Since the collapse of communism in Poland more than three decades ago, Poles have been engaged in a passionate debate over what kind of a country it is and should be.

Traditionalists believe that Polish identity is inextricably bound up with the Catholic Church and conservative values emphasizing Polish martyrdom. Liberals promote secularism, civic nationalism and progressive ideas, and question some of the main tenets of Polish mythology.

History and memory are integral components of this ongoing national conversation. Within this context is the hotly debated issue of Polish-Jewish relations.

As the historian Genevieve Zubrzycki writes in her penetrating and persuasive book, Resurrecting the Jew: Nationalism, Philosemitism, And Poland’s Jewish Revival (Princeton University Press), one of the incendiary topics that divides Poles in this divisive debate turns on the participation of ethnic Poles in violent crimes against Polish Jews before, during and after World War II.

Right-wingers have described this reckoning as anti-Polish defamation, as she points out, but their opponents have welcomed this process of soul-searching at a moment when Poland’s small Jewish community, a pale imitation of its pre-war self, is undergoing a significant renewal.

She contends that this debate is part of a larger philosophical and historical struggle to define the essence of Polishness. While conservatives associate Polishness with Catholicism and underscore the role of Poles in the rescue of Jews during the Holocaust, liberals challenge this narrow approach and strive to advance a civic and secular definition of Polish national identity.

The Polish American historian Jan Tomasz Gross ignited a storm in 2000 with the publication of Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, a hard-hitting book that implicated Poles in the murder of Jews in 1941. The Polish parliament entered the fray in 2018 when it passed an amendment to a law threatening imprisonment to anyone who claims that the “Polish nation” or the Republic of Poland was responsible for crimes committed by the Nazis during Germany’s occupation of Poland from 1939 to 1945.

This debate has unfolded as numerous Polish Catholics have evinced an interest, if not a passion, in all things Jewish, says Zubrzycki, a professor of sociology at the University of Michigan and the author of The Crosses of Auschwitz: Nationalism and Religion in Post-Communist Poland, which examined the relationship between Polishness and Catholicism after 1989.

A Catholic born and raised in a francophone family in Quebec, Zubrzycki identifies as a Qubecoise. Her mother is a French Canadian, but her father, the son of Polish refugees, was born in France. In her late teens, she visited Poland for the first time. During the 1990s, she lived there for several years, witnessing the growing interest of Poles in the legacy of Polish Jews. From the summer of 2010 until the autumn of 2019, she conducted thirty weeks of fieldwork in Poland.

This Polish fascination with Jews is all-encompassing.

It expresses itself in the proliferation of Judaica book shops, Jewish-style restaurants and cafes and in the staging of annual Jewish cultural festivals in more than a dozen cities and towns. It is also evident in the construction of museums and memorials, the development of Jewish and Holocaust studies programs in universities, the publication of hundreds of books and monographs on Jewish subjects, the popularity of klezmer music, and the modest but steady number of conversions to Judaism.

In her estimation, the revival is predominantly driven by non-Jews. “What motivates their efforts? One key motivation is to recover what has been lost and erased so as to recreate Poland’s multicultural past and thereby build and promote a pluralistic secular society in and against an ethnically and religiously homogeneous nation-state.”

As she reminds a reader, Poland has been ethnically and religiously diverse for most of its existence. In 1939, on the eve of Germany’s invasion, Poles accounted for two-thirds of Poland’s population, with the rest of its citizens being ethnic Germans, Ukrainians and 3.3 million Jews. By the late 1940s, the demographics had radically changed, with 95 percent of the population being ethnic Poles. Present-day Poland is similarly homogeneous from an ethnic point of view.

“Although the diversity that characterized Poland for most of its history is unlikely to return, progressive nationalists see the recognition of this legacy as a platform from which to build a more open society,” she writes. “They seek to push Poland toward an internationally normative model of nationhood, one that values and encourages pluralism and multiculturalism.”

Poland’s Jewish past, and present, hold the key to this imagined cosmopolitan future, she adds.

At present, 4,500 to 13,000 Jews live in Poland, the wide variation being a function of how Jewish ancestry is defined. By another estimate, 40,000 to 100,000 Poles are of partial Jewish descent. “Whatever the number, double it and then add one,” the chief rabbi of Poland, Michael Schudrich, told Zubrzycki. “Because there’s always one coming out of the closet.”

For some Polish Jews who lived through the Holocaust, the concealment of their real identity was a matter of life and death. After the war, fears of violence, discrimination and social stigma prompted such Jews to retain their assumed Christian identities. Still other Jews who had spent the war years in the Soviet Union and returned to Poland after Germany’s defeat were communists or socialists and hewed to a vision of a secular and post-ethnic society. Many of their children were either unaware of their Jewish background or were raised in families indifferent to Judaism and Jewish traditions.

