. Their eyes were fixed on the Jewish ancestral home in Palestine, a British mandate. “Herzl’s dream had become my own,” he writes in a reference to Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism. “We spoke Hebrew, we thought in Hebrew …”

Peres’ father, Yitzhak, a merchant, set off for Palestine in 1932, his business having been crushed by “antisemitic taxes.” In 1934, he and his younger brother and their mother, Sara, joined Yitzhak in Palestine. His grandfather remained behind. He would be murdered by the Nazis a few years later.

Peres’ recollection of his arrival in the port of Jaffa is cast in hyperbole: “As I scanned the boats looking for my father, I noticed scores of local Jews whom I barely resembled. In perpetually grey Vishneva, every Jew I knew was incredibly pale. To be among these men who were tanned by the sun and chiselled by the hard work of cultivating the land was to be among heroes. I wanted nothing more than to join them, to become one of them.”

He spent his formative years in Ben-Shemen Youth Village, which he recalls as “the most wonder place place I have ever known.” There he he learned agricultural and martial skills.

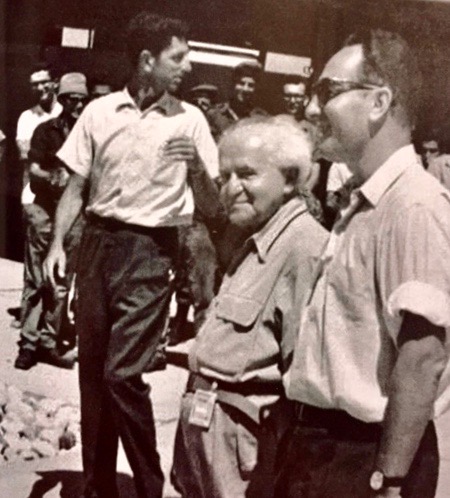

By chance one day, the legendary David Ben-Gurion, one of the leaders of Palestine’s Jewish community, sat next to him in the back seat of a car. “His vision for our future state — safe, secure, democratic and socialist — was an inspiration to me … Suddenly, I was going to get two hours with him, with nothing to interrupt us …” Peres’ nearly breathless account of their encounter is quite revealing.

He spent some of the happiest days on Kibbutz Alumot, where conditions were spartan but where he solidified his relationship with his wife-to-be, Sonia. Soon enough, Peres was working for Ben-Gurion’s labor Zionist movement.

In 1947, on the eve of Israel’s declaration of independence and the first Arab-Israeli war, he was summoned to Ben-Gurion’s office in Tel Aviv. Worried that the proclamation 0f Jewish statehood would lead to an Arab invasion, Ben-Gurion handed Peres an extensive shopping list of weapons he should acquire abroad. “Days earlier, I had been milking cows on a kibbutz. Now I was being thrown into one of the most dramatic periods of my life.”

Peres purchased the weaponry in Czechoslovakia, whose factories had ironically supplied Nazi Germany, and in the United States, which had imposed an arms embargo against all Middle Eastern states.

During these momentous months, he formed a special bond with Ben-Gurion, who “seemed to like how hard I could work, and how little sleep I tended to need or desire.” Asked why he trusted Peres, Ben-Gurion replied, “Three reasons. He doesn’t lie. He doesn’t say bad things about other people. And when he knocks on my door, he usually has a new idea.”

Appointed director general of the ministry of defence in 1953, Peres finally convinced Ben-Gurion, but not the foreign ministry, that a partnership with France would serve Israel’s strategic interests. In short order, he talked France’s deputy prime minister, Paul Reynaud, into sell weapons to Israel. “It was our first arms deal with a major world power,” he writes.

As a result, Israel acquired several types of fighter jets, all of which would be crucial in Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six Day War.

After Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal and ordered British troops out of the country, Peres played a pivotal role in aligning Israel with France and Britain in the attack against Egypt. He describes the process at some length.

