September marks the 80th anniversary of a World War II incident that could have gone badly awry and cost the lives of scores of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution.

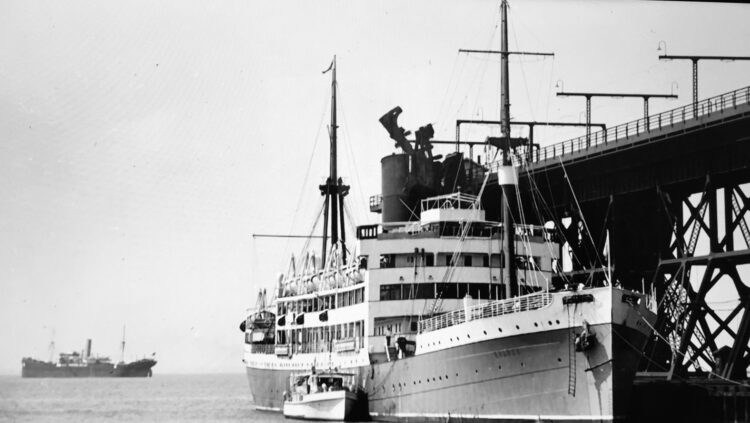

On August 8, 1940, the Portuguese vessel, the SS Quanza, set sail from Lisbon en route to New York City with 362 passengers, many of whom were Jews from Nazi-occupied Belgium seeking sanctuary in the United States. It remained to be seen whether the U.S. government would admit them.

Only a year before, hundreds of German Jewish refugees aboard the St. Louis had been turned away by Cuba, the United States and Canada, forcing some to return to Hamburg, Germany.

Laura Seltzer-Dun’s impassioned documentary, Nobody Wants Us, relates the saga of the SS Quanza through interviews with passengers, file footage and drawings. It initially will be broadcast on Cinemoi Television on Friday, September 25 at 10 p.m., EST, Saturday, September 26 at 6 p.m., EST, and Sunday, September 27 at 11 p.m., EST.

As Seltzer-Dun observes, Germany’s invasion of Belgium on May 10, 1940 sealed the fate of its Jewish citizens. “We knew the Germans were bad, but we had no idea how bad,” says Simone Neufeld, who was 13 when she and her family were forced to leave their home.

As German planes flew over Brussels on that fateful day, Annette Lachmann’s father realized that Jews had no alternative but to flee.

“The Germans were advancing and we were running,” recalls Irving Redel, who was 17 when these catastrophic events unfolded.

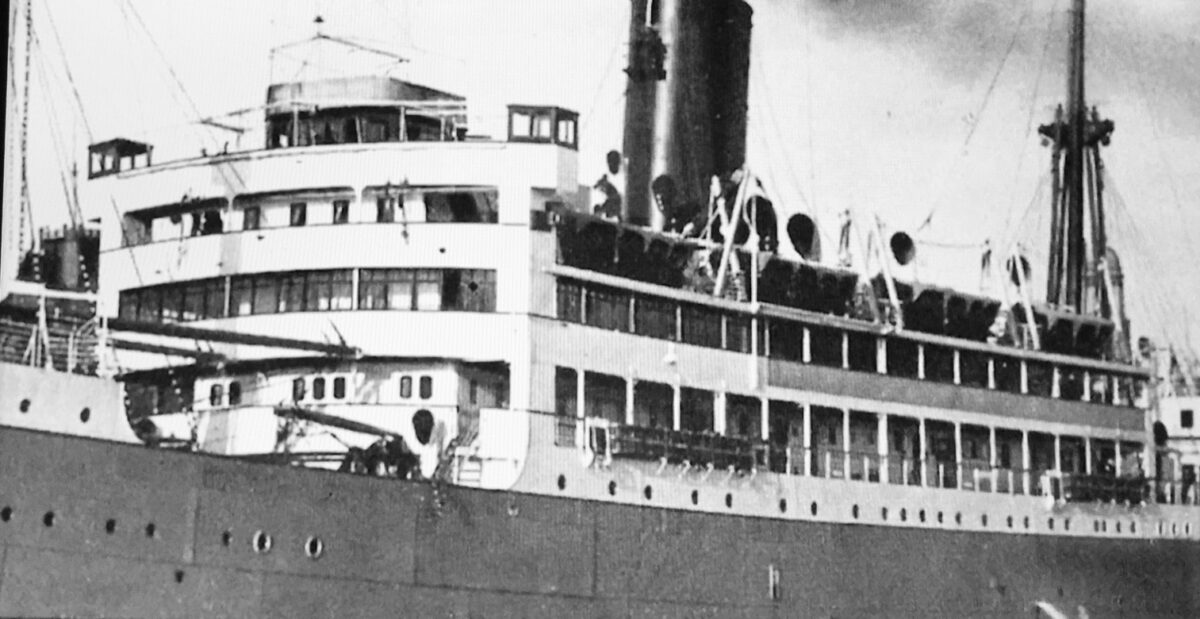

A group of Jews chartered the SS Quanza, a 5,000-ton ship that normally plied the waters of Africa from its home port in Lisbon, Portugal. Against the wishes of his government, the Portuguese consul-general in Bordeaux, France, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, issued visas to Jews who had bought tickets on the steamer.

They were required to purchase return tickets, even though it was understood that no one intended to go back to Europe. Since Portugal was neutral during the war, they could rest assured that the SS Quanza would not be torpedoed by German submarines.

Yet they were far from certain whether the United States would allow them to disembark in New York City. U.S. immigration policy, driven by xenophobia, antisemitism and a fear of Nazi infiltration, was restrictive. In 1940, less than 4,000 refugees were admitted.

“Nobody wanted us,” says Simone Neufeld after 121 passengers were denied entry to the U.S. after docking in New York.

The SS Quanza proceeded to Veracruz, Mexico. Thirty five passengers disembarked, leaving 86 on board, the majority of whom were Belgium Jews. “Everybody was in great despair,” says one of them.

The ship headed to Hampton Roads, Virginia, to buy coal for the voyage back to Lisbon. During the stopover, a local Jewish maritime lawyer, J.L. Morewitz, filed a lawsuit in federal court on behalf of the refugees and informed the Coast Guard that the ship was unseaworthy.

Morewitz’s strategy was to delay its departure so that American Jewish leaders, including Rabbi Stephen Wise of the World Jewish Congress, would have sufficient time to assist the refugees.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt approached the problem cautiously. He was sympathetic to their plight, but with a presidential election looming on the horizon, he did not want to be seen as pro-Jewish or soft on homeland security.

His wife, Eleanor, an advocate of child refugees, did not have such qualms. Having received a frantic telegram from the passengers, she asked Roosevelt to let them in.

The bigoted assistant U.S. Secretary of State, Breckenridge Long, vehemently objected to a humanitarian gesture.

But in the meantime, State Department official Patrick Murphy Malin was dispatched to Hampton Roads to study the matter. He recommended their admission into the United States.

Roosevelt’s decision saved lives, but precious few Jewish refugees were permitted to enter the United States after 1940.

Nobody Wants Us not only shines a light on this footnote, but makes the case for a liberal U.S. immigration policy at a moment when political currents are flowing in the opposite direction.

The film ends with a panel discussion during which its director, an immigration attorney, a Holocaust survivor and a passenger on the SS Quanza address these issues.