Ninety five years have elapsed since world leaders gathered in Paris to create a new international order following the carnage of World War I — the “war to end all wars.” The Paris Peace Conference, a momentous event, is expertly examined by Margaret MacMillan in Paris 1919 (Random House).

France’s foray into fascism and state antisemitism, just 20 years later, is the subject of another book, Frederick Brown’s The Embrace of Unreason: France, 1914-1940 (Alfred A. Knopf).

MacMillan, a distinguished Canadian historian, reminds readers that World War I– which erupted a century ago last month and toppled governments and empires — claimed the lives of millions of soldiers, including 1.8 million Germans, 1.7 million Russians, 1.3 million French, 1.2 Austrians and Hungarians and 743,000 British.

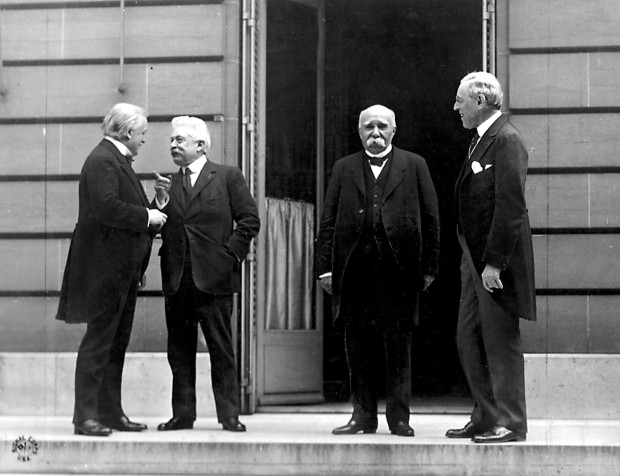

By her reckoning, the most important decisions were taken between January and June 1919, though officially, the conference lasted well into 1920. The key decision makers were Georges Clemenceau, Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, respectively the prime ministers of France, Britain and Italy, and Woodrow Wilson, the president of the United States.

As MacMillian points out, their first priority of business was whipping up the Versailles Treaty, which settled Allied claims against Germany. But statesmen in Paris were also called upon to draw new borders in Europe and form a peacekeeping organization, the League of Nations.

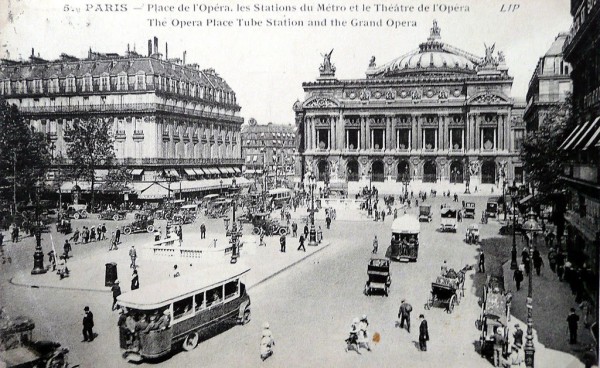

Europe, in that year, was in free fall economically. Millions were unemployed. Hundreds of millions faced famine. Trade had to be revived. It would take Europe until 1925 to return to pre-war levels of production. But in Paris, in the winter, spring and summer of 1919, life was good for the moneyed. As she puts it,”The restaurants, when they could get supplies, were still marvellous. In the nightclubs, couples tripped the new fox-trots and tangos. The weather was surprisingly mild. The grass was green and a few flowers still bloomed.”

Despite the city’s allure, neither Britain nor the United States had been keen about holding the conference in Paris, believing that a just peace could not be signed in the capital of a country that bore so much animosity toward its historic rival, Germany.

Indeed, as MacMillan observes, France, of all the great powers, had the most at stake in the proceedings. “France not only had suffered the most; it also had the most to fear. Whatever happened, Germany would still lie along its eastern border. There would still be more Germans than French.”

As a result, she adds, France pushed for toughest possible terms against Germany.

But as pivotal as the conference would be in the post-war era, a number of geopolitical issues were already being settled by the time peacemakers arrived in Paris.

Poland, having emerged as a sovereign nation after more than a century of foreign subjugation, fought six wars from 1918 to 1920 to ensure its independence. Finland, the Baltic states and what would be Czechoslovakia were heading toward nationhood. A Yugoslavian state was emerging from the wreckage of Austria-Hungary’s South Slav territories. And following the collapse of the Russian monarchy, 180,000 troops from Japan, Britain, Canada and the United States landed troops in Russia to fill the vacuum.

Of all the victors at the conference, she says, Romania made by far the greatest gains, doubling in size and population. Apart from wresting away Bessarabia and Bukovina, parts of which it would lose to the Soviet Union after World War II, Romania seized Transylvania. Among the defeated nations, Hungary fared the worst, losing two-thirds of its land and people under the Treaty of Trianon.

The fate of the Ottoman Empire was largely decided outside the framework of the conference. During the war, Britain, France and Russia had unilaterally divided this Muslim empire among themselves, and Britain had promised the Zionist movement, headed by Chaim Weizmann, a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

League of Nations mandates were established in Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq. Kurdish aspirations for statehood, having been accepted under the Treaty of Sevres, were conveniently brushed aside under the Treaty of Lausanne. Turkey, led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, carved out a separate nation in Anatolia and engaged in population exchanges after a war with Greece.

Germany, having been decisively beaten on the battlefield, lost Alsace-Lorraine and would have to endure the occupation of the Rhineland. But the issue of reparations caused the most trouble. “The new Weimar democracy started life with a crushing burden, and the Nazis were able to play on understandable German resentment,” writes Macmillan.

Britain, seeking stability in Europe, as well as a market of 70 million Germans for its manufactured goods, had argued that peace terms should not destroy Germany. France, however, countered that the Germans could not be appeased.

Germany, at the signing ceremony in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles on June 28, 1919, was forced to accept sweeping concessions that threw Germans into mourning. “Nationalists blamed the traitors at home who had stabbed Germany in the back, and the governing coalition which had signed the treaty,” she says.

Eventually, public opinion in Britain and the United States came around to the view that Germany had been treated too harshly. But according to MacMillan, “the picture of a Germany crushed by a vindictive peace cannot be sustained.”

Germany’s strategic position improved after 1919, and the Treaty of Versailles was never consistently enforced, she adds. With the triumph of the Nazis in 1933, Germany inherited a government bent on destroying the treaty.

MacMillan, in her usual thorough fashion, places these events into their proper context in Paris 1919, a book of substance and grace.

***

In The Embrace of Unreason, Brown, a specialist on France, skillfully explores the corrosive social and political forces that brought the country to a nadir. Through the lives of right-wing French intellectuals like Maurice Barres and Charles Maurras, he explains how France swivelled from the traditions of enlightenment and humanism to xenophobia and racism.

For Barres, a dyed-in-the-wool antisemite, the Alfred Dreyfus affair was the defining event that completed his radicalization and distorted vision of Jews.

“Jews have no fatherland in the sense we ascribe to the word,” he wrote. “For us, the fatherland is in the soil of ancestors, the earth of our dead. For them, it is wherever they find their greatest interest.”

As leader of the royalist and anti-Jewish movement L’Action Francaise, Maurras “contributed in no small measure to the brutalization of French political life between the world wars,” Brown writes.

They were the godfathers of Vichy France, which irretrievably tarnished France from 1940 to 1944.