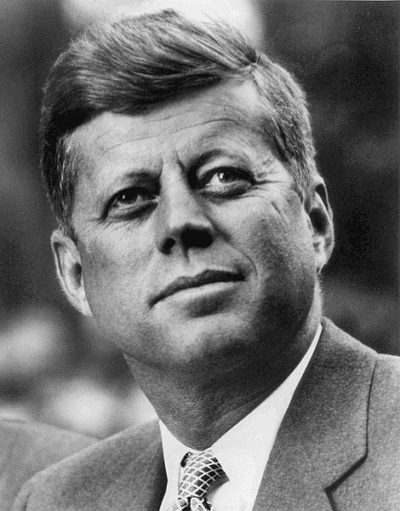

Peres was also instrumental in persuading France to construct a nuclear reactor in Dimona. When U.S. President John F. Kennedy asked Peres whether Israel was building a stockpile of nuclear bombs, he replied, “I can tell you most clearly that we shall not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons to the region.” Peres’ impromptu statement of “nuclear ambiguity” would become Israel’s long-term policy.

“The existence of Dimona may have increased our enemies’ desire to destroy us. But the suspicions it generated stole from them the belief that they could overpower us.” He adds, “Believing that Israel had the power to destroy them, they one by one abandoned their ambitions to destroy us.”

As minister of defence during the 1976 Entebbe crisis, Peres was of the view that an attempt should be made to rescue the hostages who had been aboard an Air France airliner hijacked by Palestinian and German terrorists and diverted to Uganda. “It seemed clear we were more likely to mount a successful rescue than we were a successful negotiation,” he says.

Peres, in his capacity as minister of finance, had no qualms about dismantling the socialist framework of Israel’s economy. It was no longer viable, he argues. “We had to take our first steps toward capitalism.”

In explaining his views on the prospect of peace with its Arab enemies, Peres is unambiguous.

“I dedicated my life, first and foremost, to making sure Israel was secure,” he says. “When Israel was weak, I wanted to make her fierce. But once she was strong, I gave my life’s efforts to peace … knowing its achievement remains our most essential task.”

Inspired by Israel’s 1979 peace treaty with Egypt, he tried to forge peace with Jordan and the Palestinians. Having reached an agreement with King Hussein of Jordan in 1987, Peres took the plan to Yitzhak Shamir, the prime minister. Shamir, a hawk who was content with the status quo, was not interested in Peres’ dovish ideas. “It was a slap in the face to me personally, and a punch in the gut to the country I loved. Ben-Gurion … would have embraced the breakthrough. Shamir strangled it before it could have the chance to breathe.”

By his telling, Peres convinced Yitzhak Rabin, the prime minister, to change Israel’s strategy and enter into negotiations with the PLO. “No peace process can begin until enemies are first willing to engage with oner another,” he writes.

Rabin was skeptical of Jordan’s willingness to sign a peace treaty with Israel. But Peres was certain there was a deal to be made. He was right, of course. In 1994, Jordan became the second Arab country after Egypt to formally recognize, and end its state of belligerency with, Israel.

In the wake of the 1993 Oslo accords, Palestinian terrorists from Hamas and Islamic Jihad launched a series of devastating suicide bombings in Israel. “These conditions created an enormous leadership challenge for Rabin and me,” he says in an understatement.

Although he and Rabin had been bitter rivals, Rabin’s assassination in 1995 hit him hard. “It was like someone had attacked me with a knife, my chest laid bare, my heart punctured. I had forgotten how to breathe. I had just seen Rabin’s face, smiling like I’ve never seen before. There was so much life in him, so much hope and promise.”

Peres admits that suicide attacks by Hamas and Islamic Jihad in 1996 affected him badly. But he did not lose faith in the promise of peace. Oslo, he admits, fell short of his “grandest ambitions.” But it has produced “the foundations for a greater peace to come.”

He believes that the two-state solution, which has fallen on hard times under Netanyahu’s watch, is “the only framework that has a real chance to succeed.” Going one step further, Peres observes, “The future of the Zionist project depends on our embrace of the two-state solution. The danger, if Israel abandons this goal, is that the Palestinians will eventually accept a one-state solution.”

Peres’ words resonate, nearly two years after his death.