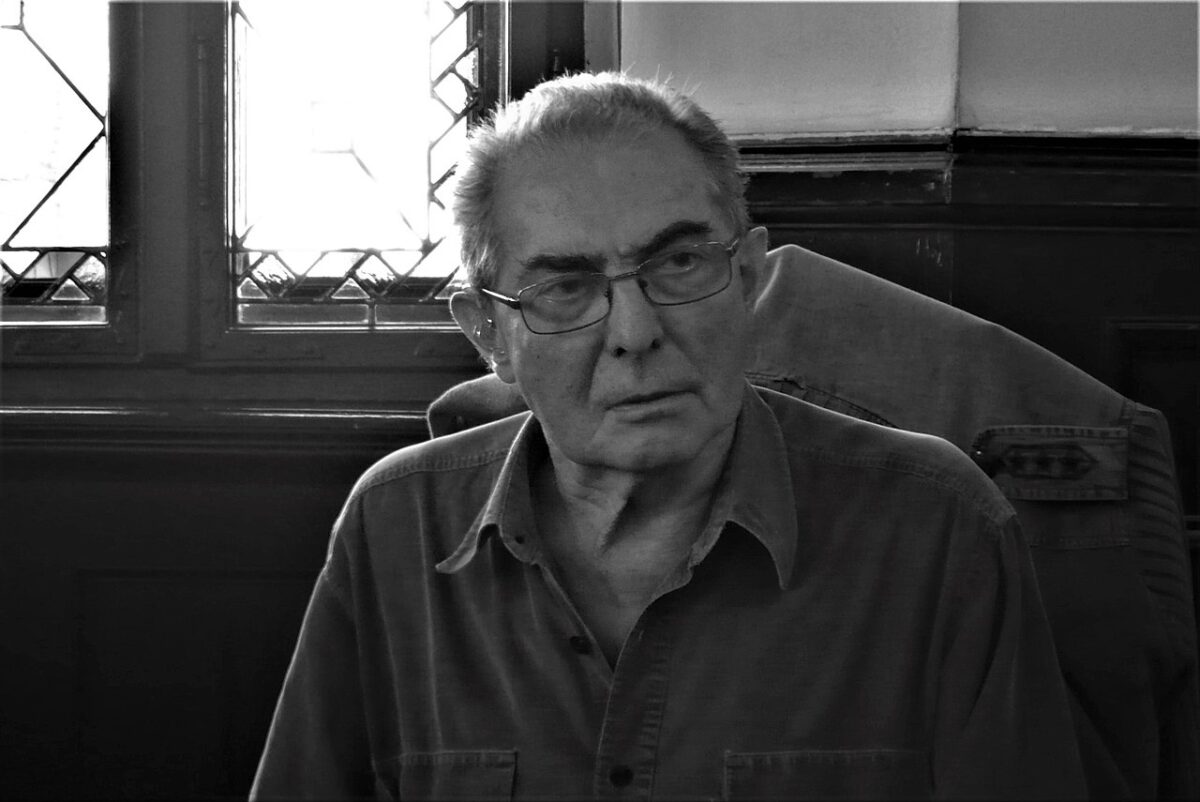

Karol Modzelewski was an iconoclast writ large, one of Poland’s leading dissidents during the communist era.

A dyed-in-the-wool contrarian, he was Jewish by birth, yet identified as a Pole. He belonged to the Communist Party, yet openly criticized it.

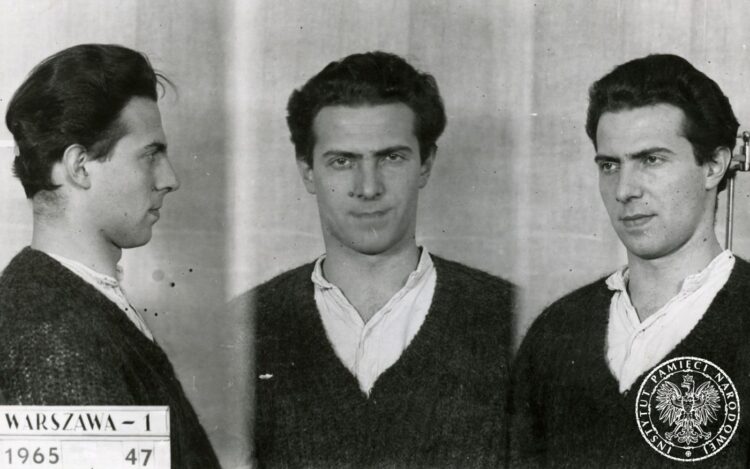

His fearlessness cost him dearly. During the 1960s and 1980s, he languished in prison for a total of eight-and-a-half years.

