Erez Laufer’s biopic, Rabin In His Own Words, humanizes the late Israeli prime minister.

Rabin, shy and reserved, invariably projected coolness and aloofness in public appearances. But in this film, scheduled to be screened at the Canadian International Documentary Festival in Toronto on May 2, May 3 and May 6, Rabin comes off as a person who could project warmth.

In the first few minutes of this absorbing documentary, based on interviews and archival news clips, he fully admits he’s not “expressive.” But soon enough, we catch glimpses of a man who could be swayed by emotion.

Rabin was a son who adored his parents, a husband who was in love with his wife, a father who tried to spend quality time with his children, and a prime minister who awkwardly asked the American First Lady for a dance at a White House ball and who chivalrously defended his wife when a political scandal forced him out of office.

Lauder underscores these facets of his personality, but in the main, he presents a familiar portrait of Rabin — the general who led Israel to victory in the Six Day War and the leader who attempted to come to terms with the Palestinians through the Oslo process and who signed a peace treaty with neighboring Jordan.

The film unfolds in chronological order, from Rabin’s birth in 1922 in British Mandate Palestine to his assassination in Tel Aviv on November 4, 1994.

The scion of working-class Russian Jews who lived spartan lives, Rabin had early aspirations of becoming a farmer on a kibbutz. He studied at an agricultural school and set his sights on studying water engineering, but his life was forever changed by the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Laufer summarizes his war service in cursory fashion, even neglecting to mention Rabin’s role as a brigade commander in the expulsion of Palestinian Arabs from the towns of Lod and Ramle.

As Rabin tells an interviewer, he decided to become a professional soldier after several of his men, all under the age of 18, were killed. Their untimely deaths left a scar on his psyche.

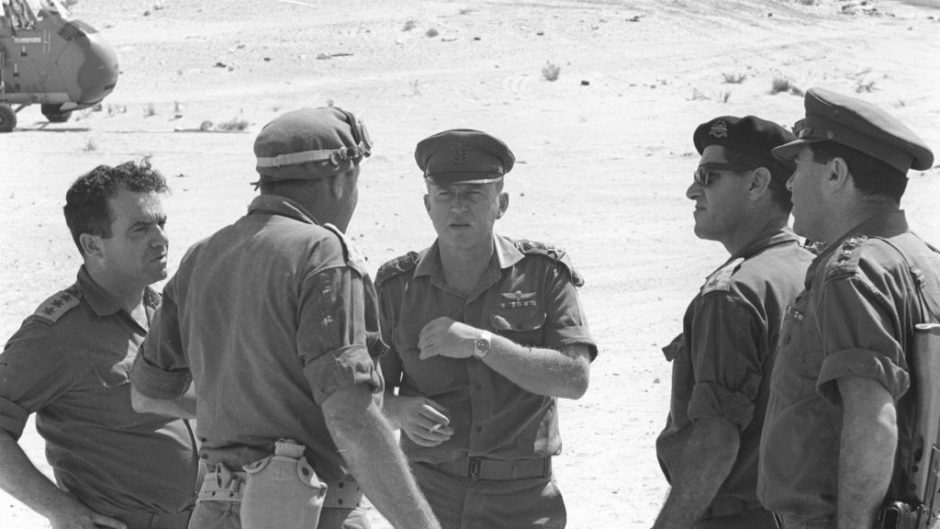

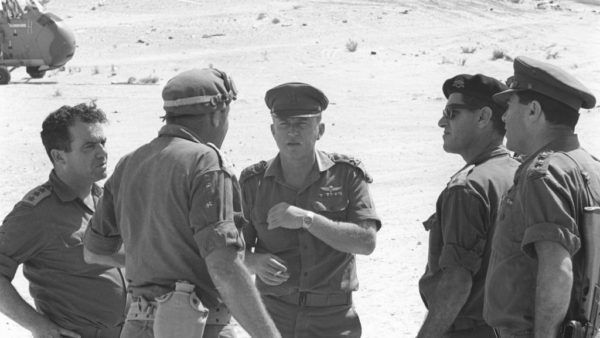

Laufer rushes us through his rise in the ranks from Northern front commander in 1956 to chief of staff in 1964. He spends considerably more time on the increasingly tense period leading up Six Day War.

With Arab armies massing on Israel’s borders, Rabin grew melancholy and depressed, a condition that appears to have been aggravated by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister. In a moment of searing candour, Ben-Gurion advised Rabin to avoid war at all costs, a piece of advice that may have precipitated his nervous breakdown.

On the eve of the war, Rabin took a day off to calm his nerves. Refreshed, he returned to his duties and led Israel into battle. With Israel having defeated its enemies, Rabin was feted as a hero.

Israel’s prime minister, Levi Eshkol, was flabbergasted when Rabin asked for an ambassadorship. For the next five years, he was Israel’s envoy in Washington, D.C., but Laufer tells us precious little about Rabin’s tenure as ambassador to the United States. In passing, Rabin is quoted as saying that Moshe Dayan, the defence minister, was a “national disaster.” Too bad he doesn’t elaborate.

Untainted by Israel’s mistakes in the Yom Kippur War, Rabin succeeded Golda Meir as prime minister. One of the issues that commanded his attention was the network of outposts/settlements that religious and secular nationalist Jews had unilaterally built in the West Bank after the Six Day War under the guidance of Gush Emunim, an organization animated by messianic nationalism.

In scathing comments, Rabin describes Gush Emunim as a “cancer” in Israel’s body politic that would bring disaster upon the Jewish state. He claims that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank would transform Israel into an “apartheid” state.

Rabin suffered a fall from grace after news leaked out that his wife, Leah, had illegal bank accounts in the United States. Forced to step aside, he was succeeded by his rival, Shimon Peres. Laufer glosses over Rabin’s job as defence minister in the post-1984 national unity government.

Laufer portrays Rabin as a man of peace who sought coexistence with the Palestinians. He got his chance to make good on his vision in 1992, when he became prime minister again. In a leap of faith, Rabin authorized secret negotiations with the PLO that culminated in the 1993 Oslo accord.

Rabin dismissed right-wing critics who lambasted his rapprochement with the Palestinians, hewing to this policy even after deadly suicide bombings disillusioned many Israelis. He insisted that peace was necessary for Israel’s survival as a Jewish state, a position that Israel’s current prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, sharply rejects.