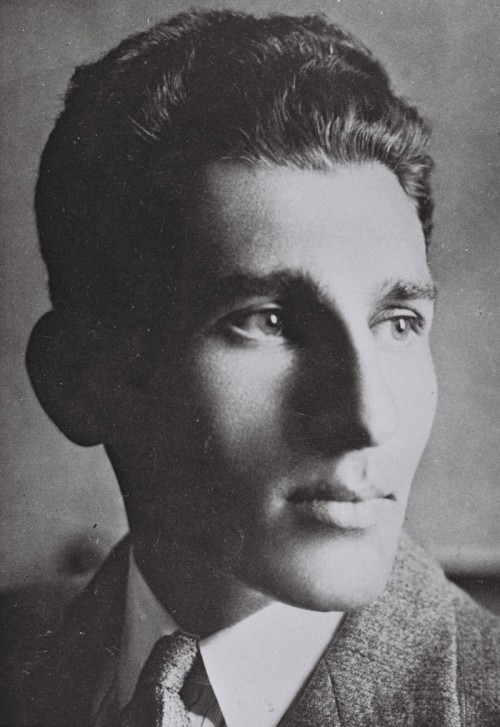

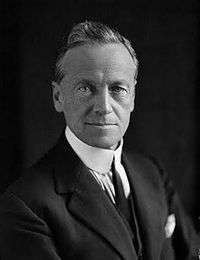

On Feb. 12, 1942, the assistant superintendent of the Palestine Police Force in Tel Aviv, Geoffrey Morton, burst into a small flat on Mizrachi Bet Street and cornered Avraham (Yair) Stern, a Polish-born fugitive whose militant Zionist group had launched a war of liberation against British colonial rule in Palestine. Within minutes, if not seconds, Stern, the 35-year-old leader of the Irgun Zvai Leumi B’Yisrael, otherwise known as the Stern Gang, lay dead in a pool of blood.

An extremist, Stern was so intent on creating a Jewish state in the face of British opposition that he went as far as proposing an alliance with Nazi Germany to counter Britain in World War II.

Although his untimely passing was mourned by only a few, Stern — one of the most quixotic figures in the annals of Zionism — is considered a hero in far-right circles in Israel today. A postage stamp bearing his image was issued and a town in central Israel, Kochav Yair, was named in his honor. (Israel’s former prime minister, Ehud Barak, lived in Kochav Yair for a while).

Patrick Bishop, a British journalist who reported from Jerusalem for the Daily Telegraph from 1989 to 1991, has written a comprehensive account of Stern and of the dogged British detective who tracked him down and killed him. The Reckoning: How the Killing of One Man Changed the Fate of the Promised Land (William Collins) is a first-rate work by a fine researcher and writer.

A romantic poet and a scholar of Hebrew literature and the classics, Stern was born in 1907 in Suwalki, 150 miles northeast of Warsaw. A member of the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair youth movement, he was sent off to Palestine by his parents in 1926 to complete his education. A year later, he enrolled in the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

As Bishop points out, his main interests were artistic, at least until the Arab riots of August 1929 that claimed the lives of scores of Jews. Chastened by these events, Stern joined the Haganah, a para-military Zionist organization that had been formed with the tacit approval of the British Mandate authorities following the Arab-Jewish disturbances of 1920.

In 1931, right-wing Zionists broke away from the Haganah and created the Irgun Zvai Leumi. A passionate debate on strategy in 1937 split the Irgun down the middle, prompting half of its members to return to the Haganah and the rest to stay put. The hardliners, acolytes of Zionist Revisionist Zeev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky, opposed the Yishuv’s policy of havlagah, favored by David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann, two of the leading Zionist luminaries in Palestine.

Proponents of havlagah believed that Zionists should cooperate with the British to achieve the Zionist dream of statehood and practise restraint in the face of Palestinian Arab provocations and attacks.

At around the time the Zionist movement was splintering into irreconcilable factions, Stern’s political views were still hazy. They were colored by his fervid poetic imagination and influenced by, among others, Elazar Ben Yair, a Jewish zealot who committed suicide in Masada in 74 AD as Roman legions besieged the mountain-top fortress; Giuseppe Garibaldi, who with a band of fighters established modern Italy, and Jozef Pilsudski, who in 1918 resurrected Poland after 123 years of foreign domination.

“Stern’s fascination with bloodshed and death led him naturally towards the Revisionist branch of Zionism,” writes Bishop, who adopts an even-handed stance toward his subject. The Revisionist message was unambiguous: If Jews wanted a state, they would have to fight for it by force of arms. There was no other way.

Stern was recruited in 1932 by a fellow Hebrew University student, David Raziel, who would be the Irgun’s Jerusalem commander. Stern co-edited the Irgun magazine, which preached unyielding resistance to Arab demands. In 1933, he left to continue his studies in Italy, but was recalled in 1934 to be the Irgun’s purchaser of arms in Italy and Poland. For the next few years, he divided his time between Palestine and Europe.

Stern was closely involved in a plan, formulated by Jabotinsky, to train a cadre of 40,000 Polish Jews who would form the core of a Jewish army to wrest Palestine from the Arabs and challenge British supremacy in Palestine. The Polish government, eager to encourage Jewish emigration, was a willing collaborator.

Although Stern was an admirer of Jabotinsky, the pair had a falling-out. Jabotinsky was of the view that a future Jewish state could be on good terms with Britain, but as far as Stern was concerned, the British were the arch enemy, blocking the road to Jewish statehood, particularly after the publication of the 1939 White Paper on the future of Palestine.

