More than ten days have elapsed since the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan was shaken by allegations that King Abdullah II’s estranged half brother, Prince Hamzah bin Hussein, was involved in a plot to undermine the government.

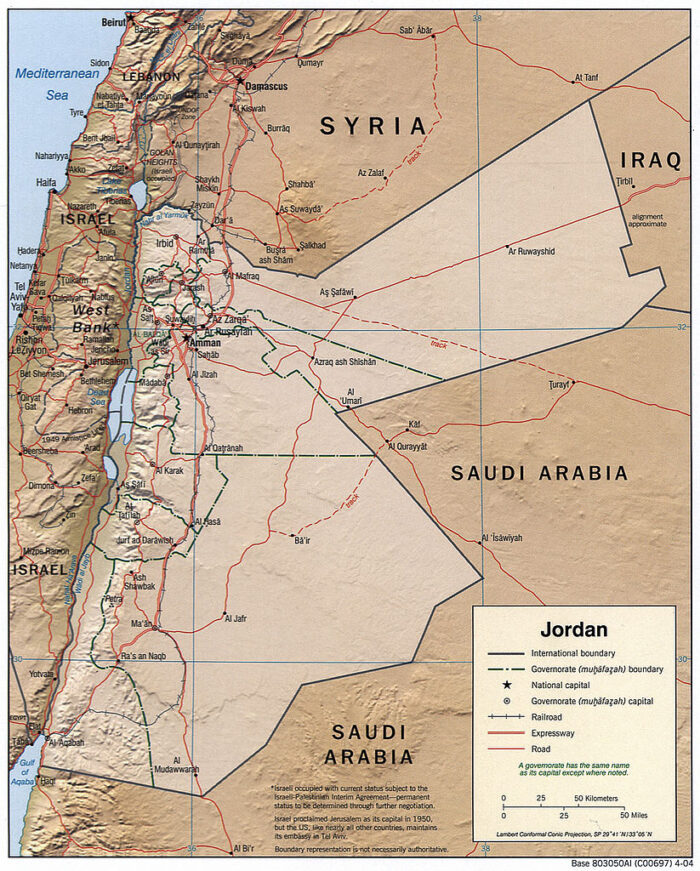

In the hours after this news rocked Jordan, a beacon of stability in the Middle East for the past 50 years, the Jordanian foreign minister, Ayman Safadi, accused the prince — a brigadier-general in the Jordanian army — and several of his associates of “incitement and efforts to mobilize citizens against the state in a manner that threatens national security.”

Firing back with two videos, the prince stoutly denied the accusation, issued a critique of the country’s “corrupt and intolerant” leadership, and disclosed he had been placed under house arrest. His mother, Queen Noor, released a stinging statement claiming her son was the victim of “wicked slander.”

No sooner had this palace feud erupted than it faded away, leaving observers in the dark as to what had transpired in Amman from April 4th onward. We may never really know exactly what happened.

These events occurred as Jordan — an ally of the United States and the second Arab state to sign a peace treaty with Israel — was busy coping with ongoing pressing challenges.

The coronavirus pandemic has killed 8,000 Jordanians and contributed to a dismal high unemployment rate. And the influx of 630,000 Syrian refugees since the outbreak of the civil war in Syria in 2011 has enormously strained Jordan’s economy, which is dependent on foreign aid.

The crisis, which temporarily shattered the outward calm that Jordan normally projects, was deftly defused by Prince Hassan, the late King Hussein’s brother. As a result of his intervention, the prince pledged loyalty to the king, ending a rare but embarrassing public rift within Jordan’s first family.

In an anodyne statement from the royal court bearing his signature, the prince said, “The interest of the nation comes above all else and we should all stand behind His Majesty in his efforts to protect Jordan … In light of the developments of the past two days, I put myself in the hands of the king.”

On April 7, a newscaster on television read a statement by the king addressed to the Jordanian people. Announcing that the prince’s “sedition had been nipped in the bud,” the king said that his half-brother had agreed “to put Jordan’s interest, constitution and laws above all considerations, and that he and his family were “under my care.”

The king added, “The challenge over the past few days was not the most difficult or dangerous to the stability of our nation. But to me, it was the most painful.”

Disclosing that the prince’s associates “are under investigation, in accordance with the law,” the king said that their cases would be handled “in a manner that guarantees justice and transparency.” He was referring to, among others, Bassem Awadallah, the former finance minister, and Sharif Hassan bin Zaid, a member of the royal court and a former ambassador to Saudi Arabia.

Four days later, on April 11, the king released a photograph of himself, Crown Prince Ali Hussein bin Abdullah II, the prince and other members of the royal family at the grave of King Talal, who briefly ruled Jordan after the assassination of King Abdullah I in East Jerusalem in 1951.

The ceremony at which they appeared marked the centenary of the formation of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate. Jordan won its independence from the British in 1946 and has since been in the Western camp.

The seeds of this long-simmering feud between the king — the son of King Hussein’s second wife, Princesses Muna — and the prince — the son of King Hussein’s fourth wife, Queen Noor — were planted years earlier.

King Hussein, a direct descendent of the Prophet Mohammed, ruled Jordan for decades after the abdication of his father, King Talal, in 1952. Before King Hussein’s death in 1999, he appointed his son, Abdullah II, an army officer, as his successor, thereby demoting Prince Hassan, who had been crown prince since 1965.

King Abdullah II named Prince Hamzah bin Hussein as crown prince shortly after King Hussein’s death. But in 2004, he transferred the title to his son, Prince Ali Hussein bin Abdullah II, an officer in the army.

Such maneuvers are not uncommon in Jordan. In 2017, the king relieved his brother, Faisal, and his half-brother, Hashim, of their respective commands in the armed forces.

The prince accepted his demotion with apparent stoicism. But in recent years, he began to rebuild his position, taking to social media to condemn the government as incompetent, corrupt and authoritarian and to call for real change. “Oh, my country,” he lamented in a post.

The prince maintained close contact with Jordan’s tribal leaders, a pillar of the monarchy, leading to fears within the palace that he was trying to unseat the king.

This tawdry episode has tarnished Jordan’s reputation. Once regarded as a fairly enlightened nation, Jordan is increasingly perceived as just another authoritarian Arab state.

According to Freedom House, a U.S.-based organization that monitors democracy, political freedom and human rights, Jordan’s status since 2020 has plummeted from “partly free” to “not free.”

As an observer recently wrote in the magazine Foreign Affairs, the king has been reluctant to phase in meaningful political reforms, while his economic reforms have produced “more allegations of corruption than positive economic results.”

Since 2011, when the region was convulsed by the Arab Spring chain of rebellions that unseated autocrats in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Yemen, protests have erupted in Jordan due to worsening living standards. The monarchy has tried to defuse discontent by means of subsidies, wage increases and a reshuffling of leadership. Since 1999, the king has appointed no less than 13 prime ministers.

But Jordan has not been loathe to crack down on unacceptable dissent through harassment, threats and arrests.

Despite the recent turmoil, Jordan is still one of the most stable countries in the Middle East. Jordan was wracked by instability in the late 1950s and by a short civil war in 1970 after King Hussein decided to expel the PLO, which had established a state-within-a-state on its soil after the 1967 Six Day War.

Ever since then, Jordan has been an oasis of stability in a turbulent area. The clash between the king and the prince, though fairly serious, was probably little more than a tempest in a teapot.