The first Palestinian Arab rebellion in Palestine broke out in 1936 and flickered out in 1939. It would be the final revolt of its kind during the British Mandate era, but hardly the last Palestinian uprising.

Two more revolts erupted long after the birth of Israel, the first in 1987 and the second in 2000. While they are still relatively fresh in the minds of Israelis and Palestinians, the 1936 uprising has virtually receded from memory due to the passage of time and the dearth of books about it in Hebrew, Arabic and English.

Oren Kessler, an Israeli journalist, has filled the gap admirably with Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict (Rowman & Littlefield), which he describes as the first general-interest volume outside academia of that tumultuous event. A lucid writer, he deals not only with the revolt itself — the first major clash between the Zionist and the Palestinian national movements — but also delves into its causes and legacy.

Kessler provides readers with a thorough and thoughtful history of Palestine before addressing the theme at hand.

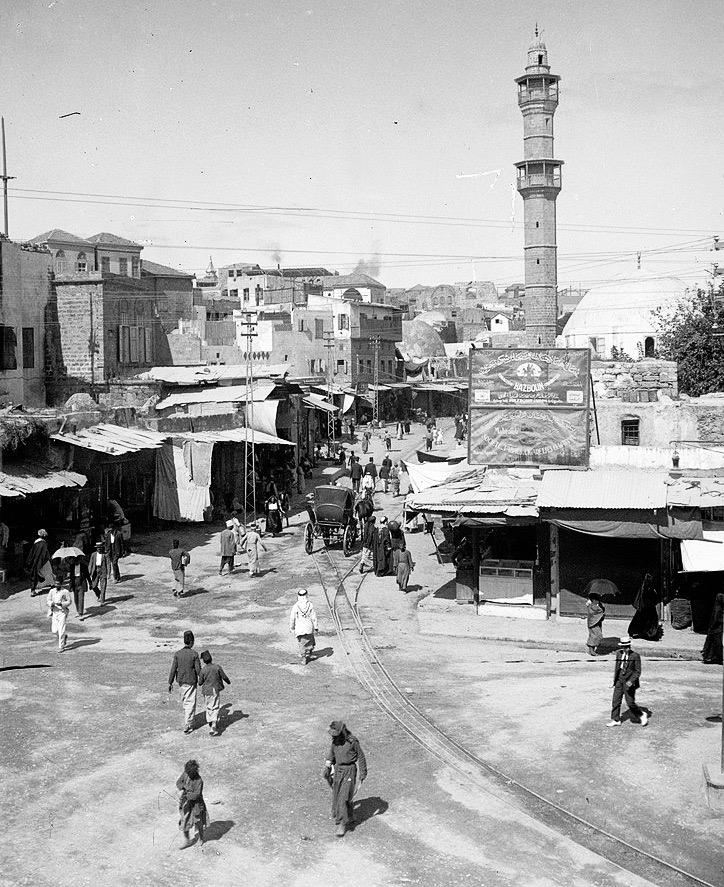

May Day rallies in Jaffa in 1921 degenerated into Arab-Jewish riots throughout the country, the first mass-casualty explosion in British-controlled Palestine. A commission of inquiry concluded that Palestinian fury was rooted in fears of Jewish demographic, economic and political domination.

This was followed by a report in 1922 reaffirming Britain’s commitment to the 1917 Balfour Declaration, which envisioned a Jewish homeland in Palestine, but rejected the idea of a Jewish state there.

Tensions subsided, and in the absence of violence, the Zionist leadership concentrated on developing the Jewish economy and building rural settlements. During this lull, the Hebrew University on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem was inaugurated, Jewish land purchases from absentee Arab owners doubled, and 80,000 Jewish immigrants arrived.

Mainstream Zionists hoped that a climate of prosperity would induce the Palestinians to come to terms with Zionism. Vladimir Jabotinsky, who would be the leader of the right-wing Zionist Revisionist movement, thought that Zionists should be more forthcoming about their real objective. In his seminal 1923 essay, The Iron Wall, he spelled it out clearly: Jews sought statehood, not merely autonomy, in Palestine.

This was precisely the appraisal of the Supreme Muslim Council, the leading Palestinian political organization. It was led by Hajj Amin al-Husseini, who had been appointed mufti of Jerusalem by Herbert Samuel, Britain’s first and only Jewish high commissioner in Palestine.

A new wave of bloodshed broke out in 1929 when Arab terrorists attacked the Jewish community in Hebron, killing 67 of its residents. In short order, the violence spread to the rest of the country, resulting in more than 200 fatalities.

Four years later, the Palestinians conducted their first general strike, a one-week work stoppage aimed at the British.

