Barbara Perry and Ryan Scrivens contend that there have been too few attempts by academics to systematically analyze the ideologies and activities of right-wing extremists in Canada, resulting in a paucity of books and monographs on this important topic.

“There can be little doubt, then, that a theoretically informed contemporary assessment is needed,” they believe.

Perry, a professor at the faculty of social science and humanities at the University of Ontario’s Institute of Technology, and Scrivens, an assistant professor at Michigan State University’s School of Criminal Justice, fill the gap quite deftly in Right-Wing Extremism in Canada, a scholarly volume published by Palgrave Macmillan and dedicated to all those who “challenge hatred.”

Their book implicitly challenges the rosy misconception that Canada has always been and still is a tolerant multicultural haven attuned to racial, ethnic and religious diversity. Certainly, this is the image that Canada prefers to project, and to some degree it is an accurate one.

But as the authors correctly point out early in their informative and wide-ranging work, Canada has come a long way from the days when it was a tight-assed Anglo-Saxon and French bastion of intolerance, racism and antisemitism.

During the 1920s, anti-Catholic, anti-immigration and racist sentiment was widespread in this country, judging by the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan and the activities of the Orange Order. In the decade to follow, antisemitic organizations such as the Toronto Swastika Club, the National Social Christian Party and the Canadian Union of Fascists were established and extremists like Adrien Arcand and John Ross Taylor attracted followers.

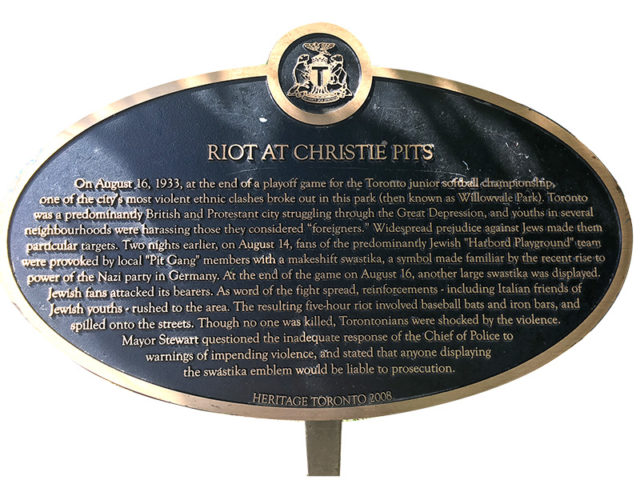

Lest we forget, the 1933 Christie Pitts riot in Toronto underscored the extent to which antisemitism flourished in Canada.

Fascists scurried into rabbit holes after Nazi Germany’s defeat in World War II, but reemerged in the 1960s. John Beattie founded the Canadian Nazi Party in 1965, while Frederick Paul Fromm, Don Andrews and Leigh Smith created the Edmund Burke Society.

From that point onward, far-right groups like the Western Guard, Heritage Front and Alternative Forum surfaced.

Perry and Scrivens classify the leaders of right-wing extremist organizations under two broad categories: ideologues and gurus. The first ones provide “the intellectual underpinnings and conceptual tools that are taken up by others.” The second ones convey the “guidance and mentorship” that young, emerging local leaders seek.”

Among the ideologues they cite are Douglas Christie, a lawyer from British Columbia who defended hatemongers ranging from James Keegstra and Ernst Zundel to Malcolm Ross and Doug Collins. Christie, who died in 2013, also represented Hungarian war criminal Imre Finta.

The first guru on their list is Fromm, whom they describe as “one of Canada’s most notorious white nationalists activists.” Fromm is currently the head of the Canadian Association for Free Expression and Citizens for Foreign Aid Reform. He has shared the stage with British Holocaust denier David Irving and organized rallies in support of Zundel, a German citizen who was deported from Canada.

In addition, Perry and Scrivens deal with “lone actors,” or individuals with no known formal ties to identifiable groups who have committed crimes.They mention, among others, Justin Christian Bourque, who was accused of murdering three RCMP officers in 2014. On his Facebook page was an antisemitic cartoon depicting the Jewish banker Jacob Rothschild with a hooked nose, huge teeth and beady eyes.

In their view, the criminality of right-wing extremists and organizations falls into three clusters: non-violent crime, criminal violence and extremist violence. In general, their targets are Muslims, Jews, people of color, Afro-Canadians, Asians and South Asians.

Striving to establish a “facade of legitimacy” within mainstream society, they have toned down their rhetoric and dispensed with white robes and brown shirts. As long ago as the 1980s, David Duke, the former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan in Louisiana, recognized that legitimacy could only be achieved through moderation and respectability.

Proceeding from that starting point, right-wing extremists entered municipal and provincial election races in Ontario in 2014. Jeff Goodall of the Edmund Burke Society was a candidate for Oshawa’s city council. Fromm ran for mayor of Mississauga. Andrews threw his hat into the ring for the mayoralty of Toronto. They all lost, having “injected a note of intolerance into political debate.”

Historically, hate groups have recruited members and disseminated their messages through traditional media or by word of mouth. But in recent years, Perry and Scrivens note, they have flocked to the digital world, using the internet and social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

White power musicians are also part of the mix, they add, citing the Canadian founder of Resistance Records, George Burdi, a resident of Ontario. Quebec, however, appears to be the center of the white power music scene in Canada.

The majority of Canadian white extremist organizations have a very short shelf life, from a few months to a year, they claim. Neo-Nazi and skinhead movements, in particular, are plagued by conflict and constant infighting, with members regularly jockeying for power and status. “This mirrors the volatility of the white power movement in the United States,” they write.

The movement is prone to fragmentation, due in part to its weak leadership. Most of its leaders are tough and charismatic, they concede. “But they are often uneducated, cannot articulate themselves, and lack a strategic capacity to maintain group cohesion. When leaders are in fact sustainable, they usually become known to the police, which in turn can weaken their position within a group.”

Perry and Scrivens contend that most police services underestimate the threat posed by these groups and do not take them seriously enough. “They trivialize their potential for growth and violence” and are much more focused on left-wing extremism or Islamist-inspired radicalism. Generally, the police regard the right-wing extremists as “losers without a cause.”

On the bright side, they credit anti-racism and anti-fascist community groups with helping police forces counter right-wing extremists.

In an epilogue, to which Perry’s colleague Tanner Mirrlees contributes, they argue that the “politics of hate” in Canada, unleashed most recently by former U.S. President Donald Trump, galvanized Canadian white supremacists and neo-Nazis.

“Following Trump’s win, posters plastered on telephone poles in Canadian cities invited ‘white people’ to visit alt-right websites. Neo-Nazis spray-painted swastikas on a mosque, a synagogue and a church with a black pastor.”

During this period, they go on to say, Canada witnessed its most deadly homegrown terrorist incident when Alexandre Bissonnette, a right-wing extremist, murdered six Muslim men at an Islamic cultural center in Quebec City.

In their view, there was a shift to the right in Canada before the Trump presidency, starting with the election of Stephen Harper of the Conservative Party as prime minister. “These years were also marked by militarism, a retreat from human rights, an elimination of hate speech protections, fear-mongering and hate, anti-immigrant rhetoric, and restrictions on immigrants and refugees to Canada. Especially pronounced was Harper’s vilification of Muslims.”

On balance, Right-wing Extremism in Canada is a useful addition to the pantheon of academic works about the radical right-wing scene in this country. It might have had a broader readership had the authors written their book in a popular rather than in a top-heavy style. Be that as it may, it contributes to a better understanding of this generally neglected subject.