It’s hard being anything but a particular kind of Sunni Muslim in Pakistan these days.

Christians, Hindus, Shia Muslims and members of the Ahmadiyya sect — considered heretical by many other Muslims — are wise to remain circumspect.

Even adherents of Sufi orders, most of them Sunnis, are considered idolaters by Salafist fundamentalists. All these groups are the victims of periodic outbursts of violence and even murder.

The country, which since 1971 includes only what used to be West Pakistan, is overwhelmingly Muslim — only about five percent of its 190 million people are Christians or Hindus.

Shia Muslims, often also considered heretics by extreme Sunni groups, comprise upwards of 20 per cent of the country’s Muslim population. The Ahmadiyya are at most some two percent.

When Pakistan was created during the partition of the Indian subcontinent, relations between the two major branches of Islam were fairly amicable, and many of the country’s initial leaders were Shia. They were elected to top offices and played an important part in the country’s politics. The founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, was an Ismaili who converted to Twelver Shiism.

But this began to change in the late 1970s, especially after the April 1979 execution of deposed former president Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a Shia, by General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, a devout Sunni.

Zia’s Sunni Islamization campaign emboldened sectarian radicals, but his laws and regulations were resisted by Shia who saw it as “Sunnification” of the political system.

Also, a new generation of Shia activists found inspiration in the assertive Shiism of Ayatollah Khomeini’s post-1979 Iran, Pakistan’s western neighbor. In July 1980, 25,000 Shia protested in the Pakistani capital, Islamabad.

Sectarian radical Sunnis, inspired by Saudi Arabia and Gulf states, now began to preach against the Shia, and terrorist groups sprang up. Their growth is widely attributed to those countries having provided millions of dollars of funding to these fundamentalist networks.

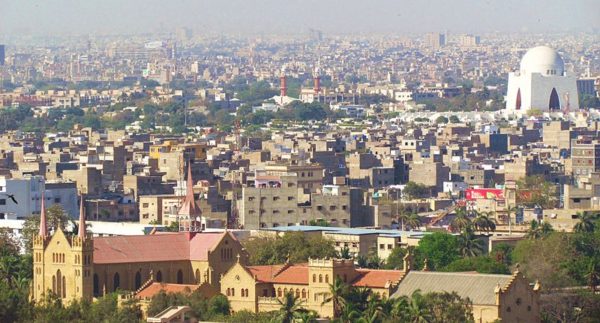

Sectarian riots broke out in 1983 in Karachi, Pakistan’s major city, and spread to other centres, including Lahore.

Since 2008, Pakistan’s Shia Muslim community has been the target of an unprecedented escalation in violence as Sunni militant groups such as Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, Sipah-e-Sahaba, and Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan have killed thousands of Shia across the country — more than 2,000 just since 2015.

Yet many of the leaders of these networks, though charged with mass murder, continue to avoid prosecution or otherwise evade accountability. After all, many were initially aided, even created, by the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI), Pakistan’s national security directorate.

Sufis overlap the sectarian divide, though most are Sunnis. They practice a more mystical form of Islam and venerate holy men who, they believe, serve as conduits to God, and pray at the shrines where these devout men are buried. Pakistan’s two most populous provinces, Sindh and Punjab, comprise a dense archipelago of shrines devoted to these men.

For extremists, this amounts to idolatry and “grave-worship.” Since March 2005, 209 people have been killed and 560 injured in 29 different terrorist attacks targeting shrines and tombs devoted to Sufi “saints.”

On February 17, an Islamic State supporter struck a crowd of Sufi dancers celebrating in the Pakistani shrine of Sehwan Sharif. The attack killed almost 90 worshippers.

The militants have undermined what Shahab Ahmed, in his book What is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic, calls the “philosophical-Sufi amalgam,” the loss of which has harmed Pakistan

Ahmadis were declared non-Muslims through a constitutional amendment passed in 1974, the same year that hundreds were slaughtered in riots. A few years later, a new law was brought in barring Ahmadis from calling their places of worship mosques or from propagating their faith.

Many more have perished since then, including 94 people killed by the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan in attacks in Lahore in 2010. In April, an Ahmadi professor was found stabbed to death in her house in Lahore, one of three killed that month.

Pakistani support and encouragement of Ahmadi persecution is visible in the passport application form that every Pakistani citizen needs to fill in. The application requires all Muslim citizens to sign a declaration affirming that they consider Ahmadis as infidels.

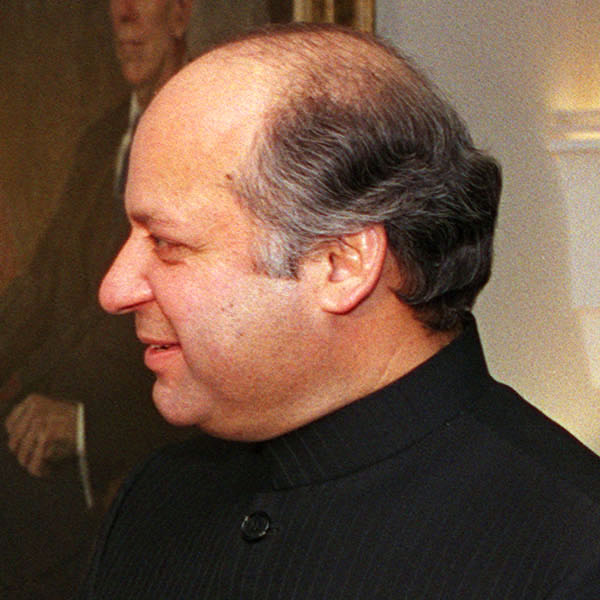

In December of last year, Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif renamed the National Center for Physics at Quaid-e-Azam University in Islamabad for physicist Abdus Salam, the country’s first Nobel laureate. He had been ignored for more than 30 years because he had belonged to the Ahmadi sect.

But many groups have opposed the decision and demanded the prime minister retract it. Sharif was also denounced two months earlier for his warm remarks to Pakistani Hindus during the festival of Diwali.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.