Despite the turbulence, Jewish and Arab leaders engaged in informal talks. In 1934, David Ben-Gurion and Moshe Shertok (Sharett) met Musa Alami, a Palestinian activist and civil servant, in Jerusalem. Alami was disappointed to learn that Zionists sought a state within an Arab federation. He had assumed their goal was simply a national homeland, as defined by the Balfour Declaration. He suggested a form of Jewish autonomy, around Tel Aviv, within an Arab federation under British guardianship.

To their argument that the Palestinians stood to gain economically from the Zionist project, Alami replied that he preferred Palestine to remain desolate and poor for another century until the Arabs could develop it themselves.

By that point, Tel Aviv’s population had tripled, the country’s Jewish-dominated industrial, banking and construction sectors flourished, and nearly 400,000 Jews lived in Palestine. These were unacceptable developments for the Palestinian leadership, which demanded an end to Jewish immigration, a prohibition on land sales, and the establishment of a representative government reflecting the Arab majority.

The immigration of Jews to Palestine was actively promoted by antisemitic governments in Poland and Romania, both of which sought to reduce their respective Jewish population. Indeed, the Polish ambassador in London pressed Britain to relinquish Palestine to the Zionists.

By Kessler’s reckoning, the 1936 rebellion got under way on April 15 when Israel Hazan, a recent Greek immigrant from Salonica, was killed by Arabs in the West Bank. The following night, two Jews murdered Hassan Abu Rass, an Arab fruit picker, near Petah Tikvah. He and Hazan were the first victims of the Great Arab Revolt, which would be known in Arabic as al-Thawra al-Arabiya al-Kubra.

The violence spilled over into Jaffa, claiming the lives of 16 Jews and five Arabs. Two days before this calamity, Ben-Gurion met George Antonius, a Christian Palestinian activist, Anglophile and government employee who would write the classic work The Arab Awakening.

Antonius favored Arab-Jewish understanding, but insisted that Zionist and Palestinian aspirations were irreconcilable and that Jews should be satisfied with nothing more than a “spiritual center” in Palestine. In his view, there was no room for “a second nation in a country which is already inhabited … by a people whose national consciousness is fully awakened, and whose affection for their homes … is obviously unconquerable.”

Shortly afterward, the Palestinians’ national council, the Arab Higher Committee, declared a general strike. “Ben-Gurion sensed an opportunity,” Kessler writes. “He had spent years promoting separate, self-sufficient Jewish agricultural and industrial sectors that would be freed from a dependence on less expensive Arab labor.”

Ben-Gurion exploited the strike by opening a port in Tel Aviv and by building a Jewish self-defence force that could withstand an Arab onslaught.

The new harbor, a few kilometers from the Arab port of Jaffa, would be manned by Jewish dockworkers from Greece. Jaffa oranges, Palestine’s biggest export, would be shipped through it to European markets.

Orde Wingate, a British army intelligence officer and a distant cousin of T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), took the first step in fulfilling Ben-Gurion’s dream of a Jewish army.

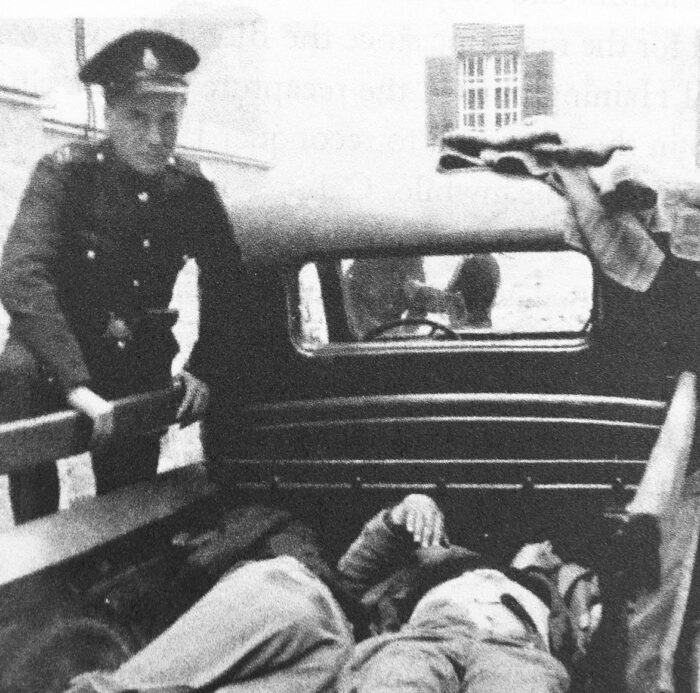

Posted to Palestine in 1936, Wingate was a fervent Christian Zionist who created the Special Night Squads. Composed of Jewish recruits, they were designed to combat Arab insurrectionists, one of whose commanders was Fawzi al-Qawuqji. The Wingate units constituted a major British response to the nation-wide Arab rebellion against British forces and Jews.