After the outbreak of World War II, Stern and Raziel had a sharp disagreement over tactics. Raziel, the firebrand, now endorsed Jabotinsky’s pragmatic edict that the Irgun should cooperate with the British rather than fight them. Stern disagreed, saying that the Irgun should take its hostility to Britain to its logical conclusion.

“Instead of joining forces with the (British) empire, as Raziel argued, they should team up with its enemies,” Bishop writes. “It was true that Nazi Germany embodied antisemitism, but the Polish government had been antisemitic and he had successfully done business with it. Why not try the same approach with the Axis powers and forge a deal where they would send the Irgun their unwanted Jews and the Irgun would fight on their behalf in Palestine?”

Germany’s military successes in Europe and Italy’s advances in North Africa strengthened Stern’s belief that Britain was heading toward defeat and that the interests of Jews were best served by dealing with Berlin and Rome.

With the vast majority of Revisionists having parted ways with Stern on this contentious issue, he broke away from the Irgun. In July 1940, he announced the formation of the Irgun Zvai Leumi B’Yisrael, taking about 100 diehards with him. Shortly afterward, his followers robbed a bank, making off with a huge haul. In Bishop’s opinion, the robbery was a turning point, enabling Stern to pay fighters, fund further operations, buy weapons and even finance a clandestine newspaper.

As Bishop suggests, Stern was now seen as a threat to Britain’s war effort, all the more so after his envoys contacted the Germans.

With overtures to Italy having apparently reached a dead end, a footnote Bishop describes in a few pages, Stern turned his attention to Germany, whom he regarded as the real masters of Europe.

Stern sent Naftali Lubentchik, who was in charge of the group’s finances, to Beirut to contact a visiting German diplomat, Werner Otto von Hentig, who headed the foreign ministry’s Middle East bureau and had been dispatched to Lebanon and Syria on a fact-finding mission.

“In exchange for participation in the war against the British, he proposed that the Reich help his organization establish a Jewish state in Eretz Yisrael and allow the Jews from the (German) occupied lands to make aliyah and settle in it,” writes Bishop.

Von Hentig passed on the memorandum to the foreign ministry in Berlin. When he returned to Germany, he asked its deputy director, Ernst von Weizsacker, whether he had seen the document. Bishop elaborates: “Von Weizsacker sharpened his gaze. ‘Do you really think the Reich would be interested in a Jewish state in Palestine when we are trying to win over the Arabs and Muslims to further our war aims?'” he asked archly.'”

Stern was incredibly foolish and naive to assume that an entente with Nazi Germany was possible. Yet, as Bishop observes, he stubbornly clung to his belief, “spinning fantasies of how collaboration might work.”

In the meantime, he shifted his focus to the Palestine Police Force, which had launched a manhunt for Stern and his compatriots. Stern set his sights on Morton — who since 1939 had commanded the Tel Aviv Criminal Investigation Department, tasked with countering Jewish and Arab political violence — and his Hebrew-speaking colleague, Tom Wilkin. After assassinating the highest-ranking Jewish member of the Palestine Police Force, Solomon Schiff, the Stern Gang targeted Morton, but failed to kill him. However, they managed to murder Wilkin.

In the wake of Stern’s death, his followers regrouped, renaming Irgun Zvai Leumi B’Yisrael. Henceforth, it would be called Lohamei Herut Israel, or Lehi. Its leaders were Yitzhak Shamir (a future Israeli prime minister), Nathan Yellin-Mor and Israel Eldad. They joined forces with the Irgun, whose new military commander, Menachem Begin, would be Israel’s prime minister from 1977 to 1983.

As allied armies fought Italy and Germany in North African battlefields, a Lehi assassination squad tried, unsuccessfully, to murder Sir Harold MacMichael, the British high commissioner in Palestine. In November 1944, Lehi assassins killed Lord Moyne, the British minister of state in the Middle East, in Cairo.

Moyne’s death caused a wave of revulsion in Palestine and prompted the Zionist leadership to cooperate with the British in the attempt to eradicate the Irgun and Lehi. This partnership of convenience ended in the summer of 1945, following the landslide victory of the Labor Party in Britain. Traditionally, the Labor Party had been friendly to Zionist aspirations. But the new British foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin, upended this policy, with the result that all Zionist factions put aside their differences and fought in unison against Britain.

By then, Morton had left Palestine, having been successively reassigned to the Caribbean island of Trinidad and Nyasaland, a landlocked British colony in southeast Africa.

For the rest of his life, Bishop says, he was haunted by his role in the Stern affair. As he puts it, ” He would never be able to shake off the consequences of the reckoning in the flat in Mizrachi Bet Street.”

In his memoirs, The Revolt, published in Britain in 1951, Begin accused Morton and his fellow detectives of having murdered the “unarmed” Stern. Morton sued Begin and won a substantial sum in damages. It would be the first of four libel suits faced by Morton over the matter.

To this day, it isn’t entirely clear whether Morton and his colleagues shot an unarmed man in cold blood. Bernard Stamp, a British detective who supposedly witnessed the shooting, claims that Stern was “doomed” from the moment he was found. Confronted with Stamp’s testimony, Morton claimed that Stamp was not “in the room at the time of the shooting.”

Morton died in 1996, taking his secrets to the grave. We may never know the full truth about that violent encounter in Tel Aviv in 1942 in which Stern was killed, but it sure makes a good story.