Nonetheless, as Zubrzycki notes, there has been a slow but steady growth of the Jewish community and the expansion of Jewish community centers since the fall of communism.

“Supporting the revival of Jewish culture and the renewal of Jewish community life in Poland can therefore be an explicit attempt by nominal Catholics to undermine the power of the Catholic Church and oppose the monopoly of the Catholic Right over the definition of Polishness,” she says. “For other religious minorities, too, the Jewish revival provides a counterweight to the heavy presence of Catholicism in Poland.”

Several Poles she interviewed claimed that the revival of Jewish culture would allow Poles to become “authentically” multicultural and bring Poland back to its “true essence” as a multinational nation.

For Poland’s current conservative government, which is controlled by the right-wing Law and Justice Party, “Jewishness is now seen as key to polishing Poland’s image in international venues,” Zubrzycki goes on to say.

During the communist era, material traces of Poland’s Jewish past were largely eliminated. Jewish communal buildings, notably synagogues and yeshivas, were either demolished or repurposed as cinemas, libraries or cultural centers. Cemeteries were abandoned and neglected. “The very memory of Polish Jewish history was slowly but surely buried,” she says.

For the past two decades, however, “memory activists” have worked to resurrect this history and awaken Poles’ memories of Jews. “For them, the loss of Jewish memory is a wound in the nation’s body. Jewish absence has come to represent the loss of a multicultural Poland — of what was, and what could have been.”

She cites examples.

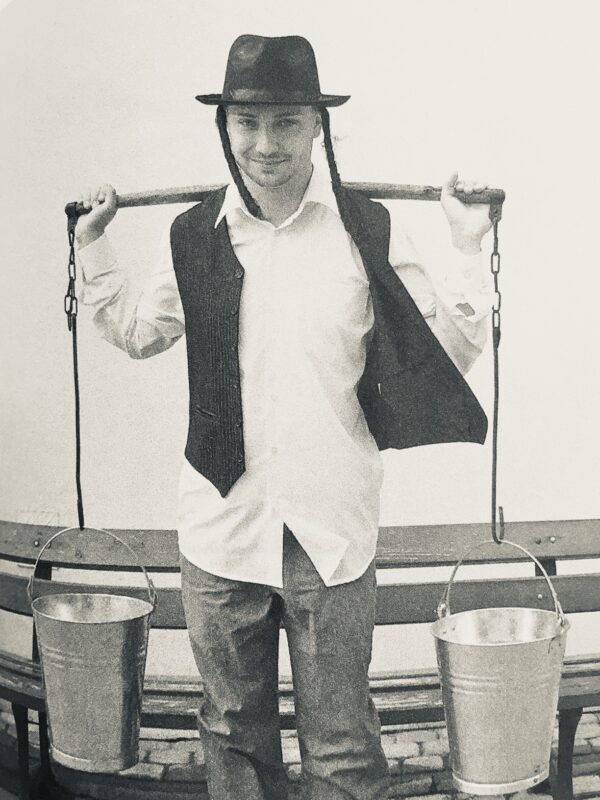

During the 1990s, the former Jewish quarter in Krakow, Kazimierz, underwent a process of gentrification. Now revitalized, this neighborhood bristles with hotels, cafes, restaurants, book stores and souvenir shops, some of which sell wooden figurines dressed as ultra-Orthodox Jews clutching coins. They are sold as good luck charms, but Jews think they perpetuate antisemitic stereotypes and tropes.

Founded in 1988 as a two-day local event, the Jewish Culture Festival in Krakow has contributed to the revival of Kazimierz and has since become a “core institution in the dissemination of Jewish culture in Poland” and an internationally-recognized 10-day extravaganza with a gargantuan program.

In the eastern city of Lublin, the Grodzka Gate Theatre organizes educational workshops on the history of the region’s Jewish heritage.

Marek Edelman, the last surviving leader of the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising, commemorated the revolt annually on April 19 with a bouquet of yellow daffodils.

After his death in 2009, his friends and members of the Jewish community followed his lead. Since then, schools in small towns and villages throughout Poland have made and distributed daffodils in April. Zubrzycki regards it as an “act of solidarity and resistance to the distinction made by Nazis (and by many Poles) between Jews and non-Jews.”

Commemorative walking paths tracing the vanished walls of the former Nazi ghetto in Warsaw have been laid down. In another project, a street artist has shown the location of the wooden footbridge over Chlodna Street that linked the small and large ghettos.