As well, Britain placed Palestine under martial law and mounted a counterinsurgency campaign that enabled it to impose curfews, arrest suspected terrorists without warrants, seize arms, deport rioters, and reinforce its already substantial garrison.

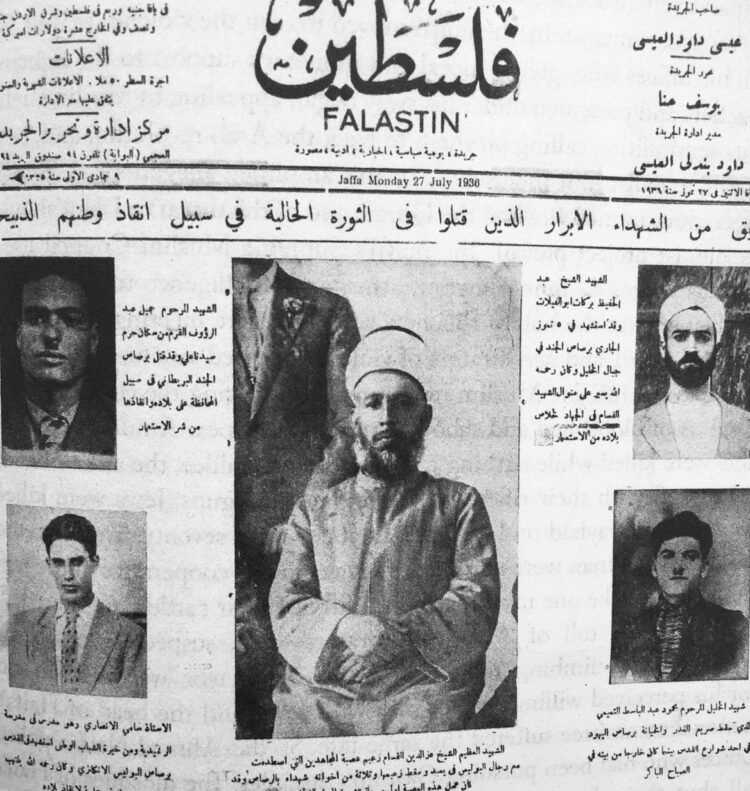

The rebellion, which united rival Palestinian families in a single struggle, gained momentum. In July 1938, some 60 Jews and well over 100 Arabs were killed, in the bloodiest month of the uprising. Palestine was now in “open rebellion,” as the British high commissioner, Harold MacMichael, noted.

Fascist Italy, in part, funded the rebellion, but the Italians were playing a double game. In 1934, the Italian leader, Benito Mussolini, twice met Chaim Weizmann, the president of the World Zionist Organization. Mussolini was indifferent to Zionism, but he was prepared to use every opportunity to erode British power in the Mediterranean basin.

Although Britain cracked down hard on Arab insurrectionists, the British government began to consider the possibility of partitioning Palestine into Jewish and Arab enclaves, notwithstanding the fact that Jews owned only seven percent of its lands.