A historian by profession, he was a founder and spokesman of the Solidarity political movement, to which he gave its name. In post-communist Poland, his egalitarian leftist sensibility put him out of step with the new, pro-capitalist government. Nonetheless, he was elected to the Senate and was a professor of medieval studies at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw.

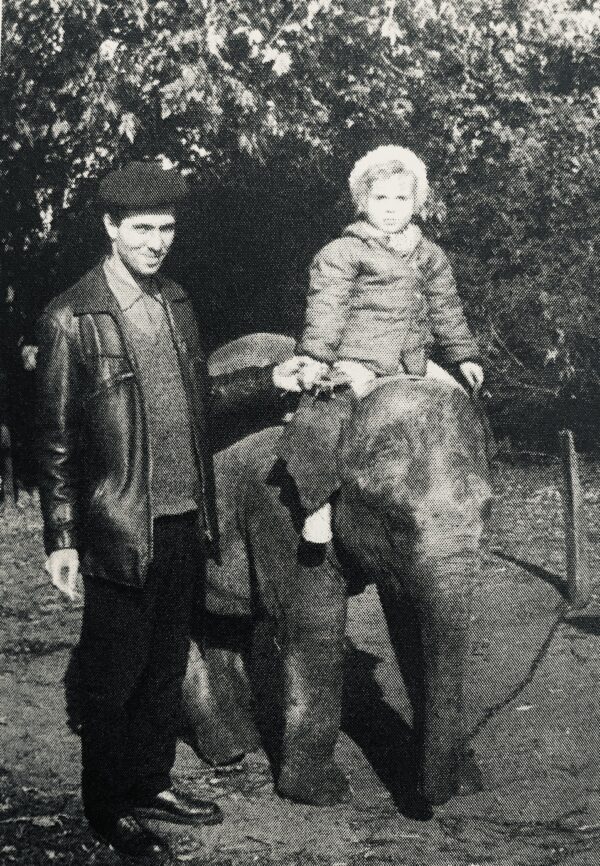

Modzelewski died in 2019 at the age of 82. Before his death, he finished his memoirs. Originally published in Polish in 2013, the book has been translated into English by Frank L. Vigoda under the title of Riding History to Death: Confessions of a Battered Rider (Rowman & Littlefield).

It begins with a useful introduction by Irene Grudzinska Gross, a Polish American historian who provides a sweeping overview.

