Upon arriving at Ben-Gurion Airport on the night of December 30, 2020, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, the convicted spy Jonathan Jay Pollard was greeted on the tarmac by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who was wearing a long black coat and a mask. Before formally acknowledging Netanyahu, Pollard made a slight motion with his hand, removed his mask, bent down stiffly and kissed the ground, thrilled to be in Israel, the nation for which he had devoted the best years of his life.

Pollard’s frail second wife, Esther, performed the same ritual, albeit more awkwardly.

Pollard, a Jewish American who had volunteered his services to Israel as a spy, landed in the Jewish homeland as a hero. But to the United States, Israel’s chief ally, Pollard was nothing less than a traitor. Until his flight to Israel, he had been a prisoner, having served a 30-year sentence, plus an additional five years outside of jail under severe restrictions.

In his capacity as a U.S. Navy intelligence analyst, Pollard turned over a mountain of top-secret American documents to his Israeli handlers. Many of them related to Arab military capabilities and were therefore of enormous value to Israel. Pollard thought that the United States should have given this intelligence to Israel voluntarily.

Pollard’s illicit activities, which were known to only a handful of officials in Israel, created an unprecedented crisis in Israel’s strategic relationship with the United States.

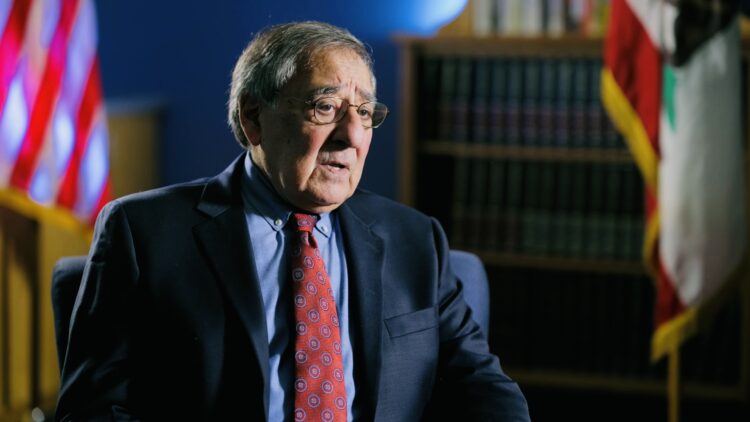

“You don’t expect a friend and an ally to spy on you,” says Leon Panetta, the former U.S. secretary of defence. According to Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s two-time prime minister, the Israeli government made a “serious” and a “major” mistake in collaborating with Pollard.

Their comments surface in Pollard, a first-rate documentary by Omri Assenheim that unfolds in four episodes on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform. It will be available from February 15 onward.

Assenheim’s incisive film takes a viewer from Pollard’s youth in South Bend, Indiana, where his father was a professor of microbiology at Notre Dame University, to his betrayal of the United States. Israeli and U.S. officials fill in the gaps with pertinent information.

Classmates remember Pollard as a different, withdrawn and academically gifted student who was bullied. Some of the taunts directed at him were antisemitic. This was hardly surprising in a city where Jews were barred from joining a local country club.

Pollard was a teenager when the Six Day War broke out. While he feared that Israel might be defeated, he was elated by Israel’s conquest of Arab territories. His interest in Jewish affairs was heightened by a visit to Dachau, the former concentration camp in Germany, when he was 14 years old.

As one classmate and an official from a major Jewish organization recall, he dreamed of spying for Israel and becoming a Jewish James Bond who would “save” the Jewish people. While studying at Stanford University, Pollard, a heavy drug user, claimed he was employed by the Mossad. On another occasion, he told someone he had studied at Harvard University. Pollard was clearly a fantasist and a liar.

After the Central Intelligence Agency rejected his job application, Pollard was hired by the U.S. Navy as an intelligence analyst. His access to sensitive documents was temporarily downgraded after he offered his expertise to the apartheid South African government.

As Assenheim suggests, he reached a turning point in his life when he was introduced to Aviem Sella, a renowned Israeli Air Force pilot on sabbatical at New York University. Pollard volunteered to give Sella documents on Israel’s Arab enemies. Sella, who would be one of Pollard’s contacts, gladly accepted his offer.

Eventually, Pollard would be in close touch with several Israeli officials: Yossi Yagur, Sella’s superior; Ilan Ravid, the science attache at the Israeli embassy in Washington, and Rafi Eitan, one of the founders of the Mossad and the director of the Bureau of Scientific Contacts, or Lakam.

According to Yagur, Pollard’s highly classified material was “out of the world” and could fill a large room. At one point, Pollard demanded more money from Israel so as to maintain his lavish lifestyle.

“He wanted to be seen as a great hero of Israel,” says James Olson, the former head of the Central Intelligence Agency’s counter-intelligence unit.

Although Eitan gave Pollard an Israeli passport under the name of Eli Cohen, as well as a monthly stipend of $1,500, he apparently kept a lot of his colleagues out of the loop regarding his association with Pollard. Olson believes that Eitan acted foolishly in collaborating with an American citizen. Ehud Barak, the former prime minister of Israel, claims he advised Eitan to stop his operation.

Pollard’s wife, Anne, was privy to his betrayal, though some Israeli officials naively thought she was clueless.

By all accounts, Pollard’s self-confidence led to his downfall. A co-worker, having watched him remove documents from his office, reported the incident. From then on, Pollard was under surveillance and his apartment was throughly searched by FBI agents, two of whom are interviewed.

Pollard could have escaped to Israel, but he assumed he would not be arrested. When he finally realized his days as a spy were numbered, he and Anne drove to the Israeli embassy to seek asylum, but the security officer turned them away. Shockingly enough, Israel had no contingency plan to whisk them out of the country.

The FBI arrested the couple in November 1985, whereupon Sella fled to Israel. Rabin, the then defence minister, happened to be in Washington when all hell broke loose. Amid the uproar, he, too, flew back to Israel in a panic.

Israel’s prime minister, Shimon Peres, told U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz that he knew nothing about Pollard, but promised to return documents he had handed over to Israel.

Abraham Sofaer, the State Department’s legal advisor, was dispatched to Israel to retrieve documents and sort out the mess. In his opinion, Israel was less than forthright in its dealings with the United States. “The people involved were like crooks,” he says in a reference to the Israelis he talked to while in Israel. As for Pollard, Sofaer dismisses him as a “stupid fool.”

Having concluded that Israel had abandoned him to his fate, Pollard began talking, thinking that his impending prison sentence would not exceed seven years. U.S. Secretary of Defence Caspar Weinberger, his boss, was incensed. Convinced that Pollard had damaged U.S. security interests, he decided to make an example of him.

Pollard was given a life sentence. His wife, an accomplice, was sentenced to five years in prison. Olson believes that Pollard’s harsh treatment may have been due, in part, to antisemitism.

During the mid-1990s, President Bill Clinton considered giving Pollard a pardon, but the idea was scuppered by George Tenet, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Similar attempts by Israel to free Pollard also failed, at least until the presidency of Donald Trump.

Nearly four years after his arrival in Israel, Pollard now lives in Jerusalem, his wife having died in 2021. In the eyes of some Israelis, especially those on the right, Pollard is a hero. But to many Americans, he is a man who betrayed his country.