More than a dozen Jewish history museums have opened in the last 20 years, including Krakow’s Galicia Jewish Museum and the Oskar Schindler Enamel Factory Museum.

The Polin Museum in Warsaw’s Muranow’s district, which was inaugurated in 2014 and faces Nathan Rapoport’s Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, is the crown jewel of Jewish museums in Poland.

“The core exhibition emphasizes that Poland is not just a graveyard of European Jewry but also the place where it flourished in rich and diverse ecologies,” writes Zubrzycki. In addition, the museum undermines “the dominant mythology of Poland’s intrinsic religious and ethno-national homogeneity. By emphasizing that Poland was the place where Jews dwelled for a thousand years, the museum highlights that the current demographic makeup of Poland is the exception rather than the rule in Polish history.”

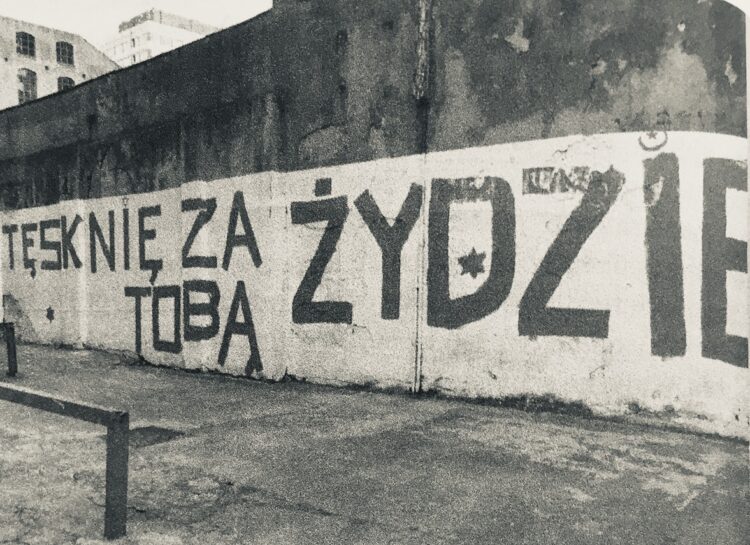

In 2009, a Pole named Rafal Betlejewski painted the words “I miss you, Jew” under a bridge in Warsaw. His gesture turned into a collective memorial project aimed at recovering the “true” Poland that was lost with the annihilation of 90 percent of Polish Jewry during the Holocaust and the flight of some 15,000 Jews in the wake of the 1968 antisemitic purges.

Christian evangelicals have celebrated Passover with seder plates, matzoh and kosher wine, in what Zubrzycki calls a case of “cultural appropriation.”

Still other Poles listen to Jewish music, eat in Jewish restaurants, drink kosher vodka, learn Jewish dances, enrol in Jewish studies programs at universities, clean up Jewish cemeteries, and provide services to Jewish seniors. A small proportion consider conversion to Judaism.

During her discussions with Poles who have been drawn to Poland’s Jewish dimension, one interviewee said, “We could talk about (Jewish culture) as a foreign culture, different from Polish culture, but we are still aware that we’re talking about a culture that existed for centuries. But it’s still something exotic, right? And yet, totally close to us. So it’s easy to become interested in (Jews and Jewish culture) and become fascinated. It becomes fashionable.”

Jewishness in Poland is therefore both “other” and “ours,” Zubrzycki concludes. “Julian Tuwim, Bruno Schulz and Janusz Korczak are consistently invoked in discussions on the contribution of Polish Jews to Polish literature … Embracing pluralism and Jewishness not only helps brand Poland as modern and European; it also gives Poland back to its ‘true’ shape.”

Zubrzycki argues that the recognition of the Jewish past enables public figures, teachers and social and political activists to call for a civic, rather than an ethnic or religious, definition of Polishness.

In closing, she warns that Polish philosemitism poses a risk for Jews. As she puts it, “The resurrection of Jewish culture is primarily made by Poles, for Poles, and in the name of Polish culture. Jews are included in the national narrative and into an expanded conception of the national self precisely because they are considered to be different, Poland’s internal ‘Other.’

“Paradoxically, the liberal inclusion of Jews within the symbolic boundaries of the nation, in order to expand notions of Polishness, entails the continued Othering of Jews. In order for a multicultural, diverse Poland to exist, the Jew must remain immediately Other. For Poland to become plural and inclusive, distinctions between citizens based on ethnicity and religion are highlighted, legitimized and even celebrated.”

This is the complex paradox she leaves readers to ponder in her erudite and engaging book.