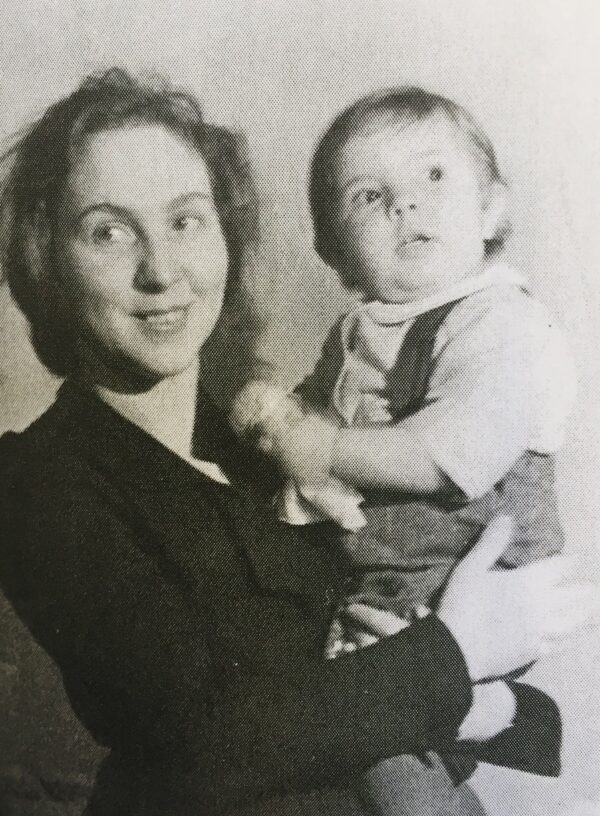

Born in Moscow in 1937, he was originally known as Kiril Budniewicz. His Russian Jewish biological father, Aleksander, spent years in a Soviet gulag.

His Lithuanian Jewish mother, Natalia Wilter, was an academic who specialized in Russian and Polish literature. Natalia, having divorced Budniewicz, remarried. Her new husband, Zygmunt Modzelewski, was a Polish communist who had just been released from a Soviet jail. He adopted Kiril, and in 1945, they all moved to Poland.

Modzelewski embraced his new identity with a passion. “His sense of being a Pole was strong and unwavering,” says Grudzinska Gross. Such was his allegiance to Poland that he dismissed as “relatively unimportant” the antisemitic campaign launched by the Polish regime following the Six Day War in 1967. He considered the purge of Jews an act of “sectarian politics.”

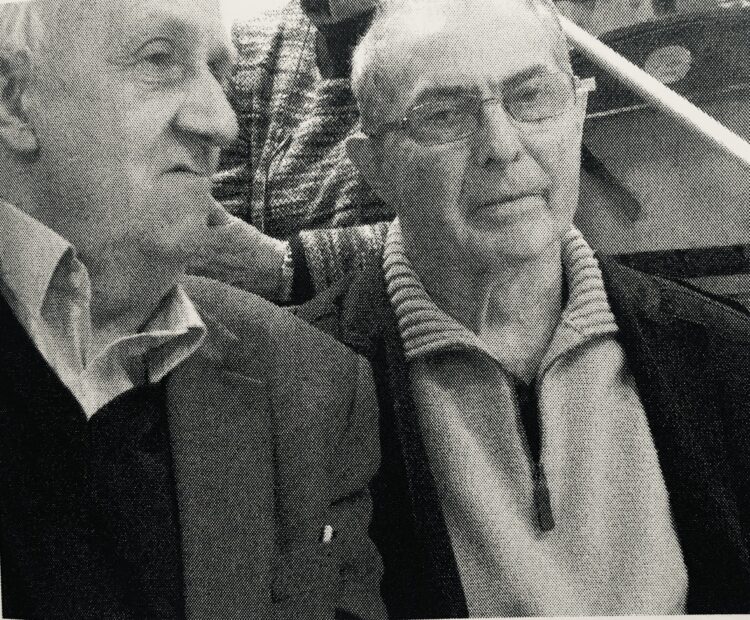

During the 1950s, he studied medieval history and Italian in Italy. In the mid-1960s, he and his friend, Jacek Kuron, published an open letter to the Polish United Workers Party lambasting the government from a leftist perspective. Rather than being ruled by the working class, Poland was governed by the Communist Party elite, complained Modzelewski, a Marxist. The critique landed him and Kuron in prison in 1965. Being a serial dissenter, Modzelewski would be sent back to jail in 1968 and again in 1982.

Modzelewski played a key role in the formation of Solidarity, which was instrumental in the downfall of communism. But he found himself at odds with it when it became hierarchical.

During the final years of his life, he devoted himself to his career as a scholar and to his position as a deputy president of the Polish Academy of Science.

In his memoirs, he describes Zygmunt Modzelewski as his “true father because he raised me, and, I believe, he influenced me deeply.” As he observes, “I am a second-generation revolutionary. My father was a true communist. He worked for the sake of the proletariat revolution in which he deeply believed.”

Born in Czestochowa in 1900, he was the son of a railroad worker. Prior to World War II, he studied law at Jagiellonian University in Krakow. For a brief period after the war, he was foreign minister. He remained in the nomenklatura as a member of the Council of State.

