Four million Jews were murdered in German extermination camps or succumbed to hunger and disease in Nazi ghettos during the Holocaust.

A further two million Jews were killed by German firing squads, mainly in the Soviet Union and Poland. The cold-blooded shooters belonged to Einsatzgruppen mobile killing units and some 130 police battalions. Their overarching mission was to enforce Nazi tyranny in the occupied territories.

Ordinary Men: The Forgotten Holocaust, an absorbing 58-minute German documentary now available on Netflix, delves into this often overlooked aspect of the Holocaust by bullets. Its focus is on a police unit from Hamburg that carried out atrocities against men, women and children in the name of Adolf Hitler’s genocidal fascist regime.

The film, directed by Manfred Oldenberg, is partly based on historian Christopher Browning’s 1992 book, Ordinary Men: Reserve Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, which established him as one of America’s preeminent experts on the Holocaust. He appears quite frequently in this chilling movie, offering cogent commentaries on Germany’s ruthless campaign of antisemitic ethnic cleansing in Nazi-occupied Europe. His comments are supplemented by the remarks of German and American academics, file footage and reenactments.

The 500 young men who joined Battalion 101 hailed from all walks of life and were not particularly hostile to Jews or in thrall to Nazi racial theories. Some were even Social Democrats caught up in the swirl of events.

Their unit left Hamburg on June 22, 1942 after six months of training. This was nearly three years after the eruption of World War II and one full year after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Their assignment remained unclear until their arrival in the eastern Polish city of Lublin.

On July 13 of that year, the battalion’s commander, Major Wilhelm Trapp, informed them that their task was to shoot Jews at point-blank range. He told them they could drop out without major repercussions. Upon reflection, one policeman withdrew, prompting 12 more to do the same.

Although dissenters were not punished, they were often shunned and ostracized and assigned to clean toilets.

As Browning observes, the majority of policemen were not obsessed with Jews and were more concerned by the image they projected among their comrades. Yet many of them, having been influenced by the foulest form of Nazi ideology, did not even regard Jews as human beings.

At this point in the film, Oldenberg briefly dwells on the role of the Einsatzgruppen in the Holocaust. Composed of about 18,000 Jew haters and hardened killers, these units followed the Wehrmacht into the Soviet Union.

Their murderous rampage was supposed to be remain secret, but the German penchant for methodical record-keeping exposed the Einsatzgruppen to intense Allied scrutiny after the war. Benjamin Ferencz, a 27-year-old American Jewish lawyer from New York City, was placed in charge of bringing them to justice in a trial in western Germany in 1948. Ferencz, who died recently, speaks expansively about his experiences.

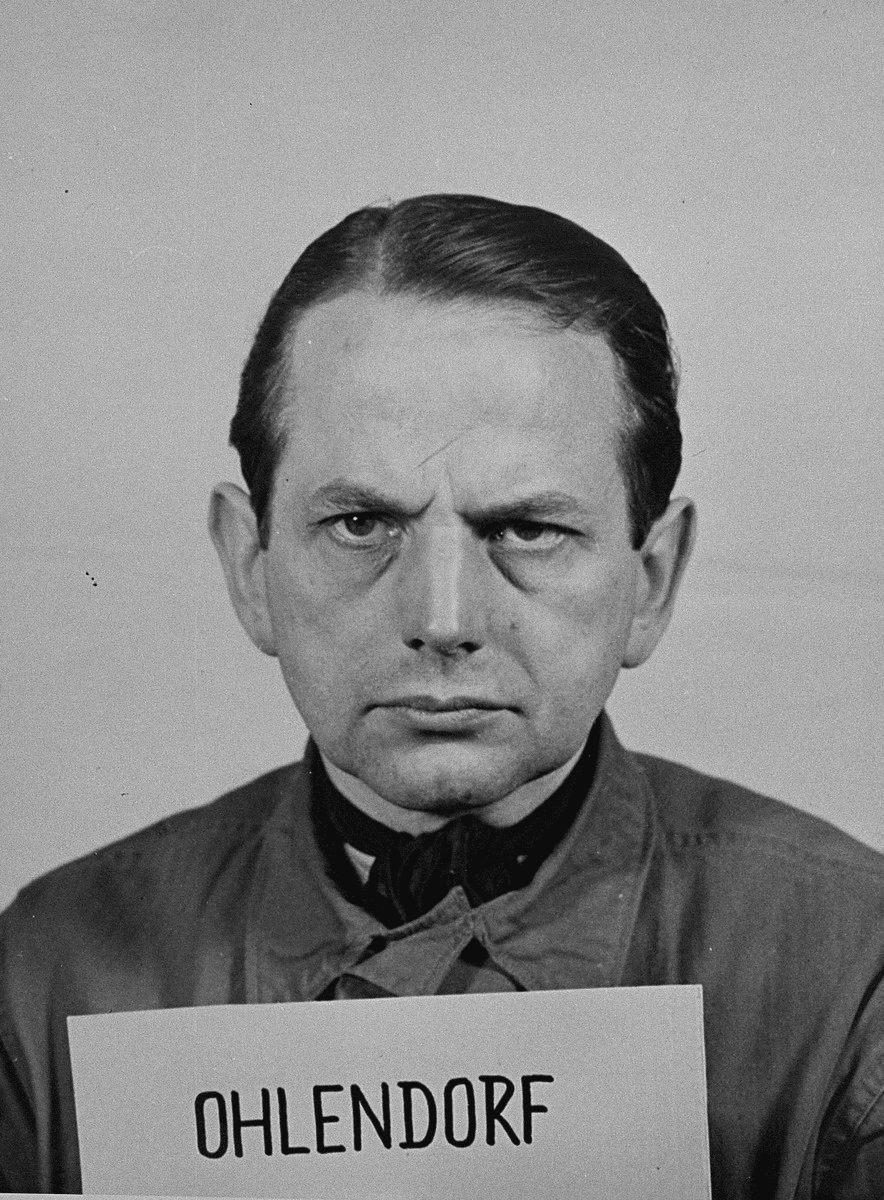

Among the 24 Einsatzgruppen commanders he prosecuted was Otto Ohlendorf, a suave, articulate, handsome, seemingly decent, and superbly educated German whose squad hunted down and murdered 90,000 Jews in 1942.

As Ferencz would learn, Ohlendorf, a fierce German nationalist from a Nazi family, fervently believed that Jews were responsible for grafting communism on Russia and had to be eliminated.

Segueing back to Battalion 101, Oldenberg points out that some of its recruits were so demoralized and traumatized by the gruesome job they performed that they asked for transfers. Others silently complied without protest. Still others actually enjoyed their work.

Upwards of 60,000 policemen were involved in the deaths of 38,000 Jews and in the transport of 45,000 Jews to Nazi extermination camps in Poland. A further 172,000 Germans in the SS and Gestapo had a direct role in the implementation of the Holocaust.

Only five percent of these morally tainted individuals were convicted of war crimes.

Ironically enough, many regarded themselves as victims and were consumed by self-pity rather than guilt. “My men suffered more than the victims,” claimed Ohlendorf, who was hanged in 1948 without ever having expressed regret or remorse.

In closing, Browning maintains that people are capable of descending into the depths of depravity and becoming murderers, cogs in the machinery of death. Another historian argues that a murderer does not have to be hateful or ideological in order to kill.

Human beings are malleable and vulnerable and can be programmed to commit crimes they could not even have imagined.

Since the Holocaust, crimes against humanity have been committed in, among other places, Rwanda and Srebernica.

So the business of ethnic cleansing continues unabated, more than 75 years after German policemen callously murdered Jews in Eastern Europe.