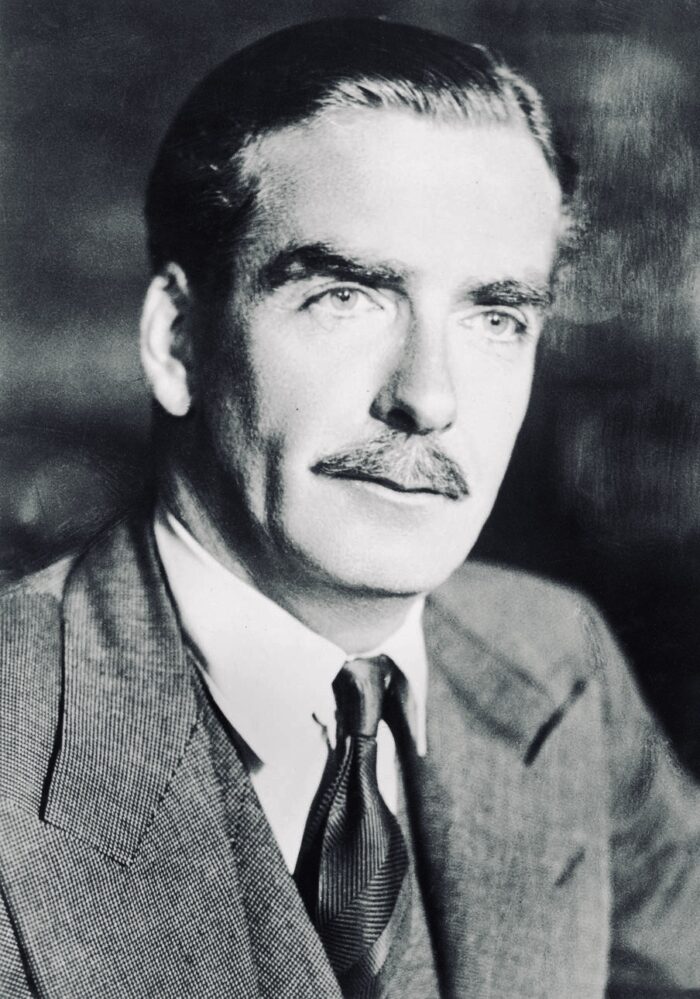

British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden opposed partition, saying it was vehemently opposed by the Palestinians and contravened Britain’s interests. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain backed Eden, arguing that partition would antagonize the Arabs and permit fascist powers to exploit Palestinian outrage.

Malcolm MacDonald, who was appointed secretary of state for the colonies in the spring of 1938, admired Zionist enterprise in Palestine, but was determined to “radically change our outlook on the Palestine problem.”

On May 17, 1939, a few months before the outbreak of World Wear II, he presented a White Paper which shocked Zionists, but which did not mollify Arabs. Fearing that the influx of Jews into Palestine and the continuance of Jewish land purchases exacerbated Arab-Jewish enmity at a moment when Britain required Arab friendship, he drastically restricted Jewish immigration and land sales. And in a stunning blow to Zionists, he recommended that the Mandate should be replaced by an independent “Palestine state” within a decade.

MacDonald, in an unpublished memoir, said he had drafted certain portions of the White Paper with tears in his eyes. And yet, he added, he could not allow emotion to rule his thinking.

The White Paper, though mostly favorable to Arab interests, did not impress Hajj Amin al-Husseini, the virtually undisputed leader of the Palestinian cause. Now exiled in Lebanon, he took refuge in Iraq and Italy before settling in Berlin. It was there that he met Adolf Hitler, who assured him that “the destruction of the Jewish element” in Palestine was one of Nazi Germany’s objectives in the Middle East.

Husseini believed Hitler. As he put it, “I was certain that if Germany and the Axis had been victorious, no trace of the Zionists would have remained in Palestine and the Arab lands.”

While residing in Berlin, Husseini proved useful to Germany, helping SS chieftain Heinrich Himmler form two Muslim army divisions and regularly appearing as a propagandist on Nazi radio.

Judging by Husseini’s racist comments, he was not only an anti-Zionist, but an antisemite. Parroting the Nazi party line, he said that Jewish “character traits make them incapable of keeping faith with anyone or of mixing with any other nation.” Warming up to this theme, he claimed that Jews live “as parasites among the peoples, suck their blood, steal their property, pervert their morals, and yet demand the same rights that the native inhabitants enjoy.”

Husseini lived long enough to witness the failure of the 1936 revolt, which claimed the lives of anywhere from 5,000 to 8,000 Arabs, about 500 Jews and around 250 British soldiers and police, and resulted in the departure of 40,000 Arabs from Palestine.

It is true, as Kessler acknowledges, that the rebellion prompted the retreat of the British from the Balfour Declaration. But in all other respects, it proved disastrous for the Palestinians. “Arab Palestine’s fighting capacity was debilitated, its economy gutted, and its political leadership banished,” he says. “The revolt to end Zionism had instead crushed the Arabs themselves, leaving them crippled in facing the Jews’ own drive for statehood a decade on. It was the closest the Palestinians would ever come to victory.”

Kessler convincingly argues that the Jews of Palestine consolidated the demographic, geographic and political basis of their state during this period rather than in 1948, when the first Arab-Israeli war broke out.

And he contends that the uprising ultimately persuaded Britain that its mandate in Palestine was too costly and unsustainable.

In the wake of the United Nations’ 1947 Palestine partition plan, the Haganah, the Jewish defence force, and Palestinian militias clashed in battles in, among other places, Jaffa, Haifa, Tiberias and Safad. The Zionists, far more politically and organizationally unified than the Arabs, emerged victorious.

Just hours before the Mandate expired, Israel declared statehood, unleashing an Arab invasion of the new Jewish state that the Israeli armed forces ultimately managed to repel.

The revolt was the first real Palestinian intifada, and while it failed, it marked the beginning of a protracted armed struggle that shows no signs of abating, judging by the latest Israel-Gaza cross-border fighting.