By the austere standards of the day, they lived sumptuously in a five-bedroom apartment and then in a villa with a garden. They were attended to by a handyman, a housekeeper and a driver, enjoyed vacations in mountain resorts like Zakopane, and shopped in special bountifully-stocked food stores closed to the public.

Modzelewski devotes several pages to his Jewish background.

He admits he was deeply offended when the son of a clerk in the Polish embassy in Moscow insisted that he, Modzelewski, was a Jew rather than a Russian. Yet he also minimizes its impact. “Perhaps (he) did not mean anything bad, perhaps he himself was a son of a Polish communist with Jewish roots and was trying to let me know that I was like him.”

After acknowledging that Poland is perceived as “an antisemitic country,” he hastens to add that he has rarely been “reproached” for his Jewish ancestry. Citing the state-sponsored anti-Zionist campaign of 1967 and 1968, he goes on to say that his antisemitic tormentors usually have been “people serving the authorities.”

Contending he has been treated decently in Poland, he writes, “Sometimes my friends, sometimes my acquaintances, and sometimes strangers will grab me gently by the arm, look me in the eyes, and let me know — you are one of us, and we invite you to join our community.”

He claims he did not accept their invitation, even though he regards himself as a Polish patriot. “I really like you … and I feel good among you, but I will not join the circle of ethnic initiation. The sense of national identity is not inscribed in the genes but in the head.”

Needless to say, he opposed Jewish particularism: “The walls that separated the Jewish community from all other communities was erected on both sides, and they grew. Finally they took the shape of segregation applied to every aspect of life.”

Elaborating on this theme, he says, “I do not subscribe to the view that barricading themselves inside religious tradition and isolating themselves socially and culturally within ghettos were the Jew’s heroic self-defence against losing national identity after having lost their ancient homeland. In my opinion, the belief in the uniqueness of the Jews among the nations does not befit a historian.”

Turning to the events of 1968, he suggests that Communist Party leader Wladyslaw Gomulka initiated the anti-Zionist campaign and that his rival, Interior Minister Mieczyslaw Moczar, cynically exploited the situation in a power struggle for dominance. “Over several months there was a purge in party and state personnel under the banner of an antisemitic campaign,” he says.

He discloses that the secret police checked the “Aryan background” of many Polish citizens during this period, as if the Nazi governor of occupied Poland, Hans Frank, still resided in Krakow’s Wawel Castle.

“There were many thoughtful and courageous people who did not let themselves be fooled or threatened,” he writes of this noxious time. “But there were also many who more or less gave in to the propaganda.”

In an analysis of Polish-style communism, Modzelewski tries to strike a balance. “Even if communist Poland never matched the ideal, it significantly flattened incomes and increased social mobility. It gave longtime disadvantaged segments of society a prospect for advancement.”

During the best times, he explains, ordinary Poles could expect full employment, extensive social benefits, cheap housing, free health services and education.

After 1956, he points out, Poland was unique in the communist bloc of nations for its “liberalism” toward artists and scholars. But after returning from his studies in Italy, he profoundly felt “the humiliating contrast between the everyday life of a free country and life in Poland.”

Modzelewski offers a few observations about Solidarity leader Lech Walesa. He was a simple man whose “way of thinking and acting in many ways had more to do with traditional peasant culture than with the intelligentsia’s vision of working-class consciousness.”

Yet he had an exceptional gift for communicating with crowds. “More than once, Walesa completely changed the meaning of a sentence before he had finished, when he realized that the mood of the listeners required it.”

Walesa was “excellent” in his role of leader of the struggle for freedom, but after assuming the Polish presidency, “he wanted to become a strongman and tried to hold the instruments of enforcement in his hands.”

He admits he did not imagine he would live to see “an independent Poland.” But he tempers this admission with a barbed comment: “The beautiful face of free Poland has some ugly blemishes that have been carried on from our past — a past that is farther away, as well as recent …”

Modzelewski’s memoirs, though generally interesting, ramble and meander far too often. And his prose style tends to be turgid. Yet Riding History to Death provides a reader with keen insights into postwar Poland.